Amidst an already-existing polycrisis, the world’s an even more fragile and scary place right now, largely thanks to the seizure of power in the US by wannabe fascists, and their willing enablers. We can see exactly who would have stood next to the bully in the playground.1 Is obeying in advance a kind of prefigurative dystopian experiential future? Sadly we’re all going to find out without having opted into the experiment, starting with people already marginalised by society, from trans folk to migrants, but also essentially anyone making the world better, from peace campaigners to air traffic controllers to aid workers to vaccine experts to climate scientists. And, it seems, in time, an attempted dismantling of much of US academia—destroying or compromising Columbia, Penn, the University of Maine system, Fulbright Scholarships, the NIH, NSF, all of it, and seizing students right off the streets.2

Introducing the Institute for Sustainable Worlds

Against this ominous “1933” backdrop, last month I started what is in many ways a dream job: developing and directing the new Institute for Sustainable Worlds at Norwich University of the Arts. We are a brand-new initiative, a research studio at a specialist creative arts university in a mediaeval city in the east of England—a lively and bustling little university that has excellent teaching and knowledge exchange with its communities, very impressive facilities (and technical staff), and growing research activity and ambitions. It is a welcoming place that really does feel qualitatively different to anywhere I have worked before, and I feel extremely lucky to have this opportunity.3 (I should make it clear: this post does not necessarily represent the views of my employer.)

But what is the Institute for Sustainable Worlds going to do? And is that different when our world is being assaulted so dramatically, systems being ruined by the cruel and venal and violent? Should it be different when much of UK higher education itself is in crisis and contraction, and the UK more widely is in such a painful state of inequality? How do we relate to an academic world that really has not even begun to process how the world is changing? What responsibilities does (a small part of) a creative civic university have, locally, but also globally? Can the university be a platform for doing things in the world? Can the Institute for Sustainable Worlds be an actor, in this space—using its privilege to do things differently, usefully? How can we embody social benefit, social justice, in what we do, and how we work? There are lots of centres and groups and institutes that do amazing work academically but remain in the university bubble (I have been guilty of that too) because it’s just so much work even to do that—to maintain a pipeline of funding and projects and publications to meet the endless expectations of the treadmill (some tired metaphors here—if only we had a way to generate new ones)—let alone seriously work with society.

A few years ago, when Twitter still existed, I did a couple of threads exploring the idea of a university as a platform for doing things, and I’m taking that as one tentative starting-point for the Institute for Sustainable Worlds. A university is an organised group of intrinsically motivated (and in Norwich’s case, also very creative) people and resources, with (in theory) no motive for extractive profit (mostly). It’s a machine (in good and bad ways) with facilities and equipment and infrastructure and clever people who want to take part in things, and it has huge amounts of knowledge and expertise in its people—knowledge and expertise that is available to bring to bear on problems. If you want to make change in the world through generating (or applying) knowledge, you could see a university as a kind of incubator, a place where the sustenance to allow that to happen is provided in a warm, safe, structured environment where the goal is not primarily profit generation, but knowledge generation (in Norwich’s case, through creative practice, although not exclusively). How many types of societal institutions are able, permitted even, to prioritise knowledge generation rather than appeasing shareholders and their lobbyists? We don’t have many.

However, many universities end up very focused on themselves—about preserving their own systems and the economic systems they’re in, and so cannot be radical platforms for change—for doing things in the world—because they are too entangled in the system. But it doesn’t have to be like this. I think it’s possible—indeed urgent, given what we’re facing—for a different form of organisation to emerge, that addresses problems in the world, in context, with students learning through actually working on them, a critical co-investigation model. Maybe it seems clearer to me as a designer because the question of practically doing something (albeit often in an under-theorised way) is never far from my mind—but it would need to be interdisciplinary to be useful. Tao-Leigh Goffe argues for “the necessity of interdisciplinary methods for our collective global survival beyond the climate crisis”. Collaborations between arts, sciences, social sciences, humanities, and technologies—beyond arts being used only instrumentally—could have a powerful role in how our societies can imagine and dream what ‘sustainable’ futures might entail in everyday life. From my experience working with the pioneering Centre for Unusual Collaborations in the Netherlands, I have seen the value of how approaches, often creative or playful methods, from ‘outside’ particular disciplines, can enable groups to understand each other better, from understanding different worldviews to developing collaborative future projects together.

Imagination infrastructuring

Now, I know how constraining a pure “design” framing can be when this is really about creative (research) methods, and the multiple roles they can play in sustainability, Norwich, both university and city. But also, as April Soetarman so succinctly reminds us, you can do anything but not everything. The Institute for Sustainable Worlds could be a centre for sustainability in the arts, or a centre for sustainable design, but both of these are huge topics and there are excellent groups already doing this. The name is also important: ‘sustainability’ as a concept has plenty of limitations, as many people have explored, but my current thinking is that that discussion itself is a useful one to have, as part of what we do. What are we aiming to sustain—and what are we not?

I think we need to focus on a particular way of approaching the intersection of sustainability and creative research methods, and the angle that makes most sense to me is imagination, and how it relates to our collective futures. We’re trapped because we can’t imagine alternatives to our current trajectory. The “crisis of imagination” that Amitav Ghosh, Geoff Mulgan, Ruha Benjamin, and others have identified is something that critically-informed creative methods are well-placed to address. They can surface cultural assumptions about futures and what worlds people assume to be desirable or possible. They can materialise aspects of diverse (and divergent) possible futures in engaging and experiential ways—enabling provocation, confrontation, emotion, and reflection, including on (contested) pasts and presents and people’s lived experiences. But they can also open up collective imagination for more sustainable worlds—building capacity and confidence to imagine, visualise, and experiment with different futures and more just societies, beyond dominant imaginaries, and with new interactions between humans, nature, and technologies. We can use storytelling and speculative design to bring imagined futures to life experientially, even prefiguring new ways to live—all the while valuing plurality and avoiding a singular ‘prediction’ model—but we can also work on developing methods and tools and techniques and opportunities for others to do so: futures literacy (in the confidently reading/writing/critiquing sense) and imagination literacy more widely. (I’d really like to explore how the Institute can work with Norwich as a UNESCO City of Literature in this context: this is a City of Stories after all.)

The Worlds part of ‘Sustainable Worlds’ could be very powerful—there is an inherent valuing of plurality (or even pluriversality) and what multiple futures can co-exist, but also a recognition that applying creative methods to understanding people’s own worlds, their lived experiences, their imaginaries, hopes, and fears, nostalgia, is just as important as society-level visions. (Norwich’s work around mental health and arts fits well here, I think). I’ve spent the past decade or more trying to explore imaginaries (in one form or another) through design methods, and while some of that has been aligned more with imaginaries of technologies—e.g. spookiness, or qualities, or alternative ways of thinking about AI or robots—much of it has really been around ways for people to share and materialise aspects of their own worlds, from students’ mental health to how we imagine energy, and I see this as part of a continuum with imagining and enacting different futures, since those futures are never created in isolation.

We can see the Institute for Sustainable Worlds as aligned with the imagination infrastructures and collective imagination movement (as discussed by Cassie Robinson, Olivia Oldham, Keri Facer, Ruth Potts, Joost Vervoort, Roy Bendor, and others, and supported by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation), or the amazing work that people such as Phoebe Tickell, Amahara Spence, and Rob Hopkins are doing. Ruha Benjamin makes an interesting argument that imagination itself is infrastructure. In general I think of what we do as imagination infrastructuring, inspired by Chris Le Dantec and Carl DiSalvo’s interpretation of infrastructuring through design as “creating socio-technical resources that intentionally enable adoption and appropriation beyond the initial scope of the design”. Developing creative methods to help people share their worlds, is a form of imagination infrastructuring that works in people’s current worlds as much as futures.

And so, although this is a research institute, knowledge exchange via public engagement, events (both in Norwich and elsewhere), collaborations with organisations inside and outside of the university system, and ultimately short courses, are all part of what we can do. I hope through this engagement, we can also develop and prefigure new models for how a university research group can be and act in the world. Alternative models for education and research in related areas such as Black Mountains College, the Hawkwood Centre for Future Thinking, School for Poetic Computation, School of Critical Design, Transition Design Institute, School of Systems Change, School of International Futures, School of Good Services, Urban Futures Studio, School of Machines, Making, and Make-Believe, Monstrous Futurities, Future Observatory, Dark Laboratory, CLEAR, National Centre for Writing, Centre for Sociodigital Futures, Center for Science & the Imagination, Lab4Living, the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, Monash Futures Hub, the Planetary Civics Inquiry (Dark Matter Labs + RMIT + RISD + others) and many more, with varying degrees of embedding within or outside of a ‘conventional’ academic or university structure, are inspirational in different ways. What can we do that benefits from being part of a (quite unconventional) university, but with open doors?

I very much welcome ideas to expand and reshape this list, but some crucial areas where I think we need these imagination infrastructuring methods include aspects of climate adaptation (our physical environment, our relationships with nature and living in changing landscapes, social practices and culture, energy, resources, transport), climate justice, communities and their futures, human and planetary health and wellbeing, new economic models in an era of degrowth and post-growth, just transitions, co-design, policy development, and our relationships with technologies. We can’t do all of it, although many of these topics are deeply interconnected anyway. But we also need these kinds of methods for teams’ own processes, for supporting new ways to think and approach complex systems creatively, regardless of topic. One of the main insights from seeing how people have used the New Metaphors cards over the past few years (and to some extent with Unbox) is just how people have found applications that are really about building capacity to think differently, rather than directly creating new metaphors to use instrumentally.

Building this together

Some of this imagination capacity is more about our own lives and how we think about them, while some is about societal or even global scales. How can we do work which builds on Norwich and East Anglia’s context—a rural area, already one of the most vulnerable in the UK to climate change, with world-leading research centres on climate, food, and so on—and links it with ideas and knowledge and communities elsewhere, including my own adopted home of the Netherlands (which has much shared history with the east of England) but also around the world? How do we ensure that work towards better worlds is not done in isolation?

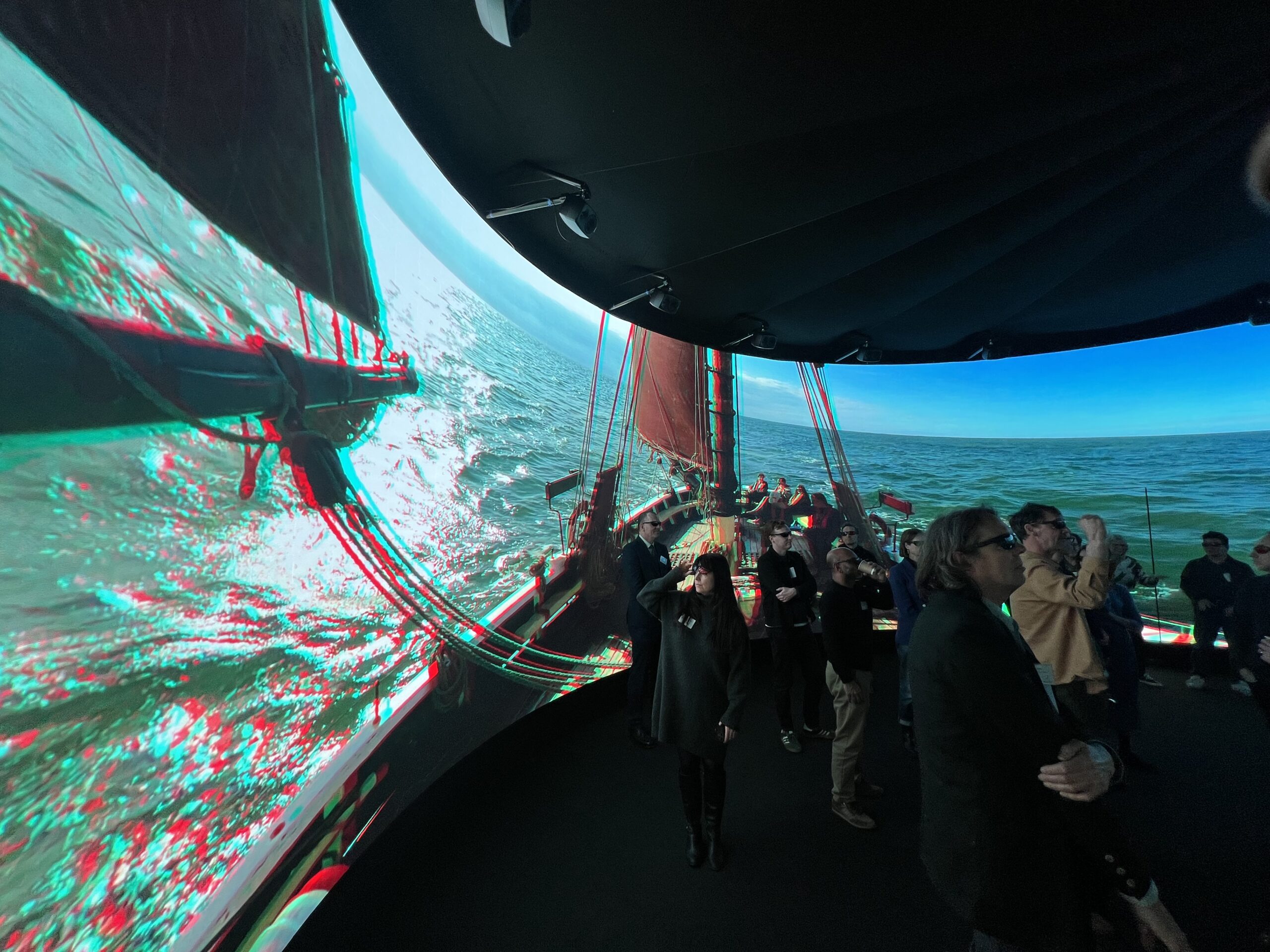

If you think you might be interested in collaborating with us, please do get in touch (d.lockton@norwichuni.ac.uk). This is a collaborative effort, and I wouldn’t dare to presume that we could do this alone. While I want us to do some of the work of building the Institute for Sustainable Worlds “out loud”—to share our thinking as we go along, and connect with people who are doing allied work 4—developing the Institute is also going to be about inviting people into the process more actively. I’m inspired by the excited / intrigued / curious questions I’ve had from everyone I’ve met so far at Norwich, about what exactly the Institute is going to do, but also by ideas and hope in some great talks by (and with) visitors to Norwich over the past few weeks, including Saskia van Stein, Annabel Howland, Peter Cook, and glimpses of new perspectives from exhibitions such as the amazing Can the Seas Survive Us? at UEA’s Sainsbury Centre (curated by Ken Paranada) and Arieh Frosh and Ed Compson’s fusion of Doggerland and offshore wind energy at the East Gallery. We have a (slightly) more established sibling at Norwich, the Institute for Creative Technologies and the very impressive Immersive Visualisation and Simulation Lab (below) which offer some intriguing possibilities for experiences and new forms of engagement.

The building in Norwich where the Institute will be based is at Bank Plain, the former Barclays Bank just down from the castle and opposite Anglia Television (home of Tales of the Unexpected). But the other end of the building marks the start of London Street, the first pedestrianised street in the UK (in the sense of: a former through road which was closed to motor traffic) and in some ways that enactment of a different kind of future, nearly 60 years ago, also gives me hope.

Future blog posts / newsletters will explore specific aspects of developing the Institute for Sustainable Worlds, including ways to get involved, specific topics and areas of focus, thinking through our links with Europe and further afield, and how to build a community. And keep an eye out: we will (I hope) be advertising a couple of jobs in the coming months.

Notes

1. And sadly it seems like many university presidents in the US—a more powerful position than a UK vice-chancellor or Dutch rector—are, so far at least, largely content to comply and keep schtum in the hope that the bullies don’t pick on them next (even though they already are, as the Columbia example). I remember, when I worked at an American university, the linguistic contortions around academic freedom, and essentially “maybe some crumbs will fall from Trump’s table”, that the senior management used to defend giving a Trump crony a sinecure in the face of a massive petition from students and staff. Too much of the framing so far is about losing overheads, essentially, rather than destroying society, or what’s actually right or wrong. American academia and scholarship is being bulldozed: NIH, NSF, even Fulbright Scholarships smashed by a group of fascists, and I don’t hear anywhere near enough in UK (or Dutch) academic discussions about the longer-term effects of this on the world, given American dominance in so many areas. (back)

2. The systems that have kept us, privileged people among the societies of the global north, largely safe, are, we are quickly realising, apparently “designed to let the very worst people rise, designed not only to allow them to rise but to prefer that people such as this will rise” as A.R. Moxon puts it, echoing a Stafford Beer-esque ‘the purpose of a system is what it does’ argument. Of course the systemic dimension of all of this is not news to those who have highlighted over and over again systemic injustices, particularly racism and sexism. But it seems as though the system’s output of chaos and hate has moved up to an even more dangerous level. I’m not sure that the systemic design community—wonderful as they are—has really reckoned with this kind of issue yet. (back)

3. For myself: for the first time in my academic career—which if I date it from the start of my PhD, in 2007, is 18 years, which seems like a lifetime away—I feel as though “proving myself” means something else now. If I look at it more clearly, I have spent 18 years seeking approval/validation really, as so many of us do in academia. The idea of endlessly striving to get yet another paper out or taking on more admin because that’s what you “should” do if you want the tenure/promotion committee to see you as a valid person, seems quite misguided in retrospect, when all many of us really want is to be trusted to try out some ideas, and not infantilised. My hope is now that writing those papers is because they are intrinsically interesting, and useful to the community, and ultimately to society, not because it’s what the system demands just to stand still. At least, that’s the mindset I hope I can adopt. It feels like (with grateful thanks to everyone who has helped and supported me along the way) I have emerged from climbing a tangled path up a hill, through a bank of fog, covered in burdocks and nettle stings, and finding that there’s a mysterious valley ahead, down below, with a shaft of sunlight through the clouds. It’s clear that mental landscapes needs some additional metaphors! (back)

4. I am so often inspired by organisations and people who do this well, for example Louise Armstrong’s recent post about building the Decelerator and while I think the speed of our work might not quite yet suit the weeknote format (maybe in time it will!) I do want to share some regular updates. As I noted back in December, there was a period when I used to blog regularly, and write, and share things, and put tools and ideas out there for people to use. The last few years, though, I realise that I’ve disappeared, somewhat. I’d retreated into a much more narrowly bounded academic institutional cattle-crush, in which aspirations and ideas are redirected into serving a system which demands certain things. I didn’t blog much any more because putting ideas out there like I used to do made me feel vulnerable, risky within a career where everything hinges on what people think of you, and where judging and assessing people (whether students or staff) is, for some, the whole point.

I wrote a draft of a long post about this—academia as duck decoy—(among other topics) in 2022 and then never published it, because it came across as too negative even for me, but one of the parts which I feel is important to get out, was this—partly because my new job does not share these characteristics, and yet so much of academia seems to:

“When the system replaces your goals with its goals, it does so gradually, until you look back on a week (one of less than 2000 | have left in my life, if I’m lucky) and think, well, what did I do this week? I pasted my signature into some forms and assigned quantified figures to students’ work using a standardised rubric I played no part in developing. I excitedly read something inspiring that someone somewhere else has being doing, and wished I had the motivation and time and opportunity to do something similar, if only I could get out of the burnout room. It will be the same next week. It seems like the academic system so often only values you, if that’s the right word, for as long as you are a reliable, interchangeable component; some variants might allow “doing you own thing” In your own time, but it seems rare for them to support you doing it—if anything it’s seen as an eccentricity. A huge part of the appeal of academia for me—and I know for others—is exactly the freedom to explore, to think, with other motivated and curious people. It is appealing! Or at least, this imagined version of it is.”

But: I miss blogging, and thinking out loud. And I think this new job is different. I feel ambitious and excited and want to share ideas with people! (back)