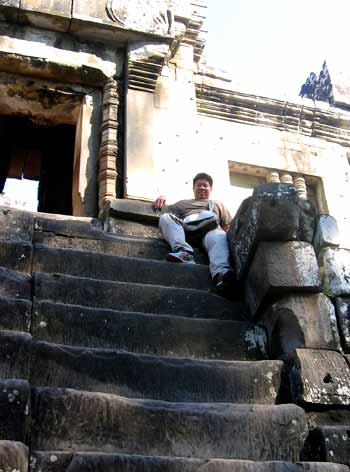

The steep steps with tall risers and shallow treads at Ta Keo, Angkor, Cambodia. Photos by Casual Chin and Sarin Va

Simon Crilley, designer and author of the Future Thinking blog, left a very interesting comment on the recent ‘Architecture & Security‘ post:

“These architectures of control aren’t new: temples in India and Morocco have gateways with lintels so low that people must dip or bow to enter the temple, just in case they weren’t intending to respect their gods.”

This made me remember reading about the ‘intentionally’ steep steps with very shallow treads used to approach some temples – the idea also being to compel visitors to bow their heads (in this case, to watch their steps very carefully for their own safety) and arrive in a state of some deference (if not reverence) as well as relief after a long climb. The above pictures show the very steep steps at Ta Keo, Angkor, described here:

“Next, I climb Ta Keo and start to notice that my upper legs are not really in any shape to climb 45 meters of stairs, where every step is a foot and a half high and only 4 inches deep (on the “easy” west-side). Supposedly they build them this way to ensure you bow your head. Well, in my case I have to do it using both my hands and feet, as vertigo really kicks in at some point (and that does not really happen easily).”

Of course, in both cases (low lintels and steep steps) the enforced ‘reverence’ is often only the appearance of reverence, but think about this: does increased blood flow to the head (from lowering it) cause significant temporary physiological changes? Does bowing your head (e.g. when praying) cause you to become more (or perhaps less) alert? Does it, perhaps, put you in a suggestible state? Or does it give you a feeling of peace or fulfilment which is then associated with the environment in which you experience it?

There’s been plenty of research on brain function during prayer and meditation, so I’m sure this question must have been addressed by someone (I just don’t know enough about the field to know where to look). For example, the image to the left (from Hothouse Bikram Yoga) shows a yoga posture claimed to “increase blood flow to the brain bringing mental clarity, good memory.” Does regular ritual prostrated prayer (e.g. salat) lead to actual changes in the brain in the longer term? Perhaps, in the temple examples, it’s the sudden light-headedness that may accompany raising one’s head after the prolonged period of increased blood flow into the brain, which gives the ‘intended’ effect.

There’s been plenty of research on brain function during prayer and meditation, so I’m sure this question must have been addressed by someone (I just don’t know enough about the field to know where to look). For example, the image to the left (from Hothouse Bikram Yoga) shows a yoga posture claimed to “increase blood flow to the brain bringing mental clarity, good memory.” Does regular ritual prostrated prayer (e.g. salat) lead to actual changes in the brain in the longer term? Perhaps, in the temple examples, it’s the sudden light-headedness that may accompany raising one’s head after the prolonged period of increased blood flow into the brain, which gives the ‘intended’ effect.

Are any readers better able to comment on this?