In part 1 of ‘What I’ve learned so far…’ I looked mostly at being a ‘jack-of-all-trades’ and the idea of ‘Wexelblat’s scheduling algorithm’ (or the ‘good, fast, cheap: pick two’ theory) as it applies to a young freelancer starting out. There were some very insightful comments which are also well worth reading.

Before starting on Part 2, I feel I should apologise for the relative dearth of posts recently. This seems to be a recurring pattern, although this time it’s actually resulting in some people unsubscribing in Bloglines… The reason is primarily that I’ve had a series of projects which have taken a lot out of me, time-, sanity- and confidence-wise. I can’t really explain too much at this point, but referring to Client Breeds 6, 7, 8 and 11 as explained at the excellent FreelanceSwitch should give some hints! Suffice to say, I hope never to make the same series of mistakes again. A later part of this series will be my own take on the ‘Client Breeds’ idea and managing different clients’ expectations, but for the moment, on with Part 2:

The Portfolio Dip

When you’re at university, college, or working on design in your spare time, the rate at which you add new work to your portfolio can be equal to the rate you do the work. If you do three projects in the final year of your degree, you can add three projects. But when you start doing ‘real’ projects for companies, they’re likely to be confidential, at least until they reach production (if they even go this far), so you can’t show anyone. This applies, of course, to designers working full-time for a company as well as freelancers, but is more importnat for freelancers. (Incidentally, a friend of mine whom I’d classify as an extremely successful freelancer, suggests that only 1 out 10 potential products developed for clients are ever likely to reach mass production, and he makes that clear to the clients as he goes, which is something I’ve been far too reticent about doing.)

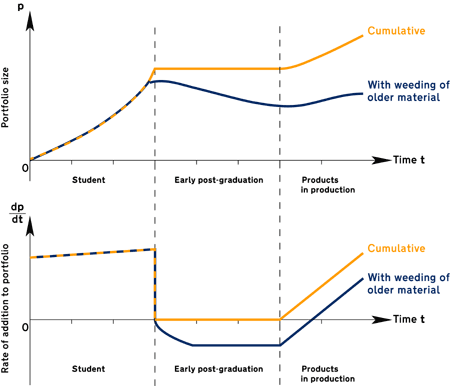

Back to the point: the confidentiality requirements mean that – superficially at least – your portfolio starts to look a bit stale (e.g. this). The rate of new work added drops sharply, and this can certainly have an effect on your own confidence quite apart from – we might expect – not being so persuasive to potential clients. (If you’re also, sensibly, weeding out some of the older projects of which you’re not quite so proud – too studenty, too weak – then as well as the size of the portfolio decreasing, the period it covers may also decrease to a narrow focus around, say, the final two years of your degree. And the rate of work added actually goes negative.) Roughly, you might end up with something like this:

If the most recent stuff you can show them is a student project, or even a speculative competition entry hacked together in your spare time (if any), then they may well treat you like a student or a speculative chancer rather than a professional designer. What they expect to pay you could also be in accordance with this.

Equally, even if the early freelance jobs you take on do reach production quickly, or can be shown without a confidentiality worry, they’re not necessarily going to be especially impressive. For example, I’m grateful for getting the job of making new signage (below) for a local sandwich shop, to the client’s design, but putting this into a portfolio primarily focusing on more technically innovative work may well dilute its appeal to certain prospective clients.

All of the above reinforces something very important. Industrial experience during a degree – ideally a summer internship or an actual sandwich year placement – can be extremely valuable, especially if some of what you worked on has reached production by the time you graduate or start your freelance career. In effect, this work can help ‘plug’ the portfolio gap, with real-life, commercially viable products which may even be familiar to potential clients already. While choosing a sandwich course makes your degree longer – and that year’s wages may be very low – with the right choice of company and some hard work, you may have an asset which makes your portfolio work stand out above others’.