This is the first in a series of essays where I’ll try to look at some of the realities of working freelance in this field; I hope these will be interesting and possibly useful to others contemplating this kind of work. Please note, these are only my own musings and ramblings, written mostly on train journeys across North London, and I might look back on them with embarrassment and disagreement.

At the moment, I’m a freelance designer/engineer/maker. What that means is hard to define. There are no obvious boundaries: I’ve said ‘Yes’ to almost every project, mostly out of necessity but partly out of trying to determine what I’m any good at. In practice that means that in the last year-and-a-bit I’ve worked on some diverse stuff, from developing ultra-lightweight bikes to designing novelty packaging, from researching multinationals’ brand architectures to doing toothed belt calculations for gearboxes. I’ve tested radio-controlled things in the Thames looking across at Windsor Castle, and grappled with CSS while sitting in an abandoned factory in Dalston. I’ve hand-lettered sandwich shop menu blackboards and sprayed T-shirts with the logo of a new telemetry spin-out company. There’s mechanical engineering in there, some graphics, some electronics, prototype building, even copywriting.

What it’s shown me is that a jack-of-all-trades is not necessarily master of none, but unlikely to be any more than master of some, few in fact. And the main reasons for that — so far as I can tell — are time and money.

Time

If every project is different, you pretty much have to start by spending time simply finding out what you’re doing, what the precedents are in that field, what important things you need to know, even what equipment you’ll need to do the job properly. Some clients tend to assume that anyone ‘technical’ can fix (or indeed design) absolutely anything involving engineering materials, electronics, computers, etc, and while to some extent I don’t think that’s untrue, given experience, it’s probably not the best policy always to say ‘I’ll give it a go’. But you do need to test your limits before you can know them.

Back to the point: if you have to spend a significant amount of time on each project learning about the field, each project is going to take you longer than it would for someone who already knows what’s what. And you will make mistakes, of course.

Money

What the above implies is that, as it’s going to take you longer, you’re going to have to work out how to charge. Should the client pay for your learning process? How fair is that?

One point of view would say that no, you’ve created an (intangible) asset for yourself, and the client should only pay for your time once you know what you’re doing. The other point of view says that acquisition of knowledge is a prerequisite of being able to deliver what the client wants. Just as you charge for the acquisition of materials, so should you charge for the acquisition of knowledge. I think the answer probably lies somewhere in between, but it’s difficult for a freelance person — reliant on a sporadic income anyway — to ‘write off’ days as ‘knowledge acquisition’. If you have zero income (and maybe some expenditure) for those days, then you’re going to have to budget for that somehow, and that’s something that’s difficult to plan.

A second major point regarding money is that, well, the client wants to spend as little as possible. Why has he/she/it employed you, a freelance individual with (probably) few facilities other than your brain and your hands, rather than a ‘proper’ design consultancy? Unless the client genuinely thinks you are wonderful, or are likely to come up with stunning insights or innovation which someone else wouldn’t, the reason is probably because you’re cheap, or the client thinks you’ll be cheap (‘Because you’re young, and have lower overheads, right?’).

Wexelblat’s Scheduling Algorithm

But — the client also wants you to be good. So you have to be good and cheap. And on a smaller budget, and with less expertise and experience to call on than an established consultancy. How are you going to do it?

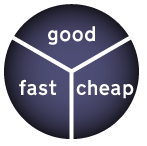

When I was working for a couple of weeks at a well-known design consultancy in London, two experienced freelance designers, David Baird and Simon May were also working on (more important aspects of) the same project. One morning, one of them (I can’t remember if it was David or Simon) drew out on his sketchpad, this diagram…

…and said ‘You can have 2 out of 3. It’s either good and fast (and not cheap), good and cheap (and not fast) or fast and cheap (and not good). That’s what I try to tell clients.’

This stuck with me at the back of my mind; I’ve since found out it’s (sometimes) attributed as Wexelblat’s Scheduling Algorithm (presumably after Richard Wexelblat?), though also apparently an ‘old designer’s adage’ (Jason Kottke) and an ‘old Hollywood maxim‘. The impossible triangle used to illustrate it here is cleverer than what I’ve drawn above, but the principle is the same. (As with so many principles and maxims popularised through software development, it also seems to apply very well to design and physical product development.)

As we’ve seen, the client wants a project to be good and cheap. Hence, if Wexelblat is true, it’ll be slow, even if some of that slowness is accounted for by knowledge acquisition, and mistakes. But if you’re charging for that time, you’re incurring costs in the process, which tends to counter the ‘cheap’ aspect of the project. So, there’s an inherent difficulty with applying Wexelblat to jobs with a significant learning curve. If your costs are proportional to the time you spend, you can’t be cheap without also being fast, and bad (since you possibly don’t even know what you’re doing). For the inexperienced, cheap and fast and bad is possible, but good implies not fast and not so cheap unless — as we considered earlier — you’re willing/able to write off your learning time.

Reality

If the above sounds negative, I don’t mean it to. It’s exciting working on new things and building up expertise, but when clients’ primary reason for choosing you in the first place may be cheapness, you’re going to have something of a difficult compromise and balancing act on your hands, just in terms of scheduling your work and budget, let alone the specific challenges of the project in question. It might mean that your definition of ‘1 day’s work’ slowly seeps into becoming ‘7.30 am to 2 am’ just in order to get everything done in the same number of days you promised, and for the same cost. That’s fun for a while, but gets pretty tiring for those around you even before you get fed up.

An implication of all that is that to be competing on price alone can be a stressful game, especially when having to do so simply to get enough work means that you have a lot of learning to do for every project. It’s something of a positive feedback loop, a vicious circle. But, if you can build up enough experience in a particular field, and are able to use knowledge acquired (or problems solved) on a previous project, you have the start of something more edifying. You may still be able to compete on price, but you can now be cheap, faster and better, since you know what you’re doing. And, slowly, gradually, you might even be able to specialise in a certain field, no longer jack-of-all-trades, but actually mastering something.

Pingback: designswarm thoughts » Blog Archive » links for 2007-03-12

Pingback: What I’ve learned so far as a freelance designer/engineer/maker: Part 2 at fulminate // Architectures of Control