In Materializing the Invisible, we considered invisible and intangible phenomena—the systems, constructs, relationships, infrastructures, backends and other entities, physical and conceptual, which comprise or influence much of our experience of, and interaction with, environments both physical and digital. ‘The invisible’ here is potentially everything from how the building’s heating system works, to the algorithms behind targeted ads, to who’s friends with whom, to where corruption is occurring in government, to where your IoT fridge sends the data it collects, to people’s mental imagery of time, to the electricity use of devices, to networks of cameras and sensors, to how political decisions are made. It also potentially includes things that happen at scales or in dimensions we can’t directly comprehend, from planetary processes such as climate, to the interaction of electromagnetic fields, to the microscopic. And things that happen, that enable day-to-day functioning of our lives, but we don’t know much about. Where does our food come from? Where does our waste water go? What route did that package take to get to us?

The process of revealing the invisible can improve understanding, help people explore their own thinking and relationships with these complex concepts, highlight problems, power structures and inequalities, reveal hidden truths, connect people better to the world around them, and enable people to act. It is not necessarily about visualizing the invisible—it can be about making it audible, tangible, smellable, or otherwise experienceable: we explored techniques from fields including data visualization, sonification, data physicalization, ubiquitous computing, tangible interaction, analog computing, qualitative displays, and the study of synaesthesia to create ways to materialize these invisible phenomena.

More details, including background reading, in the syllabus.

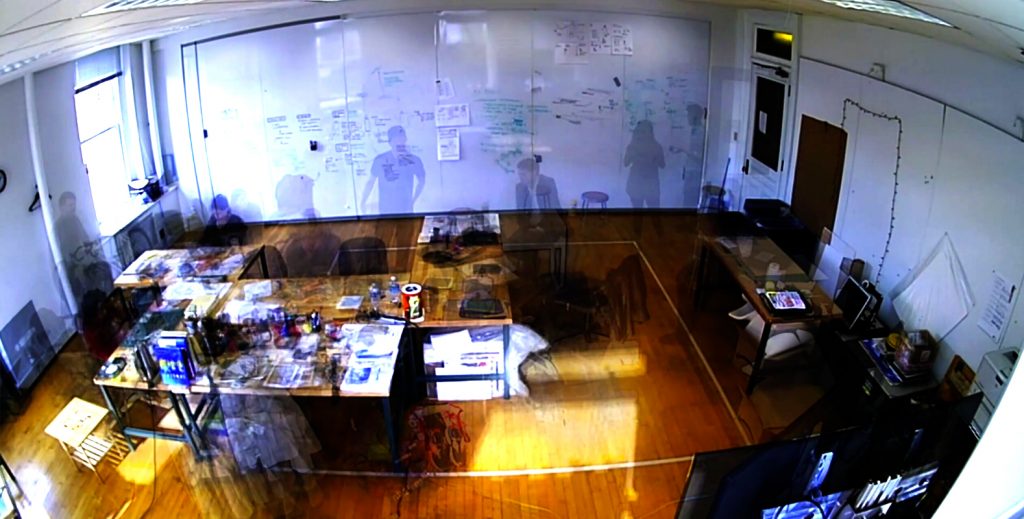

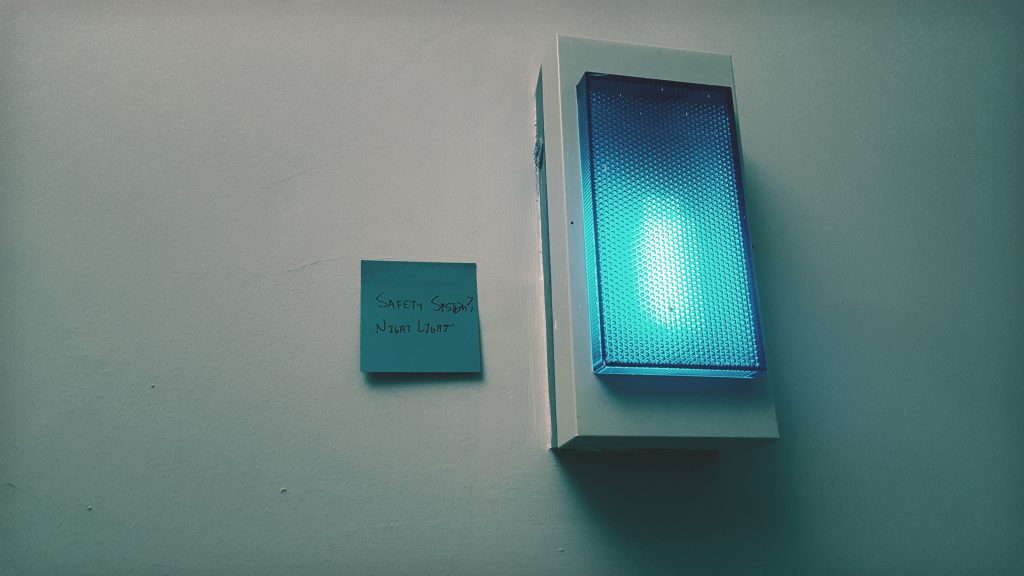

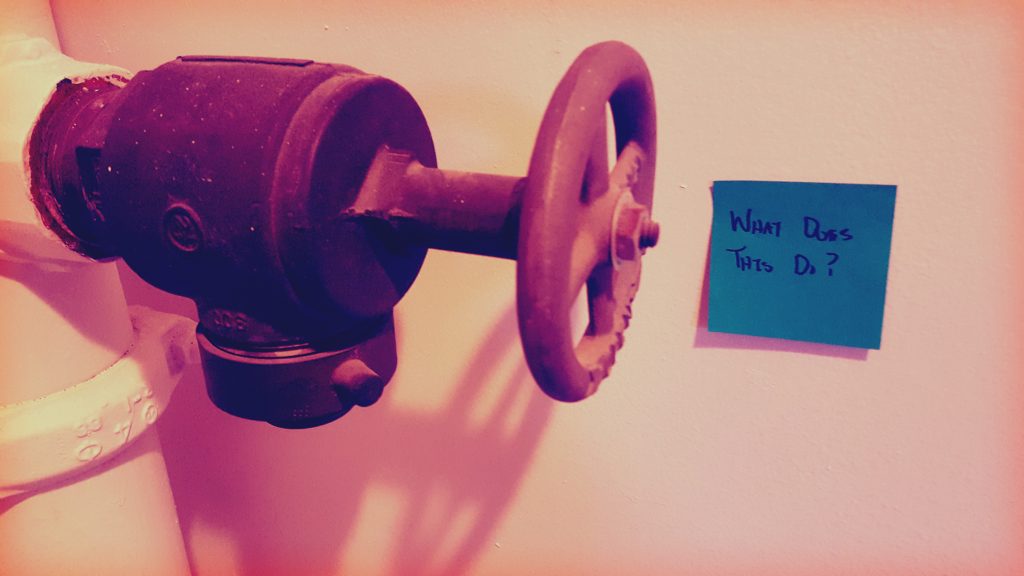

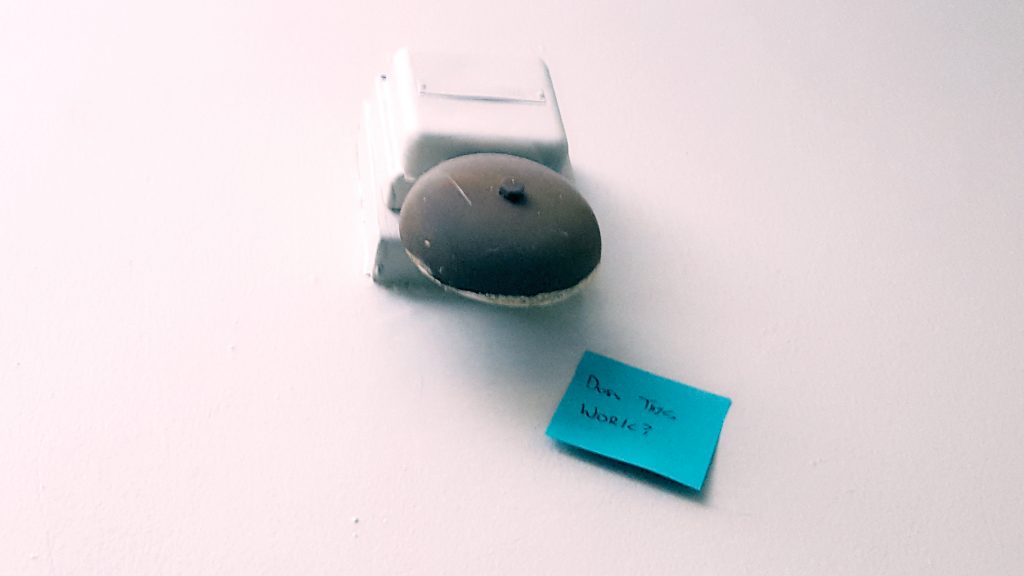

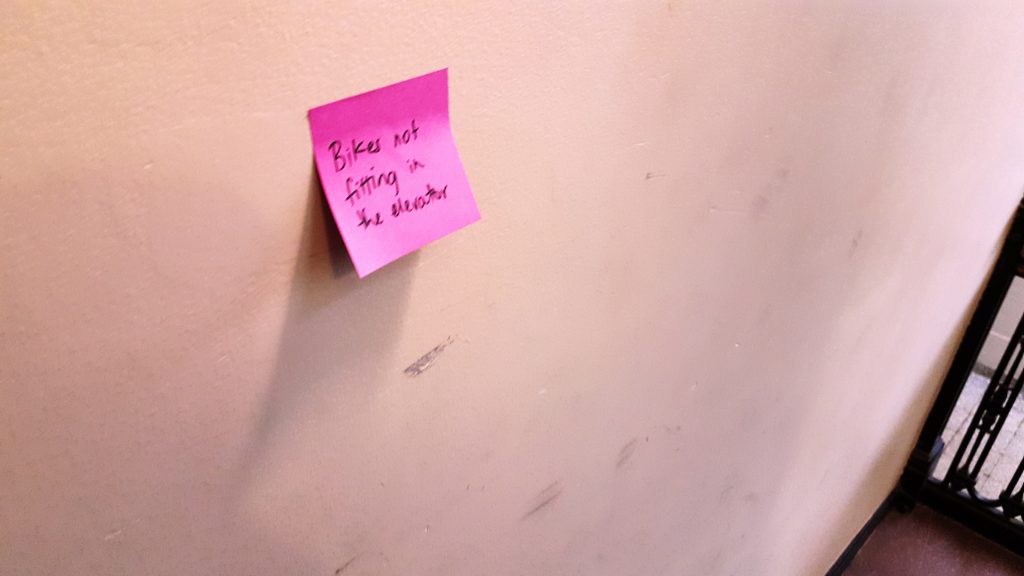

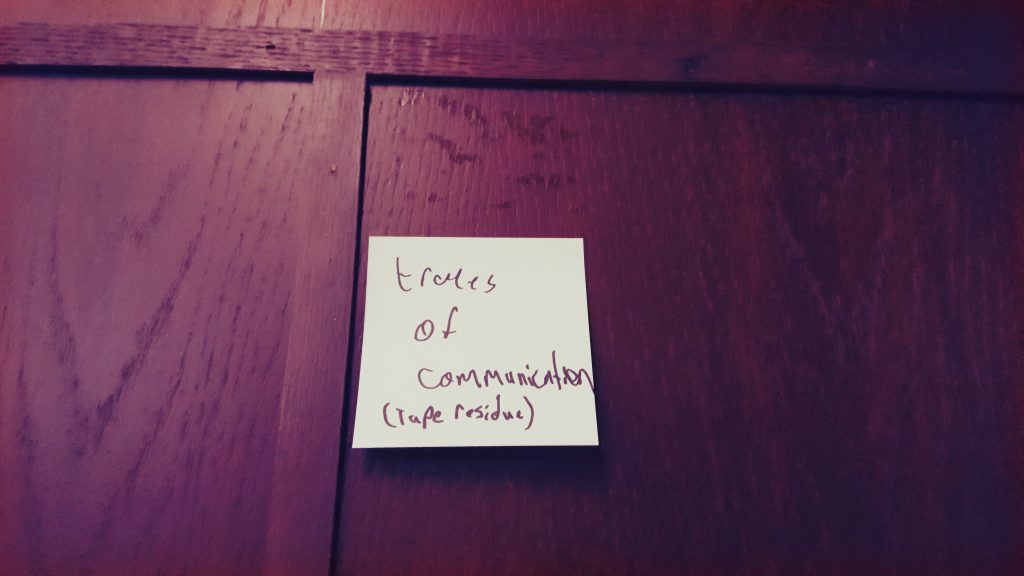

As a starting exercise we examined some ‘invisible’ and unknown things within the building itself (Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall), noting questions and ideas with Post-It notes in situ. These ranged from questions about who has access to certain rooms or controls, to what some of the controls are in the first place. There were also traces of action and use—patterns which might be invisible in the sense of not being paid attention to, but nevertheless present in the use of the building.

The class project was to choose a phenomenon which is ‘invisible’ within a physical, digital or hybrid environment, find a way of getting access to it, and design and build / make / create a way of materializing the phenomenon, making it accessible to people more widely. As a group we brainstormed different phenomena which might be investigable, and possible forms of representation.

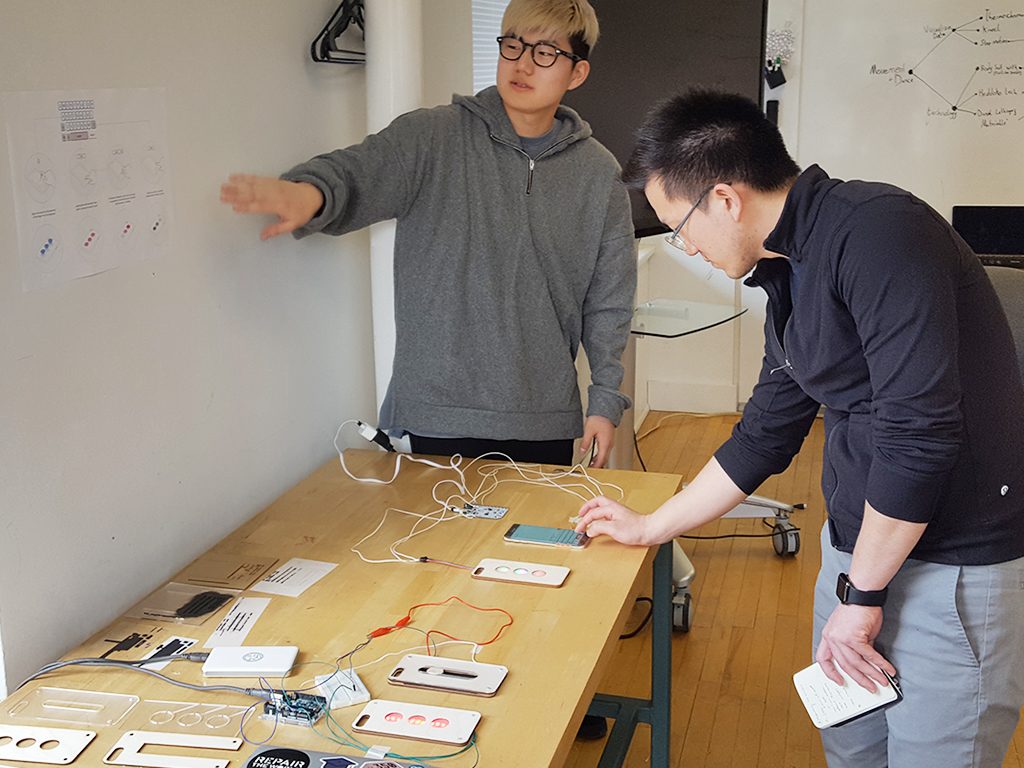

Ji Tae Kim’s project Whitespace looked at the invisible aspects of communication in text messaging, following on from his previous project Fear of Missing Out. Whitespace explores ways to materialize and express “rich contextual and verbal cues” through “an intuitive extension to instant messaging”. Working prototypes used copper tracks, Bare Conductive ink and Touch Board, and Arduino.

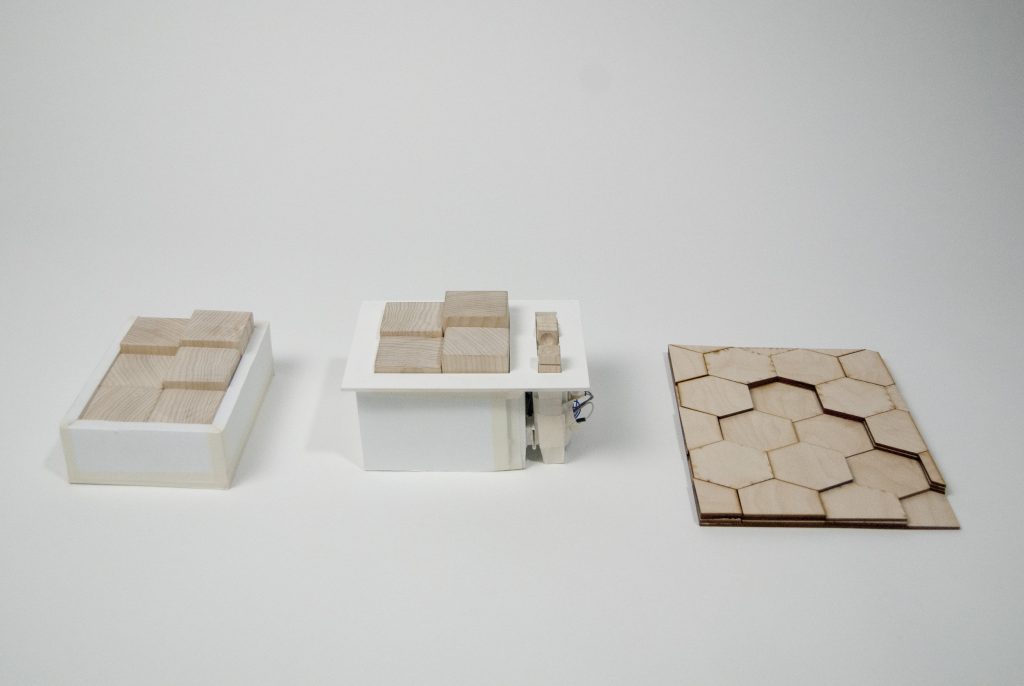

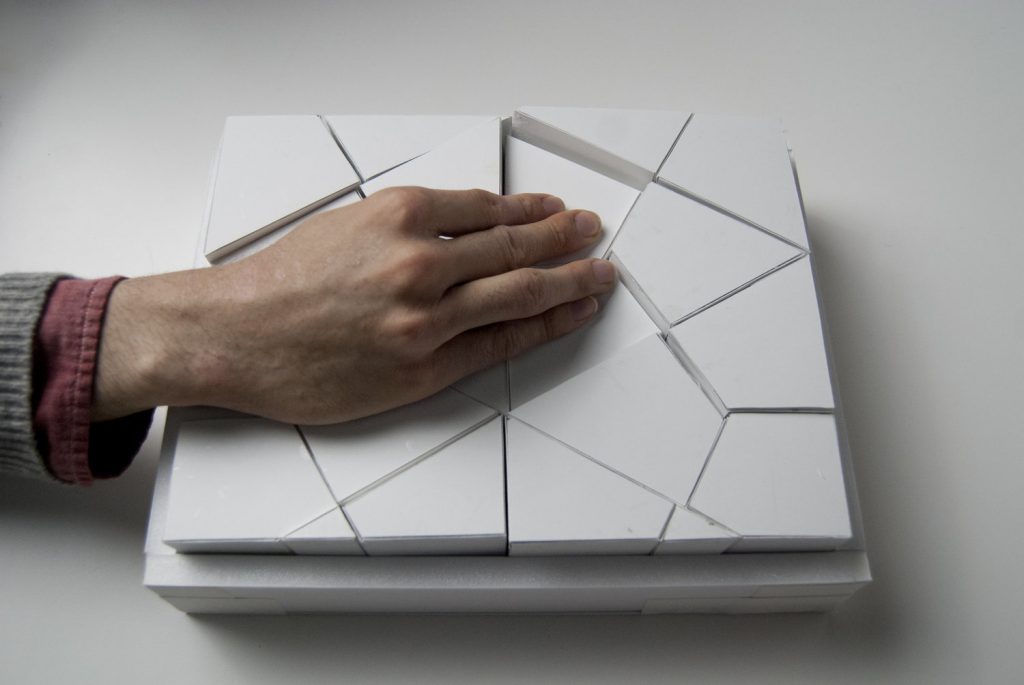

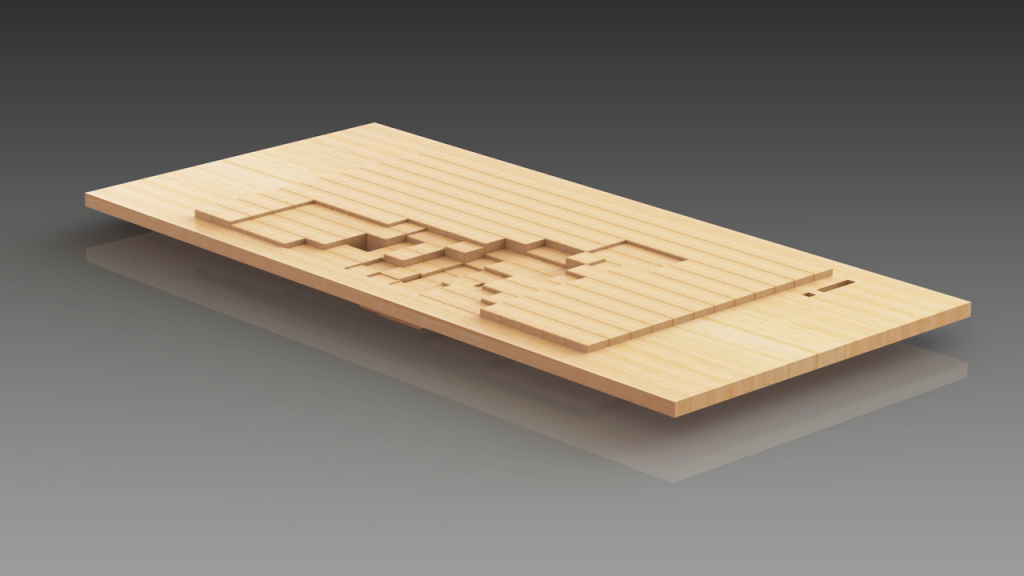

Jasper Tom and Chris Perry‘s project Kairos examined “an invisible phenomenon ingrained in everyday life”: the passage of time in a space, specifically around working at a desk. The question “Where did the time go?” and the idea of desk legacy, the patterns of use left by a previous user of the desk in a shared workspace, informed by analysis of timelapse video of the studio, came together with inspirations such as Daniel Rozin’s Wooden Mirror, MIT Tangible Media Group projects such as Daniel Leithinger’s work, and Tempurpedic foam, to create a desk surface which could ‘play back’ the patterns of how it had been used, via an interface using wooden blocks. A working prototype of part of the surface used Arduino and servo motors to demonstrate the effect.

One interesting aspect discussed during Jasper and Chris’s presentation was how while evidence of physical work is often obvious in space, such as a painter’s palette, the evidence of digital work is often invisible—a slightly worn keyboard, perhaps, but little else.

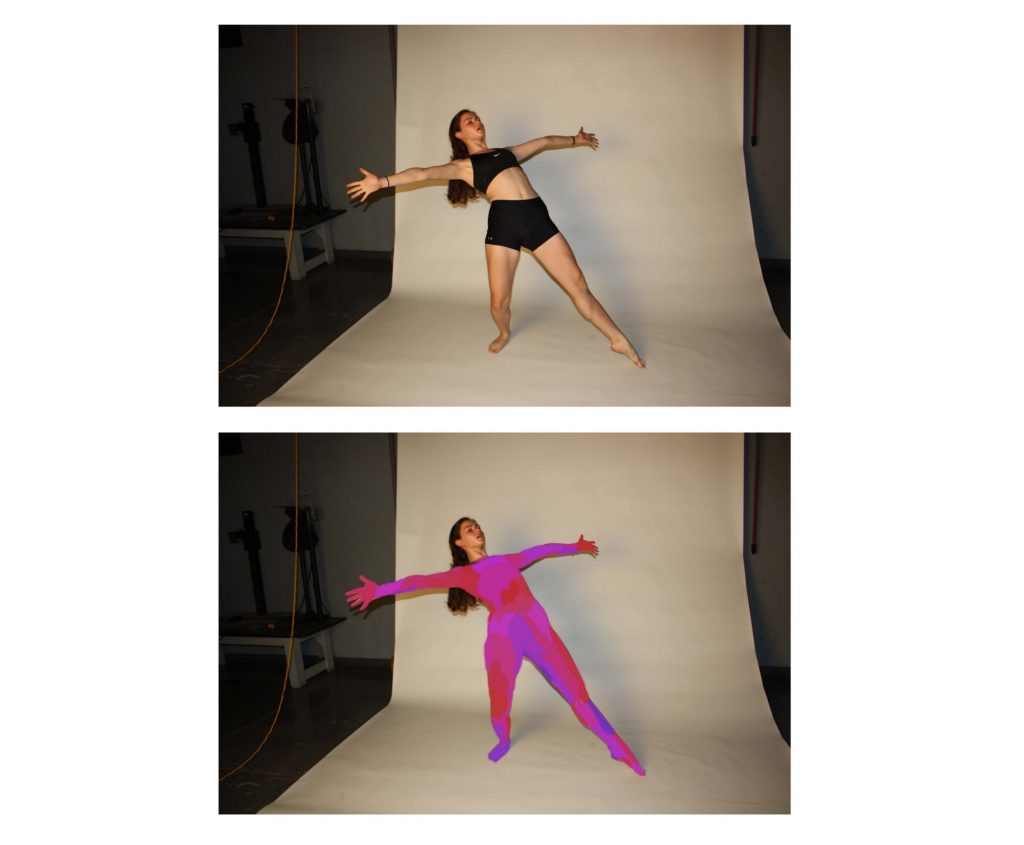

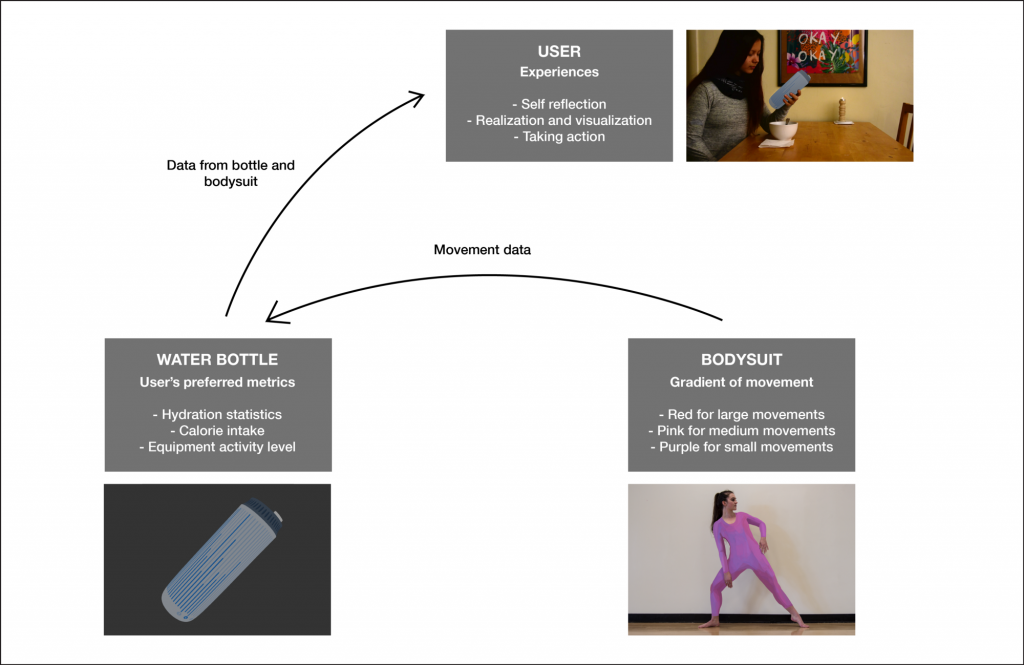

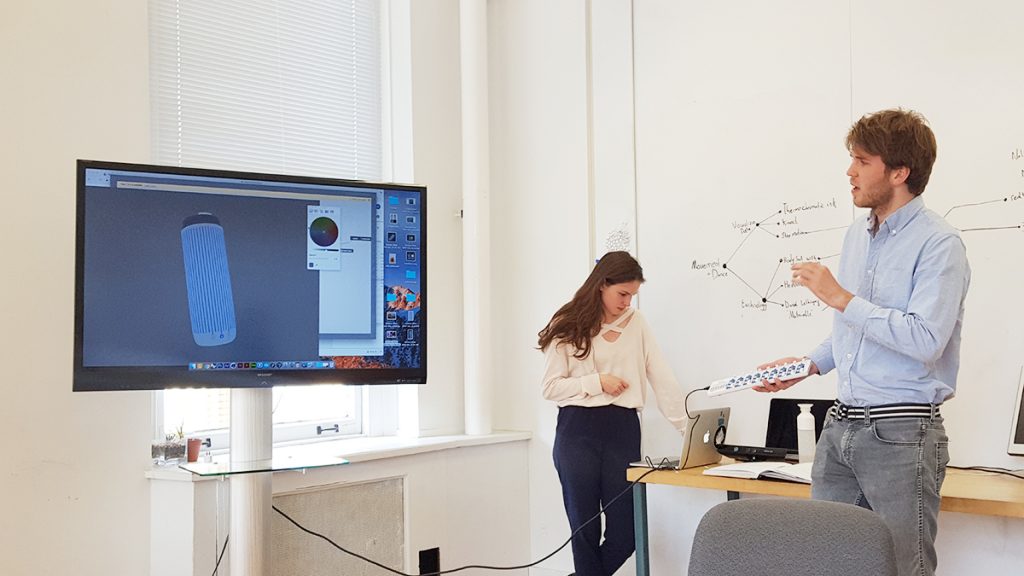

Gilly Johnson and Ty Van de Zande worked together to explore aspects of human movement (dance and exercise), and the related issues of hydration and focus. Focus + Movement proposed a color-changing bodysuit which could work together as part of a system with a water bottle, both to make the invisible patterns visible, and to enable reflection. Gilly and Ty captured movement by dancers using a Kinect, connected to Max MSP, and then simulated the body suit via After Effects.