Carnegie Mellon School of Design, Senior Design Labs, Fall 2016, 51—401

- Final projects: see cmuplaylab.com

- Discussion of the final projects

- Updated: December 21, 2016: Please note: this syllabus has been updated over the semester and rewritten into a kind of ‘review’ of what happened.

- Play Lab took place Mondays & Wednesdays, 1.30—4.20pm, MM 213/4; Session 1: August 29—September 28; Session 2: October 3—November 2; Session 3: November 7—December 7, 2016

Dan Lockton, Assistant Professor, Margaret Morrison Carnegie Hall 207b; danlockton@cmu.edu

Introduction

Seniors (4th-year undergraduates) in Industrial and Product Design at Carnegie Mellon take three ‘Senior Design Labs’, Wonder Lab, Speak Lab, and Play Lab, each of which aims to help students develop some ‘design agility’. They set out to enable students to integrate and revisit skills they’ve developed through their time at CMU, but applying them in new and different situations. The idea is that this helps graduating students develop a shift in perspective on their own abilities and identities as designers, and gives them confidence to tackle new kinds of problems and challenges in a reflective way, through knowing themselves better.

Play Lab 2016 was specifically about exploring ambiguity. Over five weeks, the 33 students worked on the idea of future(s), and designers’ role in both creating (in a sense), and responding to, ideas of possible futures that by definition, don’t exist yet. It’s about developing and being able to show a thought process which is not just about problem-solving, but comfortable with ambiguity, problem-finding, and problem-worrying.

Our starting points for exploration were three quotes: most famously, as phrased by the novelist William Gibson, that “the future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed” (there are different versions of this quote going back to the early 1990s); Jenny Holzer’s “You live the surprise results of old plans” and “A good science fiction story should be able to predict not the automobile but the traffic jam”, attributed to Frederik Pohl. The basic idea is powerful from a design point of view: what ‘futures’ do we see emerging right now, what might they grow into, what consequences could they have, and how would designers be involved? What power, or agency, do designers even have here? Through a series of small exercises, students build toward designing and creating ‘pockets of the future’ that can be glimpsed or experienced by others.

Course objectives

By the end of the course:

- Comfortable discomfort: you should be comfortable—well, as comfortable as you can be—with applying the design skills you have developed over your time at CMU, to inherently ambiguous questions about the future.

2. Problem-worrying: you should have carried out a project through which you don’t ‘solve’ a problem, but rather, ‘worry’ at the questions involved, creatively exploring possibilities and opportunities through synthesizing your design and research skills, thinking through ‘making’.

3. Reflective designing: you should be confident in using the project to demonstrate your ability to engage creatively to explore ambiguous futures, with a critical eye on your own role as a designer in shaping and responding to trends.

Course outline

The course overall comprised five exercises, starting with small challenges around observation and speculation, and building to a bigger project in the final two weeks of the five-week session. The classes were a mixture of group discussion, presentations, demonstrations and one-to-one advising in the studio. Students kept a blog as part of the course, which was part of the assessment; these could be made public or kept private depending on students’ preferences. As students come from different design specialisms, it was expected that they will use whatever physical or digital media suit their skills and confidence. The fuzzy edges of ‘the future’ permit a deliberate fuzziness in the resolution of the work: ambiguity was encouraged.

Details of assessment, learning outcomes, etc are in the syllabus intro PDF.

It’s worth noting that Play Lab took place in three groups over the semester, and the details of what we focused on with each group differed slightly as questions and ideas and issues arose. With the final group, the presidential election results occurred on the morning of one of the classes, and provided an emotional and quite difficult atmosphere to our discussions of the future. Questions around filter bubbles, fake news (a form of design fiction, surely), blurred boundaries between truth and falsehood, and changing geopolitics ended up influencing a number of the projects. Oddly, many of the themes from J.G. Ballard’s ‘The Future of the Future’, written for Vogue in 1977, also seemed to recur, unprompted, throughout the class.

Some references, precedents and inspirations

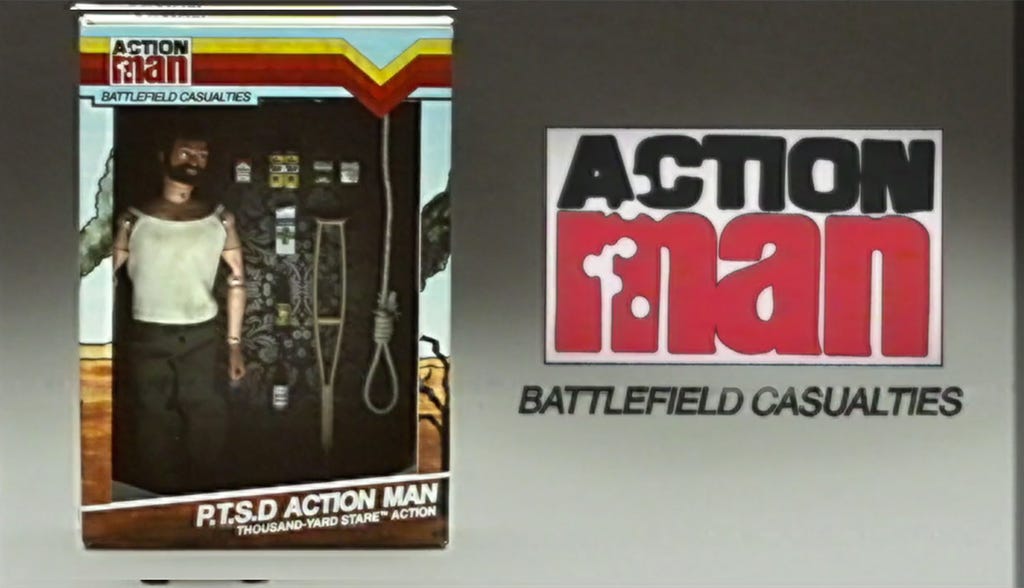

There are many interesting and very talented people working in different areas of design, futures, speculative design and design fictions of various kinds. Over the weeks with different groups, we looked at and discussed a number of projects and tools from people and groups including: Dunne and Raby; Superflux; Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagan; Near Future Laboratory; Strange Telemetry; Extrapolation Factory; Natalie Jeremijenko; Interaction Research Studio at Goldsmiths; The Onion; Changeist; The Yes Men; Anne Galloway; Iohanna Nicenboim; Vytas Jankauskas; Luiza Prado and Pedro Oliveira, Luke Sturgeon; Keiichi Matsuda; James Auger and Julian Hanna; Matthew Buchholz; Simon Stålenhag; Jakub Różalski; Benjamin Bratton; James Bridle; Simone Rebaudengo; Loove Broms; Veronica Ranner; Daisy Ginsberg; Timo Arnall; Sputniko, Warren Ellis; Darren Cullen; Bruce Sterling, Charlie Brooker; Alison Jackson and others. (I also wanted to show them Scarfolk and the Framley Examiner, but I think the Britishness might have just been too confusing.)

Some of the work we looked at which I think had a particularly large influence on some students’ projects includes the following:

Play Lab also took place in the context of ongoing debate at Carnegie Mellon around issues of speculative and critical design, including the Climactic: Post Normal Design exhibition curated by Deepa Butoliya, Ahmed Ansari, and Katherine Moline, Deepa Butoliya’s elective class Speculative (Post) Critical Design and Peter Scupelli’s class Dexign Futures, and was fortunate to coincide with visits to CMU by people working in related areas, including Anne Burdick, Bruce Tharp, and Maria Lamadrid. We also had the legacy of Aisling Kelliher’s work at CMU including a previous class on Design Fiction and Imaginary Futures, and previous iterations of Play Lab with a speculative design focus.

While Play Lab 2016 was not explicitly focused on speculative and critical design (Deepa Butoliya’s class gave her students a proper grounding in that), much of what students produced was nevertheless approaching this area. It was, at least, using design to provoke discussion, particularly in relation to the future mundane, as Nick Foster has called it. If the ideas and scenarios the students created ended up telling us more about today’s preoccupations and concerns, from the perspective of North American undergraduate design students, than being politically motivated calls to action, that is little different to the majority of work on design fictions, and no worse for it. As we will see with the projects themselves, the broad themes give us an insight into what worries, inspires, and preoccupies a group of talented designers about to go out into the uncertain world of 2017.

I was influenced in putting aspects of the class together by many strands of thought, including an exercise that Veronica Ranner and I developed for a session called ‘Plans and Speculated Actions’ at the Design Research Society 2016 conference earlier this summer, with Molly Wright Steenson, Gyorgyi Galik and Tobie Kerridge; doing a talk for Tobias Revell and Ben Stopher’s SCD Summer School at the London College of Communication; a gathering of design-and-futures people organised by Georgina Voss, Justin Pickard and Tobias Revell in 2015; and taking part in the 2014 Oxford Futures Forum (thanks to Lucy Kimbell).

Exercise 1: Observing possible micro-futures

We started by looking at William Gibson’s famous statement (variously phrased)Â that:

“the future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed”

and thinking about how this idea is manifested in practice. What do we see around us—things, actions, habits—that are potentially ‘from’ a future? What do we perceive to be anachronisms, in ‘both’ directions (past-in-the-present and ‘future’-in-the-present)? What is the ‘texture’ of the present? What things come and go, and what stay? Can we tell which ways of doing things are going to become ‘normal’ or popular, the seeds of possible futures, and which won’t? How does this differ across cultures, across countries, but also within one place? As designers, are our observations and thinking here different compared with what people with different agendas and skills might pay attention to?

Looking specifically at the ‘distribution’ of ‘futures’ in the present and in the past, we discussed three ‘time traveler’ memes—the time-traveling hipster (see image at the top of this blog), and two women apparently using what look like cellphones—to modern eyes, at least—in a 1928 Charlie Chaplin movie and a 1938 clip of a Dupont factory.

We considered how we ‘read’ modern behaviors into images from the past, and how that relates to what we assume, as designers, about the way people ‘will’ use things that we design. Looking around the room for examples, we saw things such as the projector propped up on a diary, a trash can being used to hold the door open and the first aid kit box being used as a noticeboard, all of which are not necessarily what the designers intended, but nevertheless are almost second nature to us. (See Jane Fulton Suri’s Thoughtless Acts, Uta Brandes and Michael Erlhoff’s Non-Intentional Design and Richard Wentworth’s beautiful Making Do and Getting By for much more of this kind of thing).

In considering the role of the designer in both creating and responding to ‘futures’, we thought about Pagan Kennedy’s comment, in her review of Gibson’s Distrust That Particular Flavor, in which she said:

“Cars lumbered past like ponderous elephants of rusty steel, not so different from the cars of 30 years ago, and seemed not to belong in the same world as the tattooed kid punching code into his laptop nearby.

Under the spell of this book, I suddenly understood my surroundings not as a discrete contemporary tableau but as a hodgepodge of 1910, 1980, 2011 and 2020.”

We also considered how this kind of ‘hodgepodge’ could mean that, in a sense, we are all living in different worlds, a flaky, uneven present– what is ‘new behavior’ or ‘a new way of doing things’ for one person may be something quite mundane for someone else. (This theme came up later in a number of the projects showing the point of transition from one way of doing things to another—when some people have adopted a new way, and others haven’t.)

We talked about futures, and forecasting, including this 99% Invisible podcast on trend hunters (and creators) WGSN and Stylus, a brief look at retrofuturism, via Matt Novak’s Paleofuture blog and the illustrations of Bruce McCall, before thinking through the ideas in Donald Rumsfeld’s ‘Unknown Unknowns’ speech, and how they relate to ideas of technological progress and effects on society and the environment:

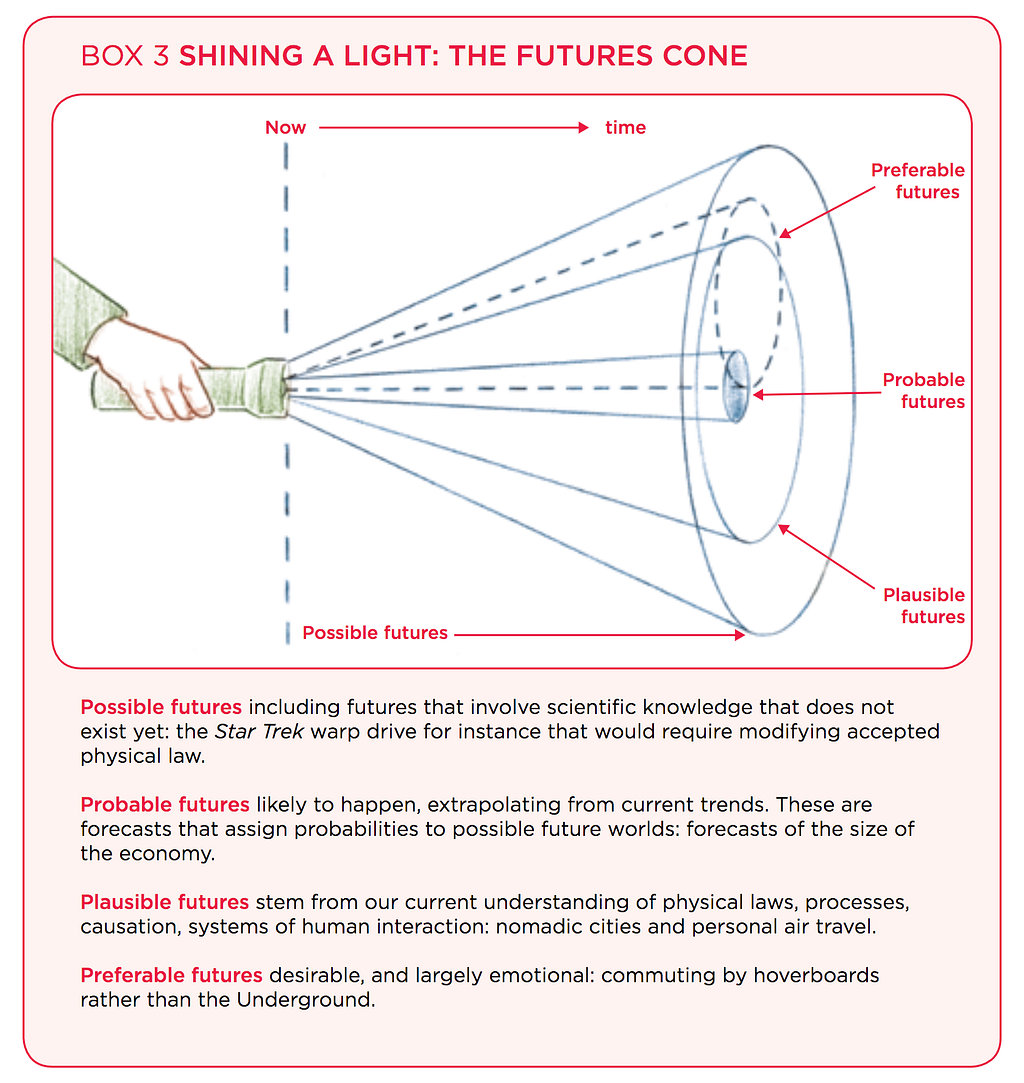

We also talked through Voros’s futures cone, as explored by people such as Stuart Candy (see pages 42/43 of the PDF) and Jessica Bland and Stian Westlake (see image)—and featured in Chapter 1 of Dunne & Raby’s Speculative Everything, one of the readings (see below)—and what it might mean for designers plotting a career trajectory. Futures that might once have been merely ‘possible’, such as driverless cars, are rapidly moving right to the center of the ‘probable’ cone, while other futures recede in probability. What happens if you specialize in something that goes nowhere? And yet, as a designer, you are potentially partly responsible for the way in which the future develops. (Sjef van Gaalen has some thoughts about how the cone interacts with Rumsfeld’s unknown unknowns.) We also looked briefly at the idea of ‘backcasting’ from the right-hand side of the cone to the left (the present), discussed some of the deficiencies of treating the present as a ‘singular’ point, and asked what a cone extending backwards into multiple ‘pasts’ might look like. (Some of my own thoughts about how this potentially relates to Transition Design are here.)

Introducing the first exercise, we thought about how observation, and noticing things around you—objects, behaviors, trends, outliers, social ‘rules’ and norms, and ways of doing things (practices)—can be a valuable habit to get into as a designer, and how using this form of observation to try to see some of the ‘unevenness’ of the present could be a way of uncovering possible ‘micro-futures’ that might be the start of something. This is the idea of ‘weak signals’ as explained by Near Future Laboratory.

Was this man I saw at Helsinki airport in 2008, using a (for the time) startling, apparently enormous 20" HP laptop, with an external hinge, an early adopter of a trend that would soon be ubiquitous? Were we soon going to be seeing people using giant laptops in coffee shops everywhere? Was this a ‘pocket of the future’ in the present? Or was this an aberration? What about devices such as PDAs and personal organizers, which in some way seemed to presage today’s total cellphone saturation, and yet never reached those levels of popularity?

Jan Chipchase’s TED talk from 2007—nine years ago—on The Anthropology of Mobile Phones, describing his research fieldwork for Nokia, provides a fascinating ‘historical’ insight into how possible future(s) for cellphone use and communication practices were explored and envisaged through in-context research in a huge number of countries and cultures, and makes an interesting comparison with what actually happened in the subsequent decade. (Jan’s Future Perfect blog is an incredible chronicle / travelogue, and diving into the archives at any point is well worth it.) Exercises like asking people to empty their bags, to get insights into the minutiae of everyday life, can also be used to explore possible futures—what do you carry around that you expect to be doing so for the foreseeable future? What is temporary? What will change?

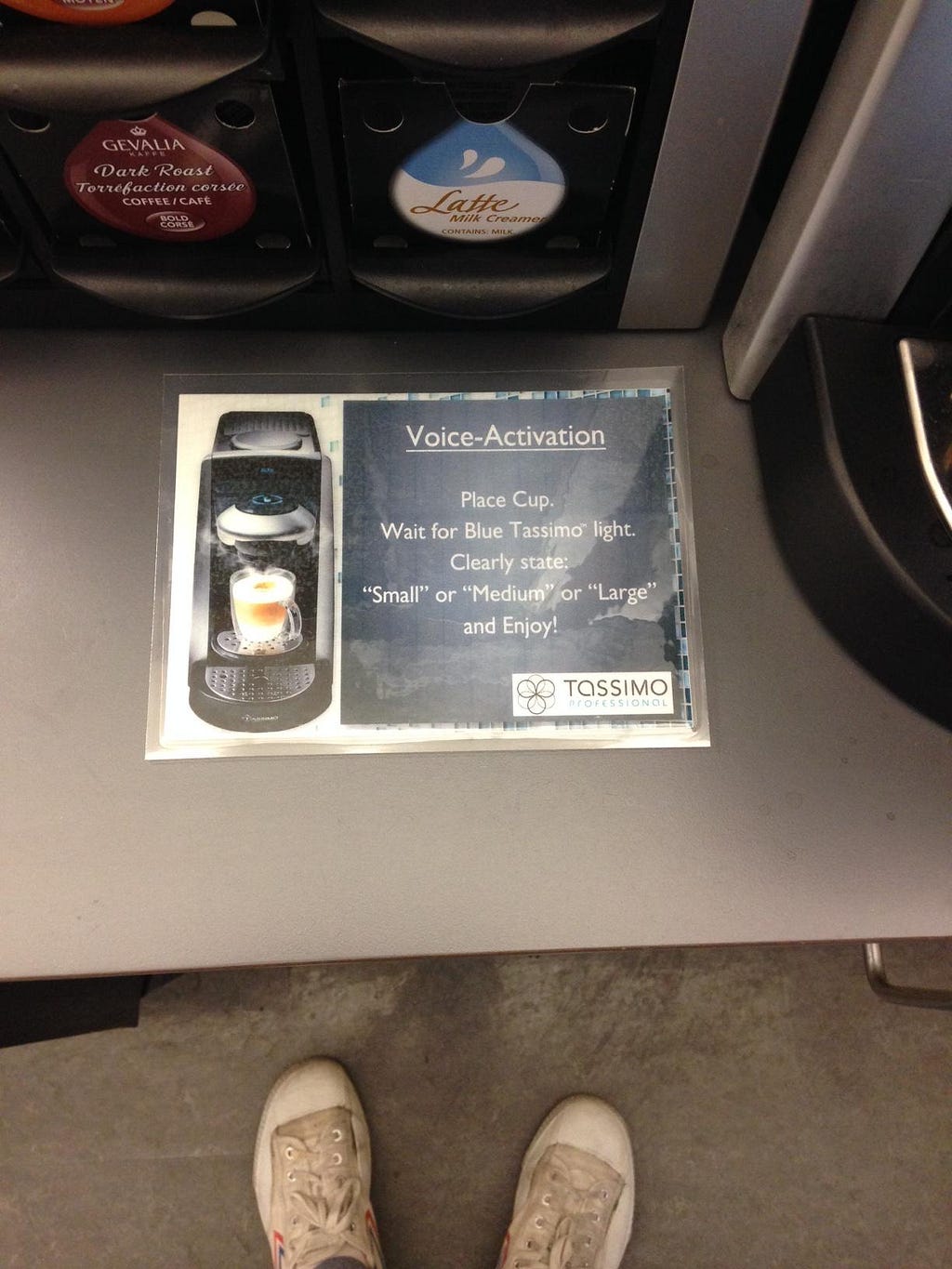

We finished the class by looking at a few examples, mostly collected online, of what might seem like ‘odd’ behaviors or outright misunderstandings , but which nevertheless maybe offer something interesting, the tantalizing seed of a different kind of system, where things work differently. Some involve adaptation, some ‘fighting back’ against a system (like make-up and fashion to prevent facial recognition), some involve people believing that something works in a particular way that it doesn’t really, but maybe it could.

Exercise 1

Look around you—on campus, online, anywhere—at the ways people are using things (not just technology, but clothes, fashions, mannerisms even). Notice unusual or intriguing sets of behaviors, and consider whether they could be possible ‘micro-futures’—small trends, kernels of the future in today, or maybe even today in the future.

They might be ways of doing things that seem culturally different, or age-specific. They might be things that just seem strange, or wrong. Or they might take a bit of noticing. Look at other people, but also perhaps yourself—what micro-futures might you be engaged in creating? Are there new habits you’ve developed, or you see yourself developing?

Document them somehow, using photos, video, screenshots, or even just your own notes (it’s not always easy to photograph people doing things!).

Ideally, find at least 3 possible micro-futures.

Readings for Exercise 1 (on Box, needs CMUÂ login)

- Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, 2013, ‘Beyond Radical Design?’, Chapter 1 of Speculative Everything.

- William Gibson, 1989, ‘Rocket Radio’, in Distrust That Particular Flavor.

Students’ blogs for Exercise 1 (non-public ones not listed)

Lauren Zemering: Cell phones and daily commute, Chairs as coat hangers, Social media and “auto-tagging”, Forgot your password?

Jiyoung Ahn: Minimalism, Sagging pants, Street art

Brandon Kirkley: (1, 2, 3) Green walls as aesthetic component in architecture, Fashion and wearable technology, Hyper-personalized targeted advertising

Albert Topdjian: Texting blindness, The path less traveled by / synthetic turf, The cool Velcro shoe

Kaitlin Wilkinson: Instant gratification, How Alexa / Amazon Echo might change the home, Social media creating a physical artifact of someone’s life

Jonathan Don Kim: (1, 2) Payment methods, Technology and change in the concept of centralized locations, Connections and the sense of ‘I’

Rachel Headrick: Sound effects that relate to everyone, Augmented GPS, Buy even your plants online!

Rachel Chang: Missing doorknob, Jill Magid turned Luis Barragán into a diamond: How do we represent ourselves after death?, Bots and AI in our daily lives

Diana Sun: (1, 2, 3) Share Closet / clothes-sharing, Interconnected world / smart water bottle, How driverless cars could lead to redefining ‘success’

Courtney Pozzi: Packaged Unpackaged Food, Makeup and societal norms, Hands-free (“Why are people always carrying stuff in their hands?”)

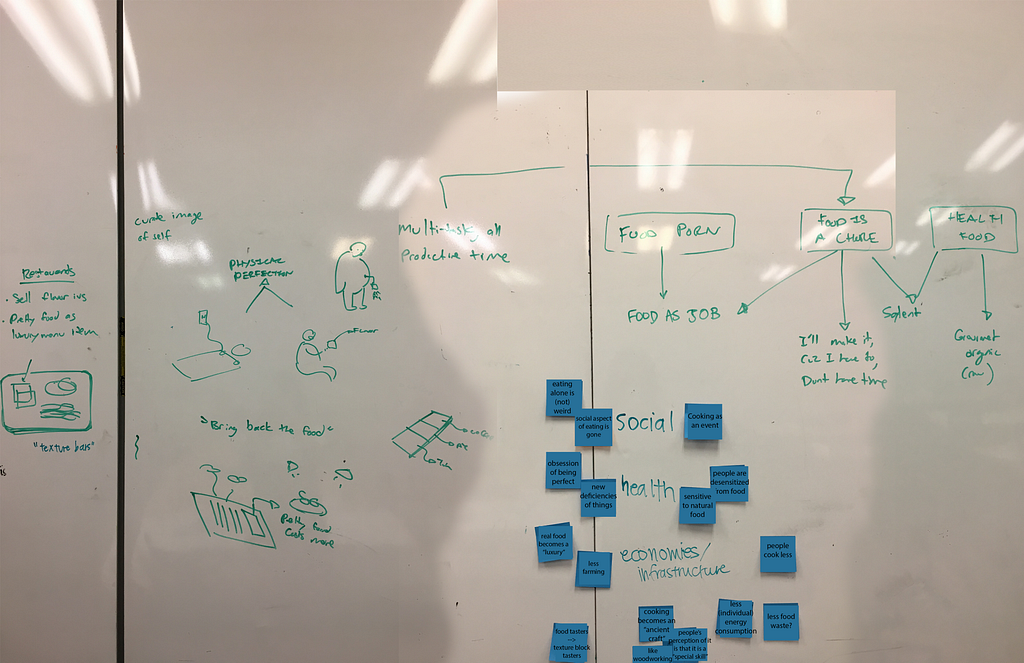

Praewa Suntiasvaraporn: Making everything automatic, Obsession with food, Sexualization of food, Food as a chore

Jillian Nelson: Railings as bike parking, Pocketbra, Phone as mirror, Holding papers inside of laptop, Backs of chairs as coat or bag storage, Roads / sidewalks as a billboard, Using a trashcan as a ladder to climb into window, I used a hammer to open up a beer bottle once, Kenny and the cereal bar

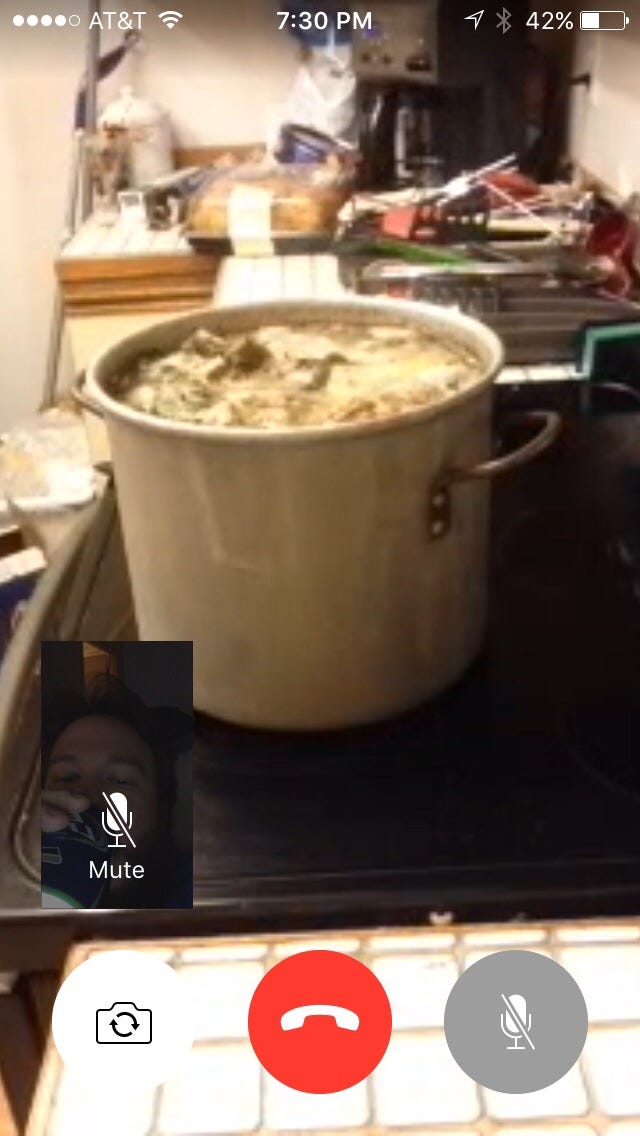

Leah Anton: People who brush their teeth in the shower, People who share their food over the internet, People who ask “How are you?” and mean it

Vicky Hwang: (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) Bidets and toilets, Hacking cables to strengthen them, Ways to open beer bottles, Skipping songs, Digital and seniority

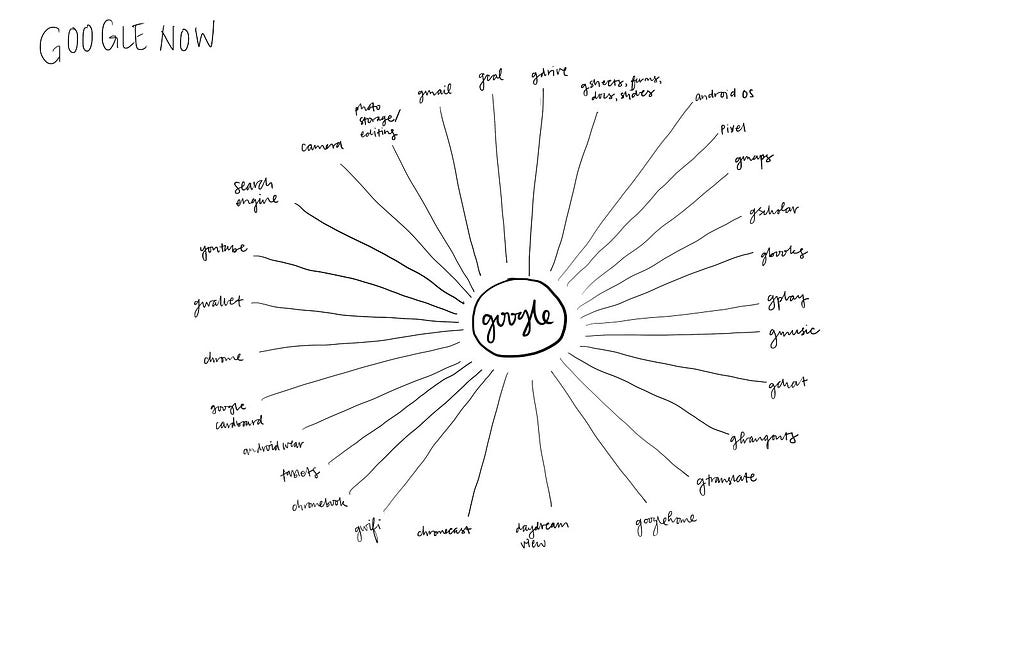

Jackie Kang: How-to videos, Social media/reality stars, Google

Zac Mau: Lifehacking, For Sale@CMU, Embedded OS

Brian Yang: Public transport in Asia, Toothpaste maximizer, Velcro spice rack, Food caddy

Catherine Zheng: Prescriptive lifestyles, Distracted walking and waiting, Cosmetic augmentation

Lea Cody: Status update, Health tracking, The American Death

Linna Griffin: Augmenting nature through tech, Citizen journalism, Temporary beauty technology

Gabriel Mitchell: What will augmented reality actually be like?, What will bots actually be like?, How much information is too much?

Temple Rea: VR Experiences, Transcranial direct stimulation, Facial Action Coding System, Inherent vs explicit form, Tools for creators, The relationship between technology and our feelings

Zai Aliyu: Emotions and intelligence in technology, Civil inattention, Ephemerality, Impression management

Kate Apostolou: The political reality show, Emotional expression through technology, Technology’s effect on spatial thinking

Kaleb Crawford: Live-streaming, live-chatting, and and the meta-memetic zeitgeist, A/B Testing, Rhetoric Analysis, Context Collapse, Self-Identity through Non-Identity: Social media presence for a post-ironic generation

Ruby He: Banter with robots, Packaged empathy, Moments relived

Alisa Le: Gender identity and gender expression, Sharing economy, Automating decisions and simplifying daily routine

Julia Wong: Flexible and mobile environments, Grunge, “nostalgia” and celebration of the “retro” / less perfect and “genuine”, Extended self

Jeff Houng: Tattoos and Body Self Expression, Biometric Data or Authentication, The Pursuit of Hyper-Efficient Wellness

Exercise 2: Side-effects and side-shows

‘You live the surprise results of old plans’: Jenny Holzer, Survival series, 1983—5

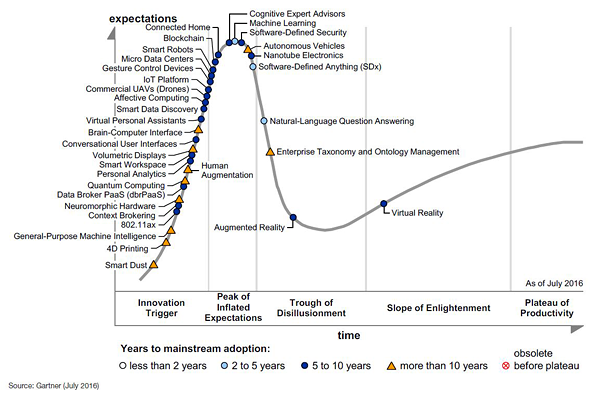

After discussing the micro-future trends spotted in Exercise 1, we looked briefly at some formal concepts and terminology in the theory of technology and innovation—Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations, from which common terms in design such as ‘early adopter’ come, Geoffrey Moore’s Technology Adoption Life Cycle (with its ‘chasm’ between early adopters and the early majority), and the Gartner Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies with its evocative terminology, especially peak of inflated expectations and trough of disillusionment.

We looked at these not so much as theories that need to be understood, but as examples of formal corporate / business attempts to ‘deal with’ ambiguity in futures and understand how ideas and practices spread.

‘A good science fiction story should be able to predict not [just] the automobile but the traffic jam’: Attributed to Frederik Pohl

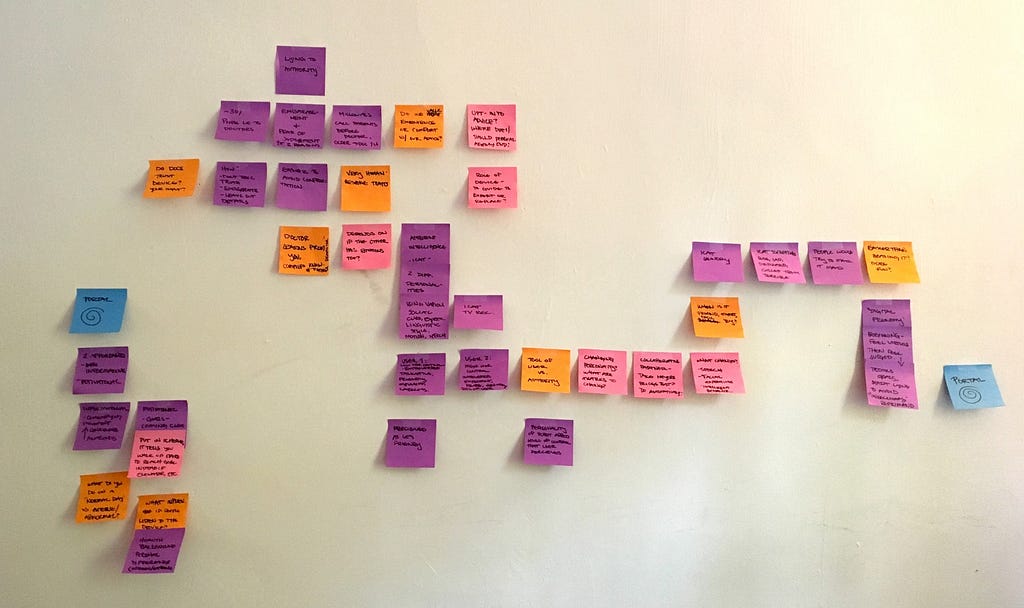

We went on to look at the idea of perhaps unanticipated consequences—side-effects and side-shows – in considerations of futures, based on part of an exercise that Veronica Ranner and I developed for a session called ‘Plans and Speculated Actions’ at the Design Research Society 2016 conference earlier this summer, with Molly Wright Steenson, Gyorgyi Galik and Tobie Kerridge.

We talked about some famous unanticipated consequences, both ‘bad’ and ‘good’, and, re-evoking Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns”, talked briefly about effects that went far beyond what could have been reasonably predicted at the outset, such as the suggested link between the introduction of tetra-ethyl lead in petrol (gasoline) and the rise (and decline) of violent crime in society in the 20th century. (It’s interesting here to note that Thomas Midgley, who developed both tetra-ethyl lead and chlorofluorocarbons, has been described as having “had more impact on the atmosphere than any other single organism in Earth’s history.”)

The distinction between side-effects and side-shows is somewhat blurred, but we might consider side-effects (in relation to cars) to include, as in the Frederik Pohl quote, immediate effects such as traffic jams and accidents , but also, potentially, longer-term effects such as obesity, changes in city planning, and, potentially—via lead—violent crime. And of course wars driven, in some part, by the quest for oil.

It’s also important to remember what might be seen as positive side-effects: widening access to travel has enabled huge changes in mobility, working possibilities (including jobs for designers!), economic development, meeting new people, cross-fertilization of cultures, and so on. And, as Robert K. Merton pointed out, even if certain effects were not specifically desired by people who planned the system, they may well be desirable for some people:

‘Undesired effects are not always undesirable effects’: Robert K. Merton, 1936, ‘The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action’, American Sociological Review 1(6), 894—904

Side-shows are the parallel-but-related developments. In relation to the car, that might mean the development of gas stations, roadside diners, car culture and everything that goes with it—which all involve design to a greater or lesser extent. They might also include frictions and counter-movements: people opting out, or being forced out, of the new norm, or finding ways to subvert it (as in Superflux’s ‘Uninvited Guests’).

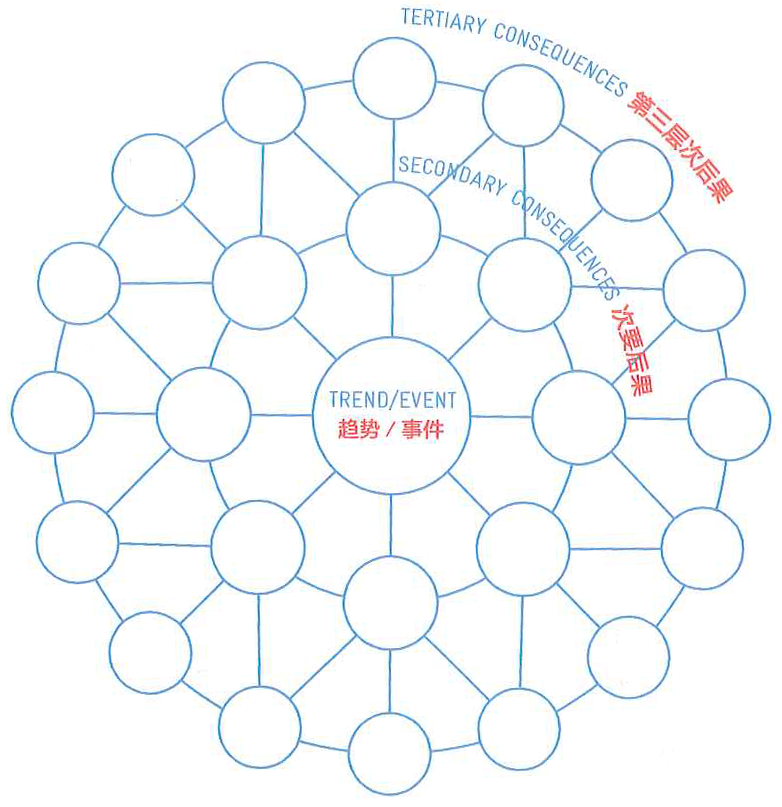

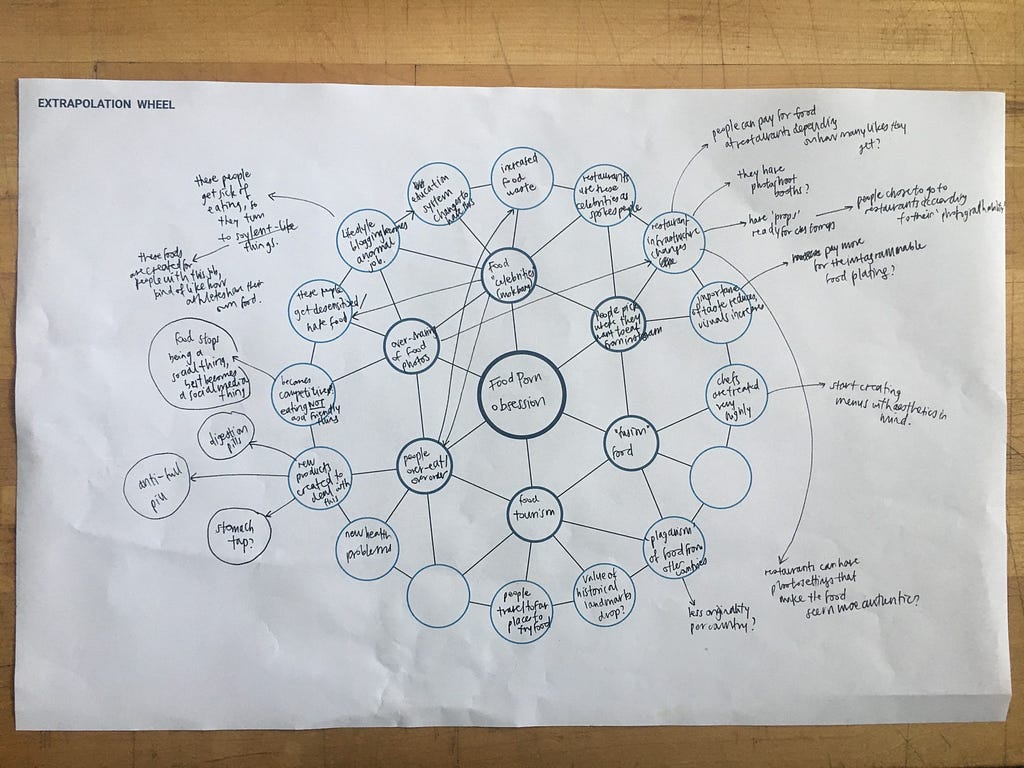

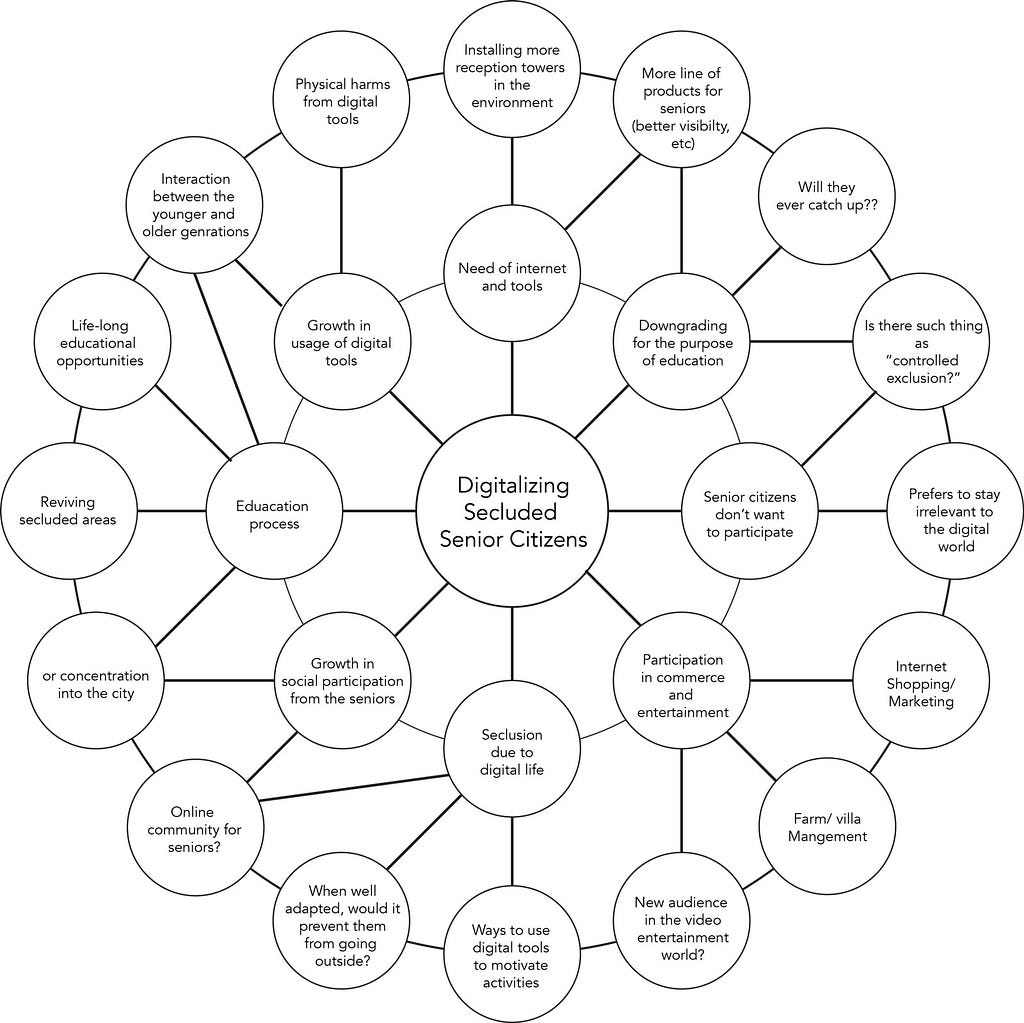

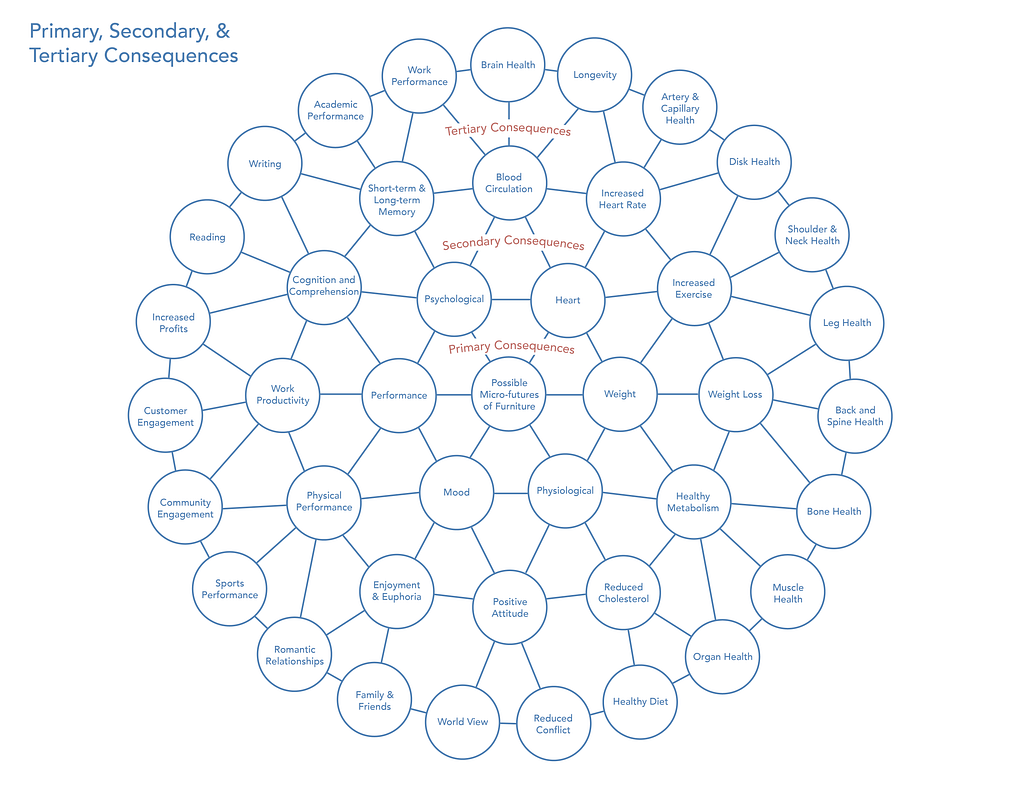

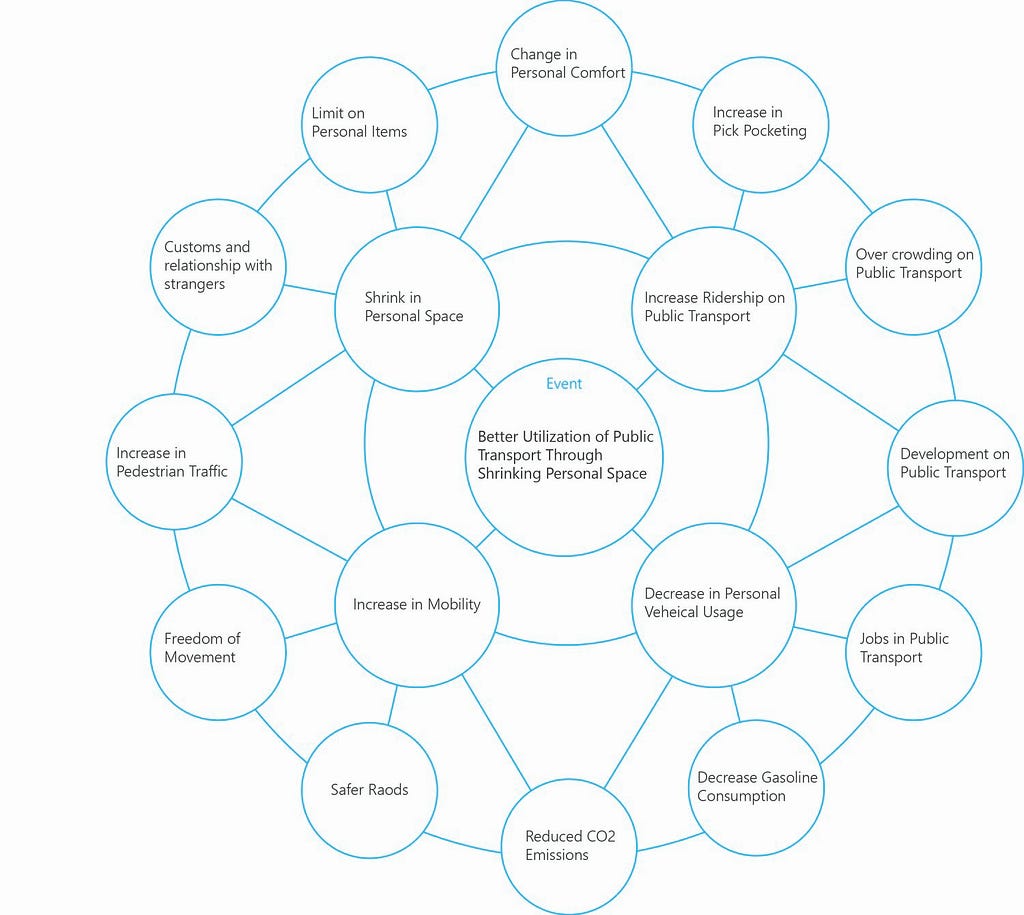

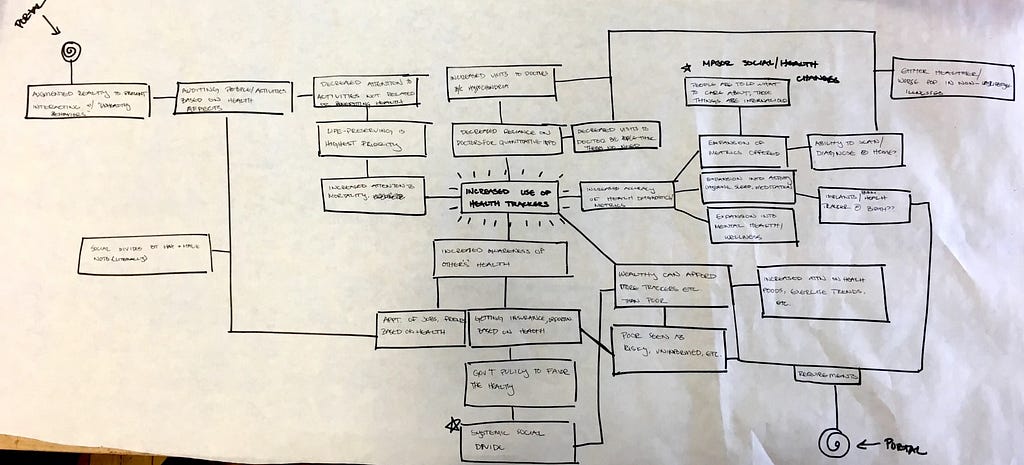

The line is blurred between side-shows and side effects, hence considering them together. There are many levels of abstraction at which systems can change, and the boundaries of how we frame our analysis are necessarily somewhat arbitrary. A version of Jerome Glenn’s Futures Wheel featured in Extrapolation Factory’s Operator’s Manual was a useful tool for thinking through side-effects and side-shows, or secondary and tertiary consequences—and some students managed to apply this very effectively to the micro-futures they had identified in Exercise 1.

Exercise 2

Pick one of the possible micro-futures you explored in Exercise 1 (or swap with someone else’s) and explore/study it further as a concept or phenomenon. (If you don’t like it, find another.)

How does it fit with the ‘ecosystem’ of people’s lives now? How could it fit in the future? How would it change daily life?

Using what you know as a designer, about both design trends and human behavior, can you extrapolate a few years into the future to create a short scenario for how things might be? (Remember, there are, of course, no ‘wrong’ predictions here, since we don’t know what we don’t know yet.)

Think through the side-effects and side-shows that might exist in this world, and the role of the designer:

- Side-effects: What consequences (potentially unanticipated—except by you!) might there be, from the new thing or way of acting? What effects could it have on society more widely? Will some people ‘opt out’ of it? Will some people rebel against it? Are there technological or environmental ‘limits’ we might reach?

- Side-shows: What other things are going on in this world? What parallel developments, related or unrelated, go along with the phenomenon you’re examining? What are the big issues in this world, the areas of public debate?

- Role of the designer: What might the briefs be for designers, in this world? What skills are in demand? How does society treat designers? How do designers treat society? Are designers mainly dealing with side-effects?

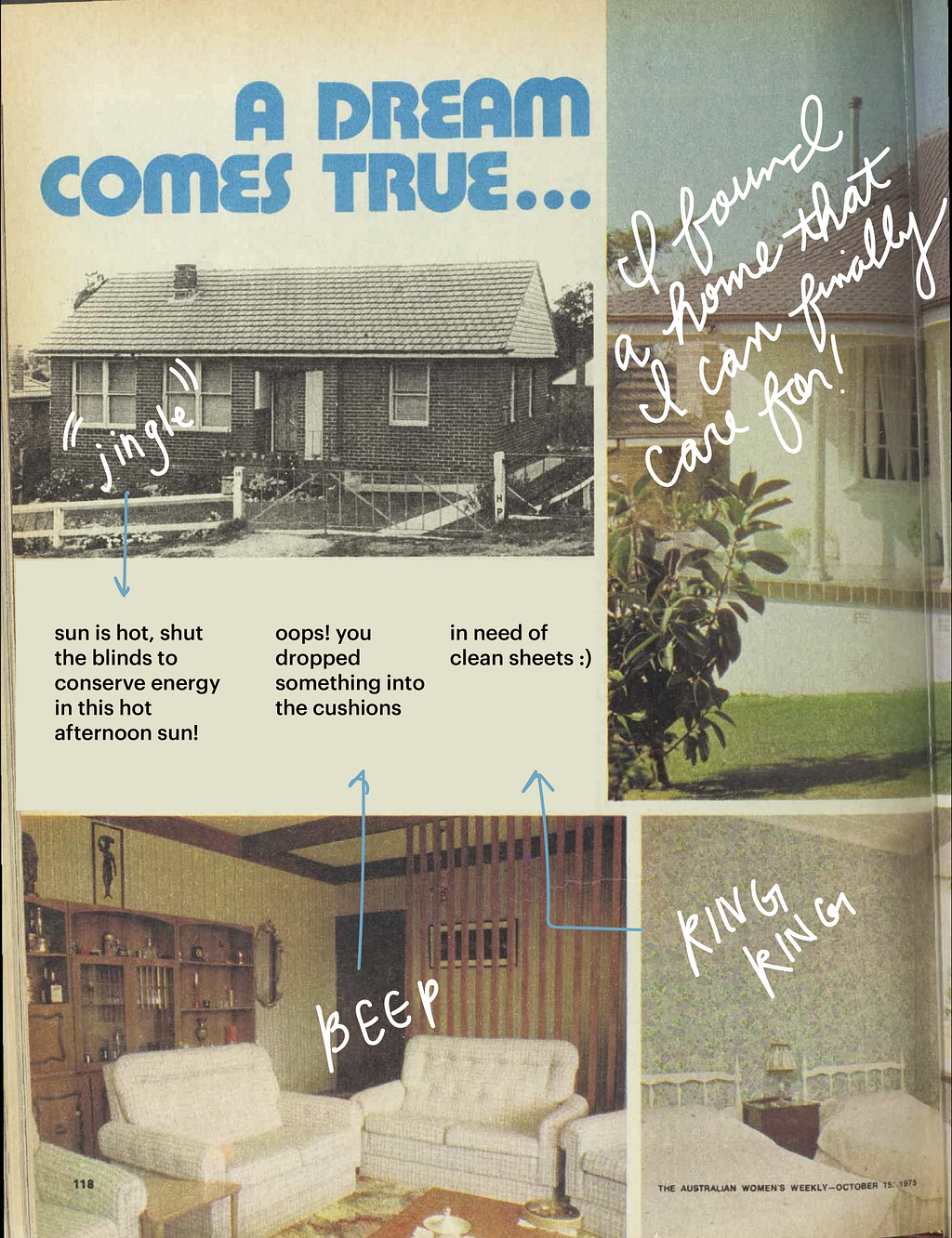

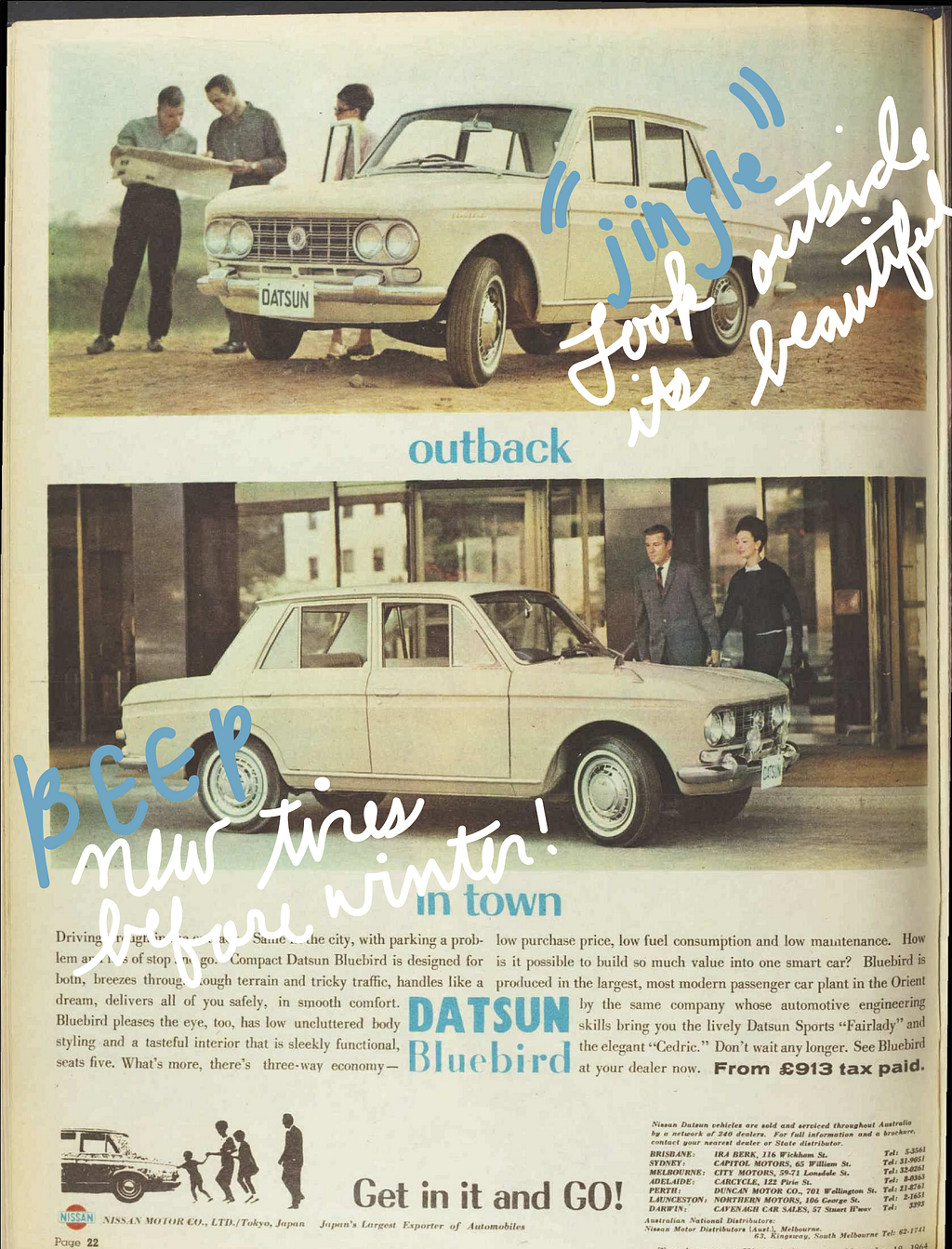

Explore these ideas visually and in text, and document them on your blog. Visually, you could sketch, take photos, collect images from elsewhere and annotate them or modify them—anything you need to do to tell your story and explain your thinking to others. In text, there’s no need for a long essay, but aim for a few hundred words. Be prepared to present what you’ve done.

Some questions to help you

These are a few (optional!) questions and things to look up which might be relevant, depending on how ‘big’ the idea is that you’re working on.

Questions about ethics

—Look up Kant’s ‘categorical imperative’. What would happen if this new behavior, object, etc, became universal, i.e. if everyone acted or were influenced in this way? Would you envisage that that this ‘should become a universal law’? If not, why not?

– Look up Rawls’s ‘Veil of Ignorance’. What are you, as a designer, assuming your status would be in the world you envision? Would you support the idea if you didn’t know what place you would have in the scenario, what background you would have, and whether you were on the ‘receiving end’?

Questions about sustainability

If you are thinking about ‘sustainability’, what definition are you using, tacitly or explicitly? Where is the boundary drawn between humans and nature? Is your treatment of sustainability primarily ecological, or does it include a social component?

Questions about power

Would this world involve one group of people having power or advantage over others? Would it create new power structures in society, or reinforce existing power structures? Or could it break down existing structures, and give different people agency to change the system?

These questions are based on some in a forthcoming book chapter by myself and Veronica Ranner: Lockton, D. & Ranner, V. (2017). ‘Plans and speculated actions: Design, behaviour and complexity in sustainable futures’. In: J. Chapman (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Product Design, Routledge, London.

Readings for Exercise 2

- Julian Bleecker, 2009, ‘Design Fiction: A short essay on design, science, fact and fiction’. http://blog.nearfuturelaboratory.com/2009/03/17/design-fiction-a-short-essay-on-design-science-fact-and-fiction/

- Stuart Candy and Jeff Watson, 2014, ‘The Thing from the Future’. http://situationlab.org/projects/the-thing-from-the-future/

- Donella Meadows, 1997/1999, ‘Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System’. http://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/

Students’ blogs for Exercise 2 (non-public ones not listed)

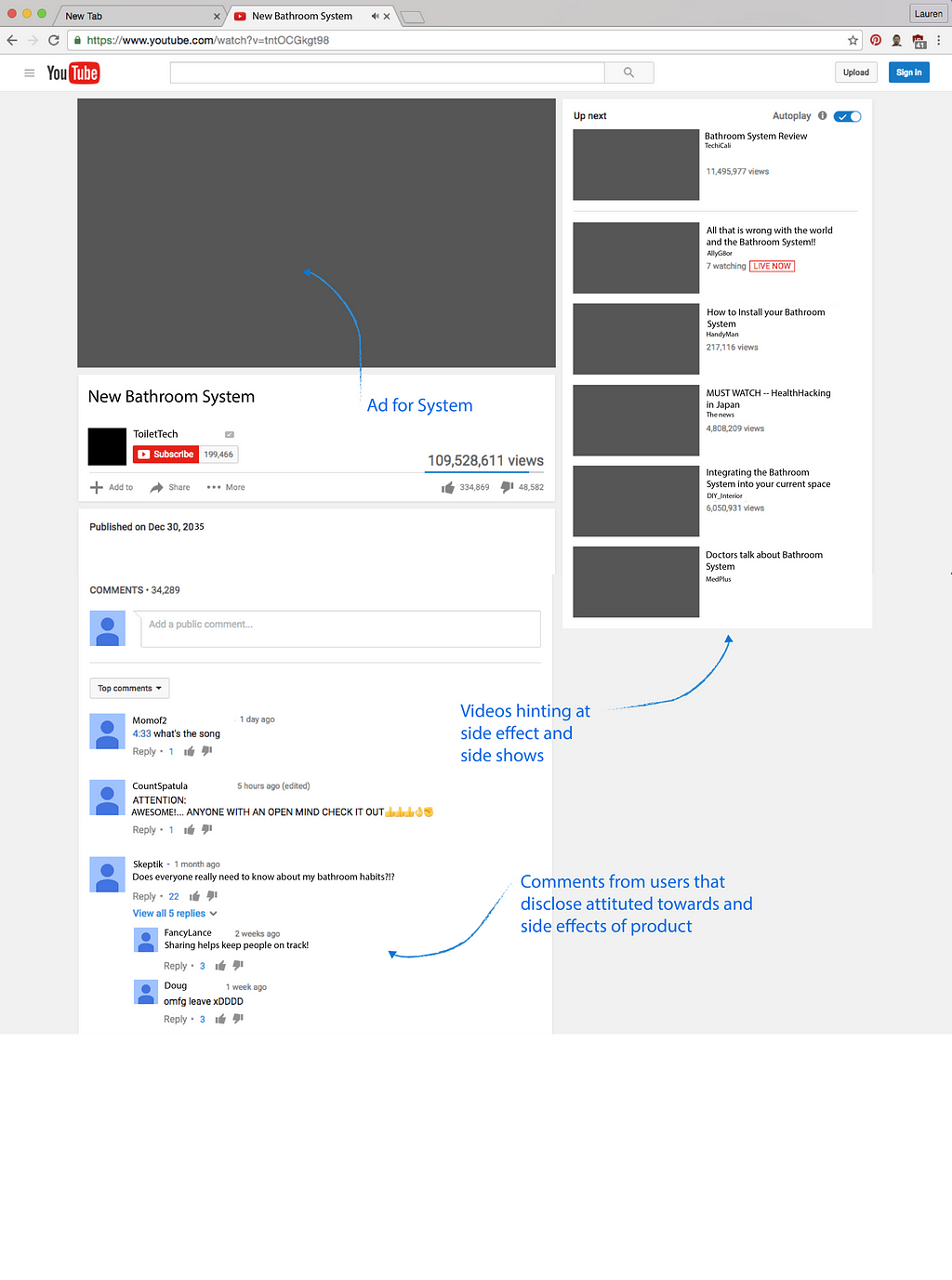

Lauren Zemering: Discussing bathroom habits

Jiyoung Ahn: (1, 2) Minimalism and language

Brandon Kirkley: FashionTech—Politics, stigma, and a new layer of interpersonal interaction

Albert Topdjian: Artificially Creating the Natural

Kaitlin Wilkinson: Creating physical artifacts from our social media

Jonathan Don Kim: Concurrence of technology and various industries

Rachel Headrick: Ascribing a Different Meaning to Apple iPhone Sound-effects

Rachel Chang: Death does not mean the end

Diana Sun: Internet of Things & Smart Homes

Courtney Pozzi: What if the things we owned were alive?

Praewa Suntiasvaraporn: (1, 2) Food obsession

Jillian Nelson: (1, 2) Sousveillance and reflectionism

Leah Anton: Multitasking

Vicky Hwang: Seniors and digitalizing world

Jackie Kang: How Google as a whole might affect our society in the future

Zac Mau: Technology truly seamlessly blending into our lives

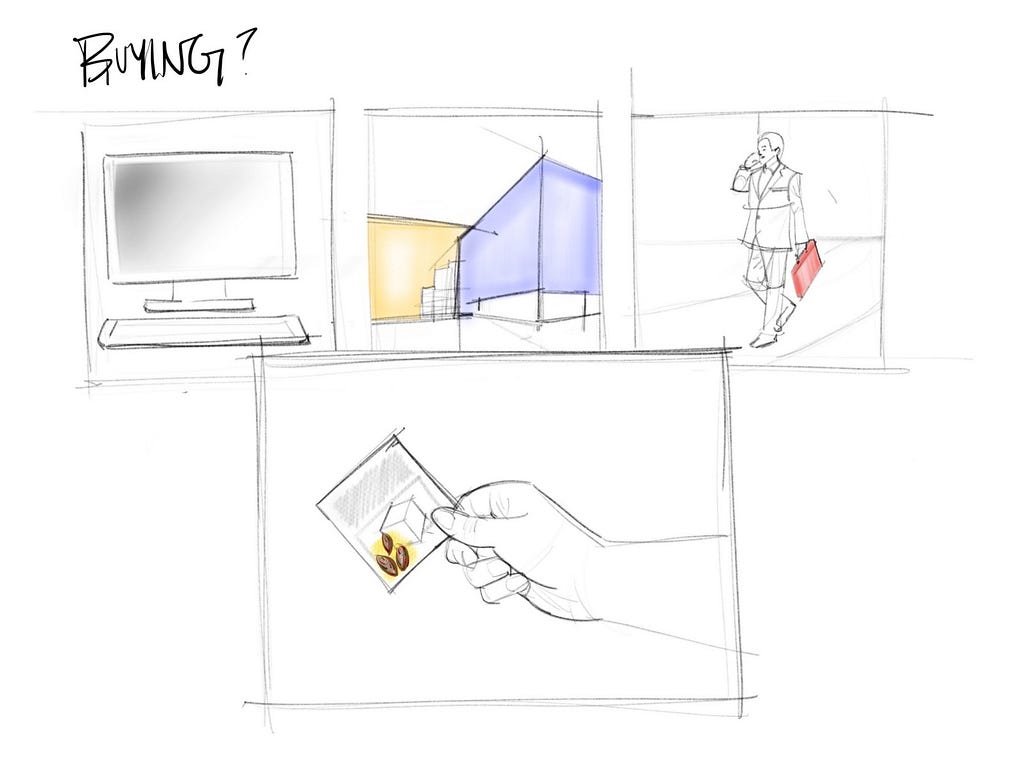

Brian Yang: Better Utilization of Public Transport Through Shrinking Personal Space

Catherine Zheng: Prescriptive lifestyles

Lea Cody: Health tracking

Gabriel Mitchell: The Ephemeral Interface

Zai Aliyu: How might emotional intelligence in technology help us better express ourselves to others, empathize with others, or improve day-to-day interactions? In this faster moving world, how might the integration of ephemerality into our day-to-day lives change the way we interact, share, and connect with others, as well as our perception of identity?

Kate Apostolou: What is the future of spatial thinking in a world where people depend entirely on technology (smartphones and self-driving cars) to get around?

Kaleb Crawford: What does a future look like where online content and copywriting is algorithm driven, not personally authored?

Ruby He: A New Age of Communication: Conversations with Machines

Alisa Le: Future of gender

Julia Wong: Flexibility and mobility

Jeff Houng: A Biometric Future

Exercise 3: Storytelling scenarios

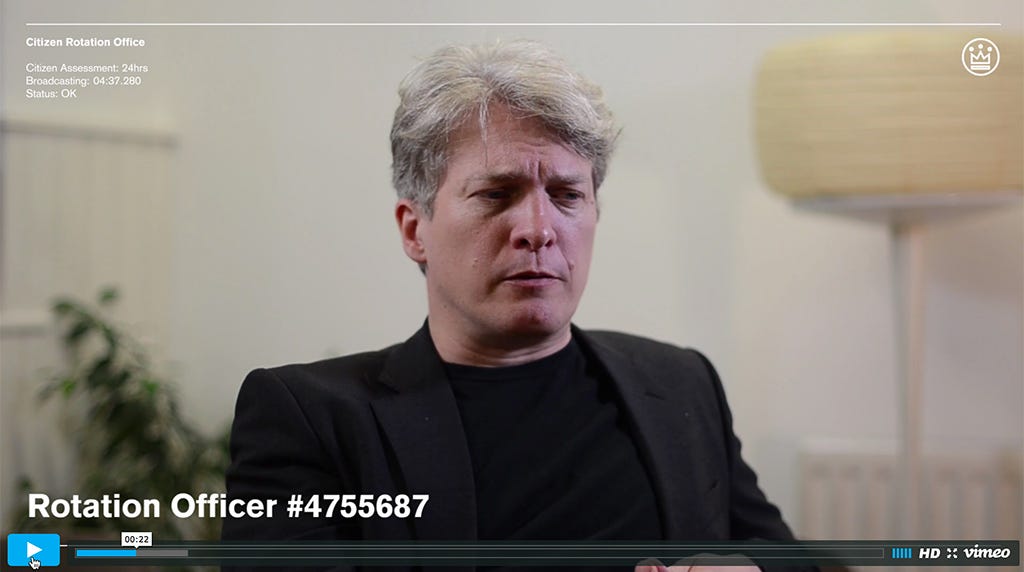

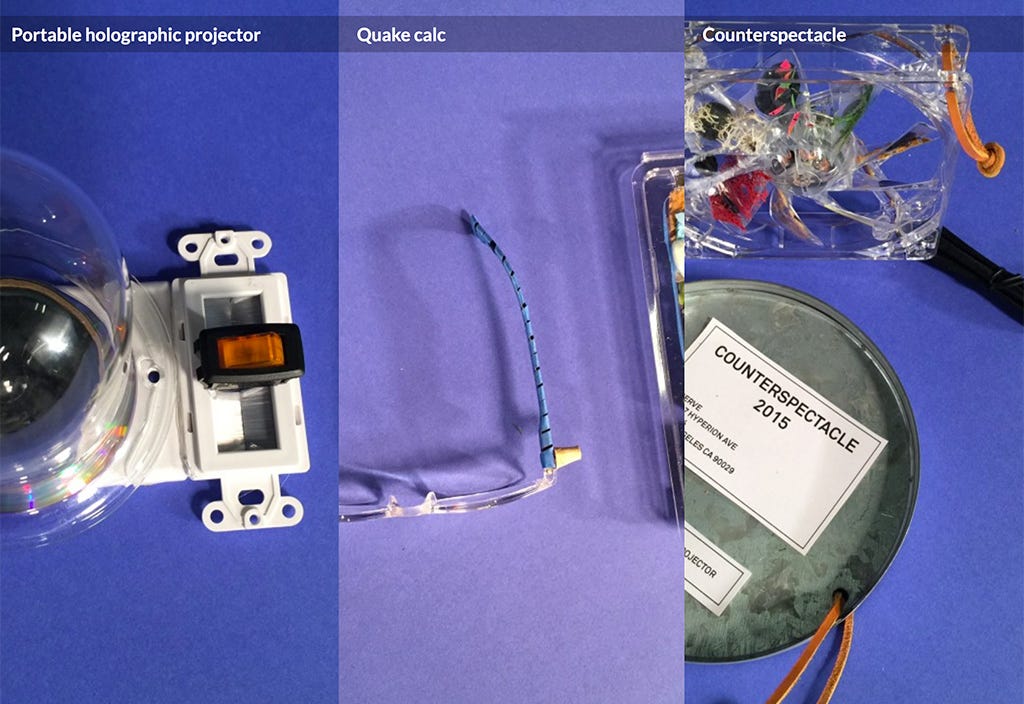

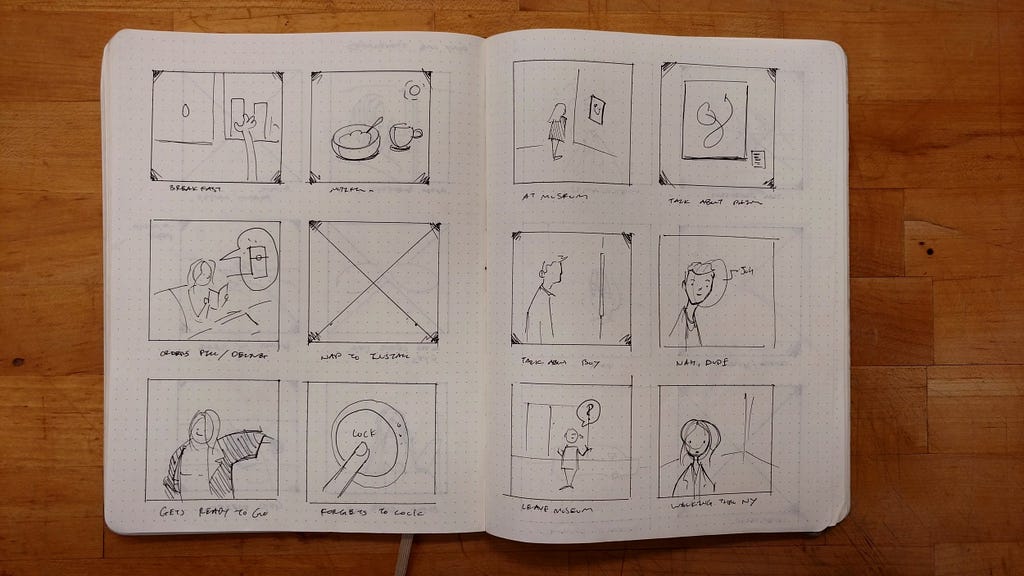

Throughout the class, we looked at a variety of examples of design fiction, speculative design and other forms of making futures (and alternative pasts and presents) experiential—or at least tangible—through design. We explored the notion of diegetic prototypes and design fictions as detailed by David Kirby, Bruce Sterling and Julian Bleecker, and the influence of Hollywood, and popular visions of ‘the future’, including the very current Black Mirror, on how we as designers imagine what might exist, and what might be designed to bring that ‘alive’ to an audience. A major part of bringing the futures alive was finding ways to incorporate some of the side effects and side-shows uncovered in Exercise 2, either directly as part of a story, or through developing a scenario in which some designed product or service responded to those side-effects.

The aim of looking at existing examples was partly to consider the speculated futures themselves, but also to evaluate and critique the designed forms in which those ideas were presented, and relate them to the skills and ambitions the students have, and what might be achievable to create within a short period. So, from newspapers to photoshoots, websites to day-in-the-life videos, comics to service blueprints, renderings to prank product packaging, we examined these forms as potential models and inspirations, for their effectiveness and limitations.

It is important to remember: these were going to be undergraduate student projects, to end up in portfolios, be seen by potential employers and be shown in the end-of-semester exhibition—they needed to be comprehensible to an audience without extensive introduction or background-setting, and, while they could be amusing or serious, they needed to demonstrate the skills the students wanted to exhibit. Telling a story somehow, through either acting a scenario or showing us artefacts from that scenario (or both), seemed to be a good way of doing this, and we looked at some basic story forms via TV Tropes, Kurt Vonnegut and Plotto.

We benefited from a very useful guest lecture by CMU’s Bruce Hanington, co-author of Universal Methods of Design, on methods of quick prototyping and ways to get low-fidelity feedback, including bodystorming, experience prototyping, Wizard of Oz and Will Odom’s ‘User Enactments’ method.

Todd Zaki Warfel’s “If you can’t make it, fake it” seemed to be a running theme here, and indeed, as used very effectively in Near Future Laboratory’s Curious Rituals: A Digital Tomorrow, the use of ‘off-screen’, invisible or audio interfaces or systems which are perhaps ‘seen’ by the people in the story but whose presence is only implied to the viewer.

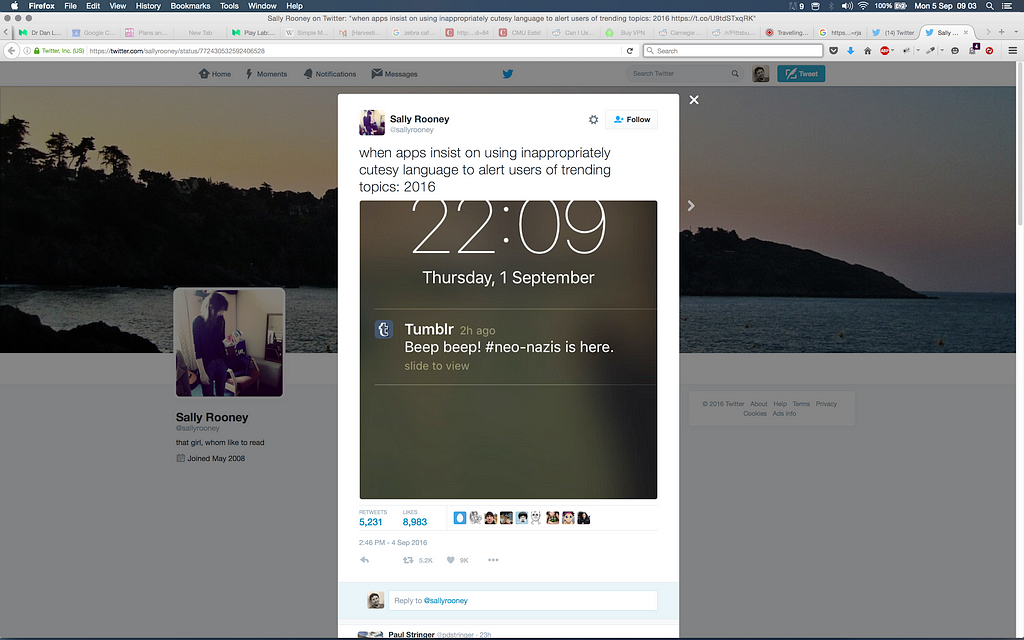

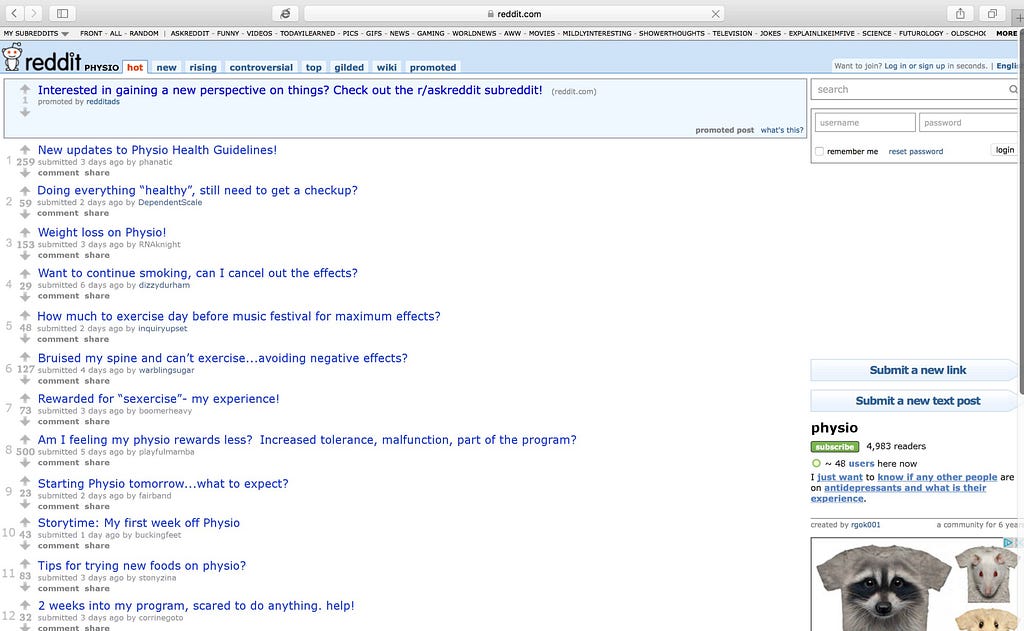

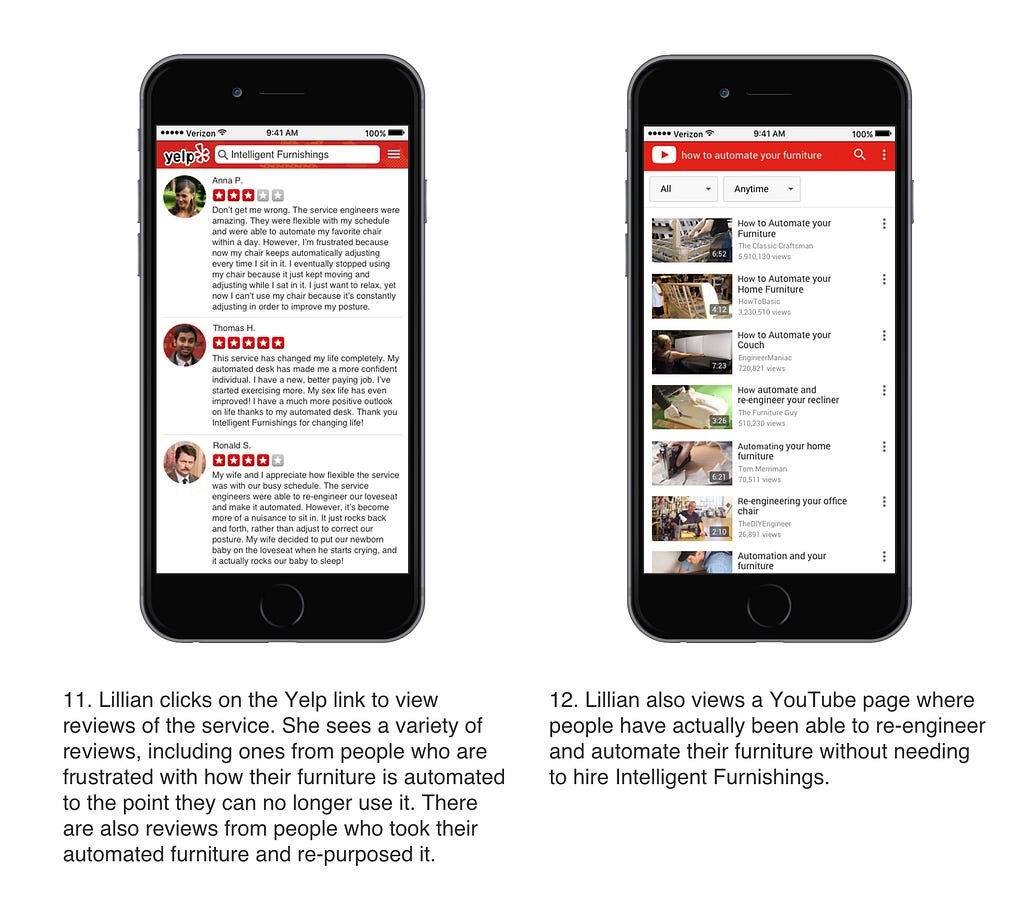

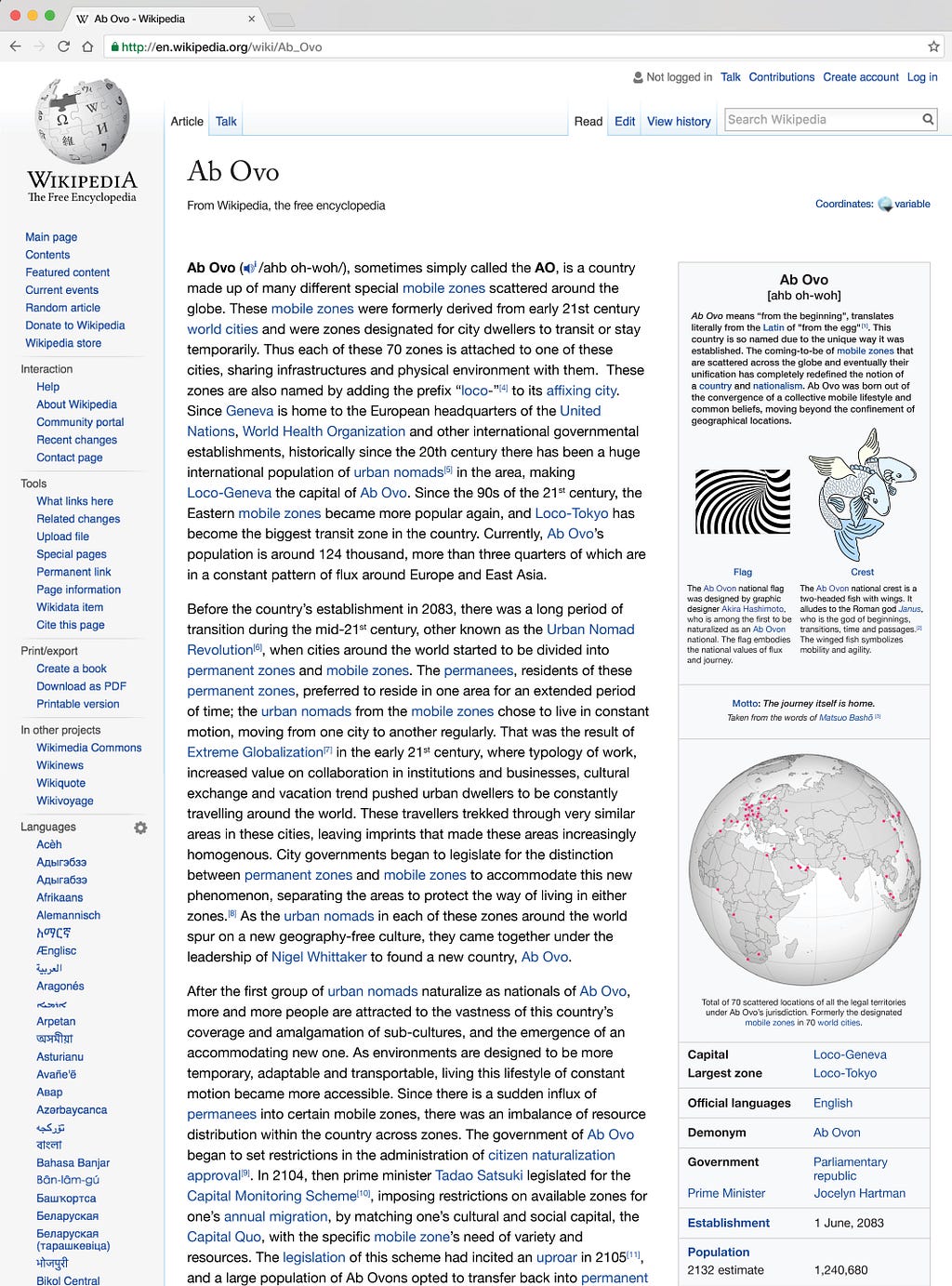

Digital meta-artefacts

One novel, contemporary form which emerged was the creation of digital ‘meta-artefacts’: not just webpages, but search engine results pages, reviews, forums, subreddits and even Wikpedia articles as design fictions, particularly to show the side-effects or side-shows, or other consequences of the main idea. Starting with Lauren Zemering, who saw the value of technology blogs and reviews as a potential way to highlight side-effects, students explored a range of media and platforms. I have no doubt that some of these have been done before in design fiction contexts, but the Play Lab students certainly took them in some interesting directions:

But this is getting ahead of ourselves somewhat. Exercise 3 was intended to help students start to world-build, to create a scenario in which the trend they identified in Exercise 1, and the side-effects and side-shows explored in Exercise 2, started to come together, as a way of providing a structure for Exercise 4 where the ‘future’ would be made. In some cases students pivoted from, or evolved significantly, the ideas they had initially been exploring, to produce a story which better fitted what they were interested in.

Exercise 3

Create a scenario around the future(s) world(s) that you’re gradually exploring. What is a ‘realistic’ (maybe) everyday (maybe) situation that might exist in this world? What are the behaviors? What are the ambiguities? What is expected vs uncertain? Try to preserve some ambiguity: do you understand everything about the world around you now? Would you expect to do so in the future?

Build a story around your scenario—bearing in mind that in Exercise 4, you will be ‘making’ parts of it, so if particular objects or settings are going to be important in the story, think about how you might do this. If you need to do so, work in pairs or groups of 3 to plan how to act each person’s story out (you’ll need one story one per person in the end—so split your time accordingly). Don’t script everything in detail, but work out some possible roles for different people and the general outline of a story.

The ‘deliverable’ is:

– notes on the scenario / story and people’s behaviors (on your blog)

– notes on what objects or situations you might need to ‘make’ later (on your blog)

– a brief run-through in class of the outline of your story (not a full-on dramatic production)

Readings for Exercise 3

Nicolas Nova, Katherine Miyake, Walton Chiu & Nancy Kwon, 2012. Curious Rituals: Gestural Interaction in the Everyday.

David Kirby, 2010. ‘The Future is Now: Diegetic Prototypes and the Role of Popular Films in Generating Real-world Technological Development’. Social Studies of Science 40(1), p. 41—70

Students’ blogs for Exercise 3 (non-public ones not listed)

Lauren Zemering: (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) Scenario development for Hygienie

Jiyoung Ahn: (1, 2) Scenario development for a new language

Brandon Kirkley: (1, 2, 3) Scenario development for FashionTech

Albert Topdjian: Scenario development for a future where green spaces become personal

Kaitlin Wilkinson: Scenario development for a future museum exhibit of personal documentation

Rachel Headrick: I Live in Channel 32

Rachel Chang: Scenario development for bots built from the digital trail individuals leave behind

Diana Sun: Scenario development for Home Smart Home

Courtney Pozzi: Scenario development for GeneX, the future of genetic engineering through a for-profit firm

Praewa Suntiasvaraporn: (1, 2) Scenario development for future of food and celebrity

Leah Anton: Scenario development around multitasking

Vicky Hwang: (1, 2, 3) Scenario development for The Senior Millennial

Jackie Kang: (1, 2, 3, 4) Scenario development for Google’s presence in the future

Zac Mau: (1, 2) Scenario development for thought-based interface

Brian Yang: Scenario development for Tiny Home X Big City

Catherine Zheng: Scenario development for Prescriptive lifestyles

Lea Cody: Scenario development for Health Improvement System

Gabriel Mitchell: Scenario development for ‘When everything can talk’

Zai Aliyu: Scenario development for An Ephemeral Future and Intentional Impression Management

Kate Apostolou: Scenario development around the dérive

Ruby He: Scenario development around Conversations with Machines

Alisa Le: Scenario development around Raising the Gender-Neutral Generation

Julia Wong: (1, 2) Scenario development around traveling in the future

Jeff Houng: Scenario development around Hyper-personalization leading to experiential echo-chambers

Exercise 4 and 5: Make an experiential ‘pocket’ of a future; reflect, critique and document

The final segment of the class, approximately the last 2½ weeks, was spent as studio sessions where students developed and implemented their scenarios from Exercise 3 in an experiential, or at least presentable, form, with regular desk crits and discussion with each other. The third group of students did this alongside preparing Focus, their senior design exhibition, but some students from this group nevertheless managed to get their Play Lab projects done in time to have on show.

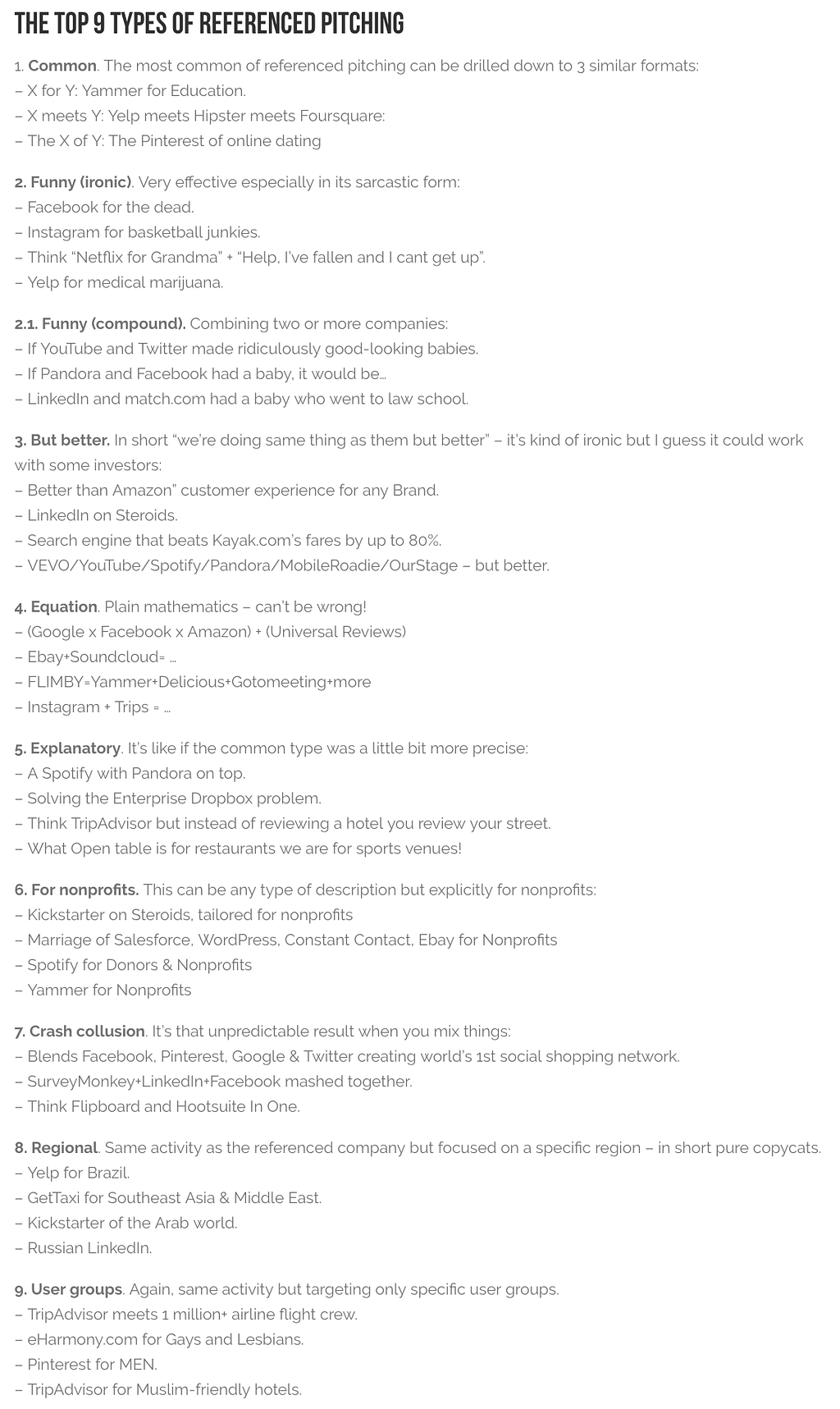

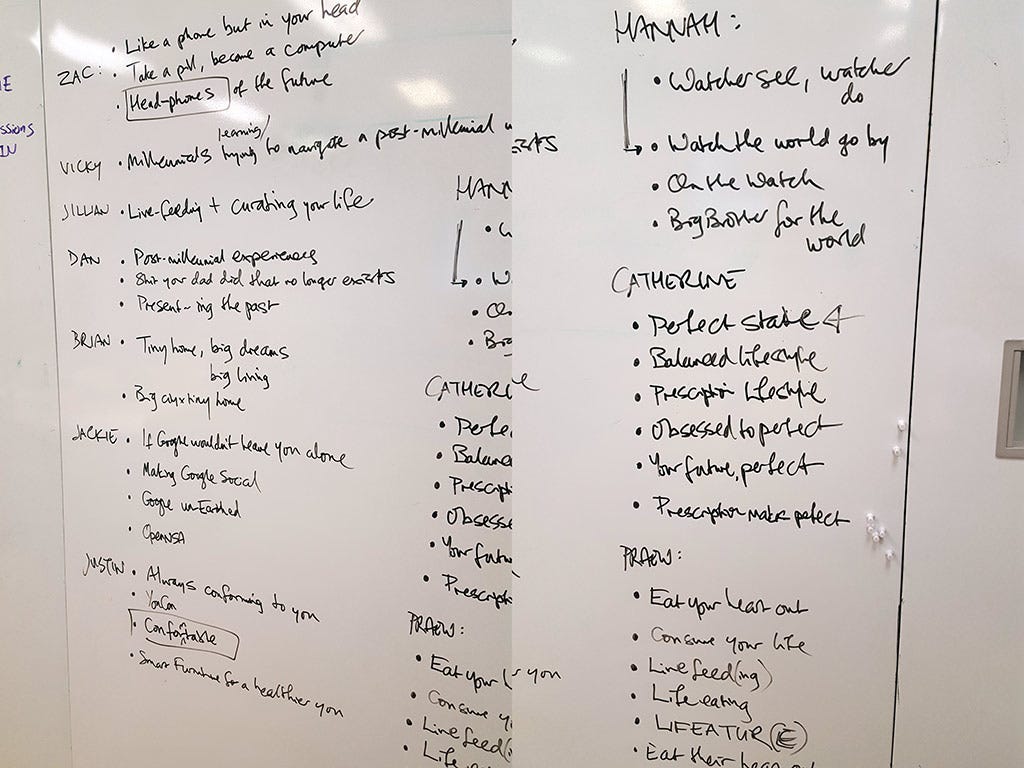

As well as continuing to look at examples of design fictions of different forms, we also did a group exercise to generate taglines and project titles for each other’s projects (based around the notion that if someone else can explain your project back to you, they probably understand it). After looking at some famous movie taglines and the ways in which they perhaps hint at the story but did not give it away, we also examined the phenomenon of the one-line elevator pitch, which often references other, existing products or services.

It’s clear that while these will often relate to very specific, current contexts, there are some structures which could almost be used generatively for creating (and explaining) speculative concepts, e.g. “Facebook for the dead” or “LinkedIn on steroids” in Chris Eleftheriadis’s list. In the event, the Play Lab students variously found these approaches useful or not, with a few usable taglines and project names being generated: Courtney Pozzi’s “First we cured cancer, now let’s cure ugly”, Hannah Salinas’s “Watch the world go by” and and Lea Cody’s notion of a “hangover for your whole life” being particularly memorable.

Here’s the brief the students had:

Exercise 4 and 5:

Make an experiential ‘pocket’ of a future

Create a way for an audience to ‘experience’ the future you are exploring, through bringing your story /scenario to life somehow in a form which can be presented. This could involve objects / artifacts, a website, illustrations, a video or a performance which you or others ‘act’ out, or maybe something that the audience can interact with. The aim is that an audience is able to get slightly more than a glimpse of this future, but also some of the frictions, ambiguities, tensions and uncertainties in it—what are the side-effects, the side-shows, the issues?

The deliverable for this is a 5 minute maximum presentation (+3 mins of questions) of your ‘pocket of a future’ (this might be the wrong term!).

Reflect, critique and document

On your blog, write a short (500—800 word) reflection on the role of designers in this possible future. Has it come about through design, or through external factors? Are designers in this world acting within the story or scenario, or acting to oppose it? What could a common brief be for a designer (or design student) in this world?

Also, reflect on your speculation itself: is this a future you want to be part of creating? If so, how do you get there? If not, what do designers need to do now to prevent it? Make sure that your blog overall documents your process throughout Play Lab, including the development of ideas through Exercises 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Readings for Exercise 4 and 5

Georgina Voss, Tobias Revell and Justin Pickard, 2015. Speculative design and the future of an ageing population: outcomes and techniques reports: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/future-of-ageing-speculative-design-workshops

Anne Galloway, 2014. Counting Sheep: NZ Merino in an Internet of Things. http://www.countingsheep.info/

WIRED magazine, various dates. ‘Found: Artifacts from the future’ gallery, collated by Stuart Candy at https://futuryst.blogspot.ca/search/label/ Found%20gallery

Discussion of the final projects

All the projects are featured at cmuplaylab.com, but it’s worth some discussion here of the trends that were apparent, and the variety of ways in which students tackled the issues they worked on. Over the course of the three groups, some larger themes emerged, which I attempt to summarize here. The preoccupations of imagined futures inevitably represent reflections on many of the issues of concern in the present, and perhaps tell us more about ourselves right now than we might first appreciate.

Our environment

‘Smart’ homes

Many students were interested in ideas of the evolution of artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, the usage of our data, and ‘intelligent’ devices more generally (see below). But two projects in particular explored the everyday environment of the ‘smart’ home and what it might be like to live in a context where our devices talk to us, day and night.

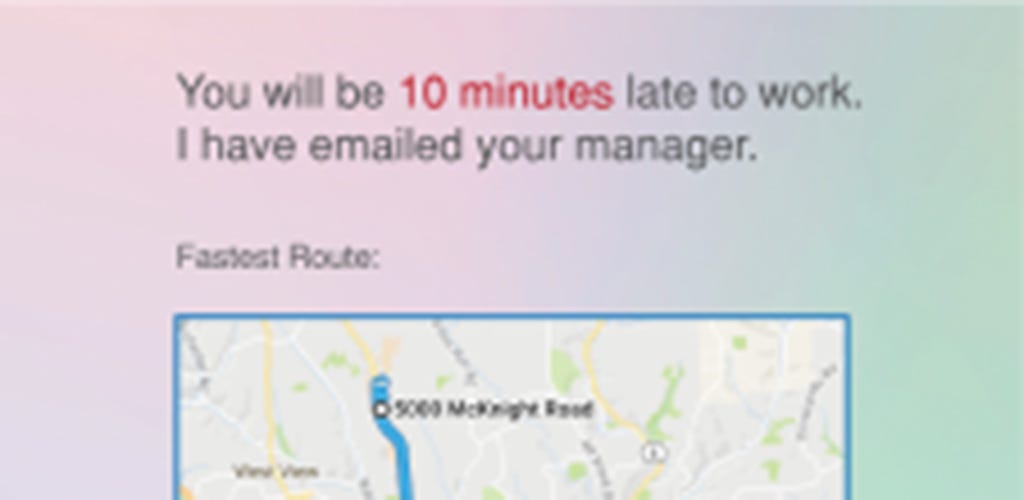

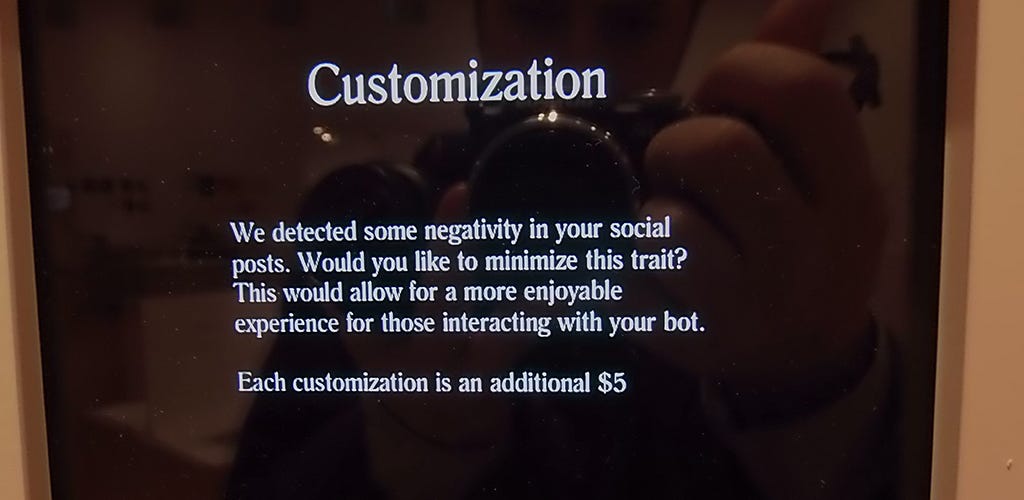

Gabriel Mitchell’s Nes.0 Bot focuses specifically on one device, while Diana Sun’s Home Smart Home looks at the convergence of multiple systems. Are our homes still ‘ours’ when they contain appliances with so much agency of their own? Diana reflects on her project here while Gabe’s reflection accompanies the video here.

The future of place

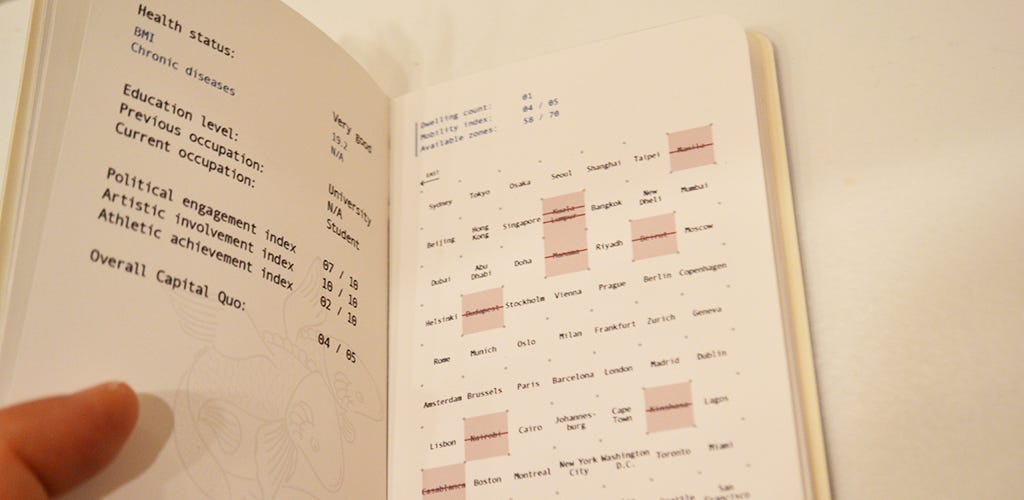

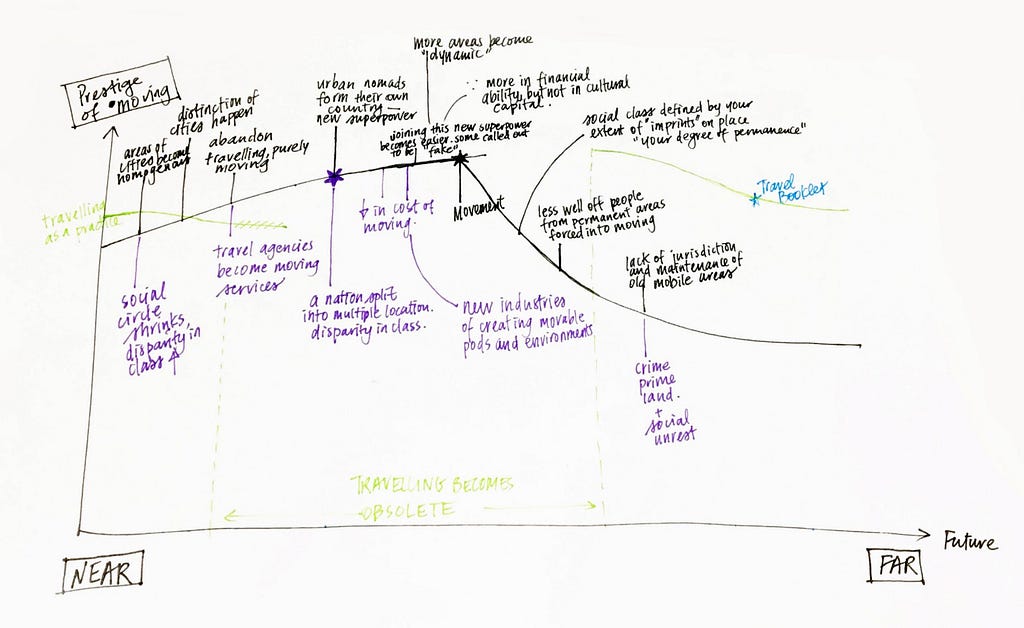

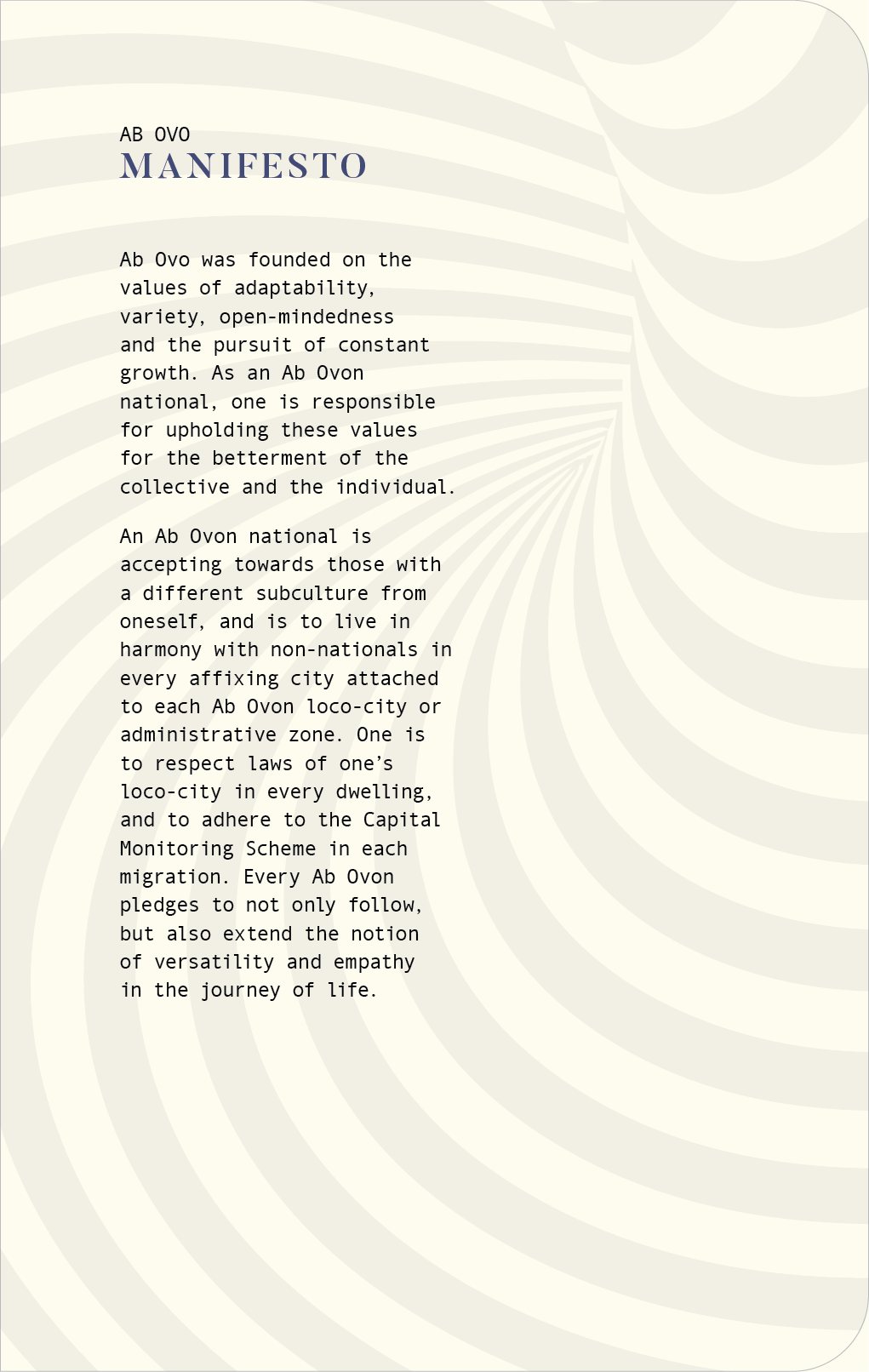

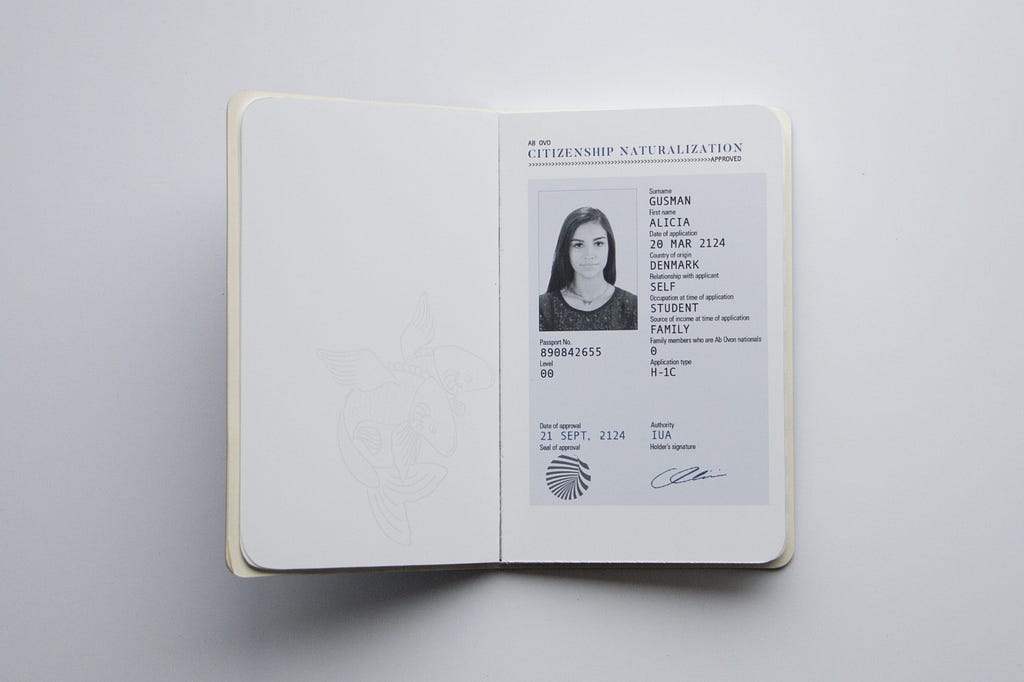

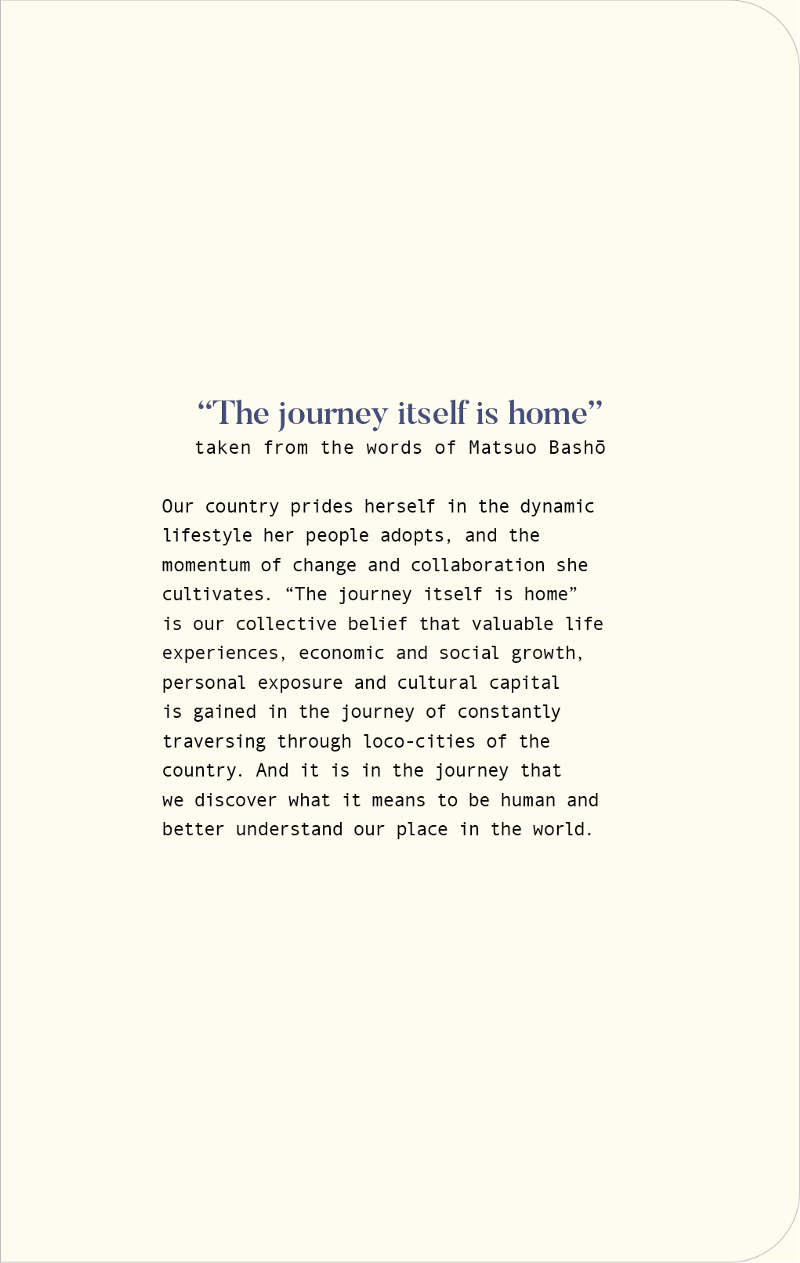

Outside the home, four projects looked at what we might think of as futures of place, at different scales. Via a passport, travel guide and a Wikipedia page, Julia Wong’s Ab Ovo (1, 2, 3, 4) examines this globally, “extreme globalization leading up to the designation of permanent and mobile zones in cities and eventually the formation of a new culture and nation… due to the transition of economic needs and ultimately a progression of human values on a global scale.”

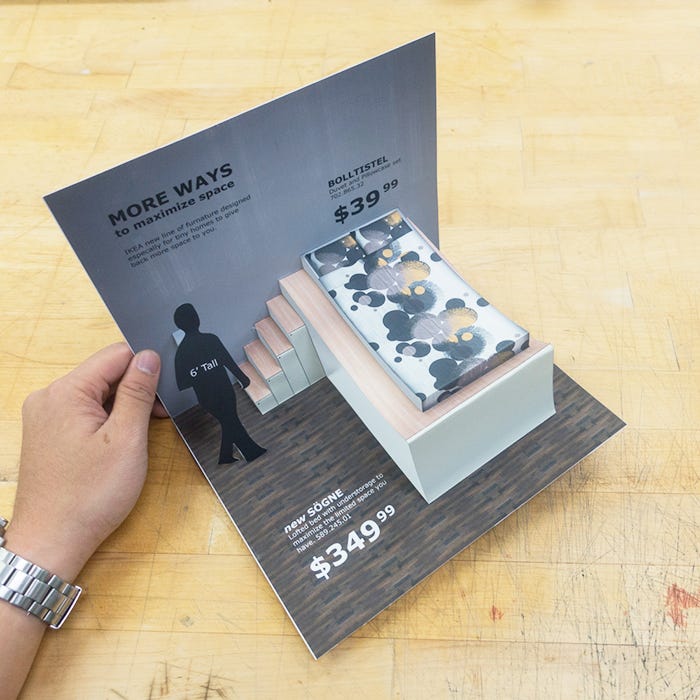

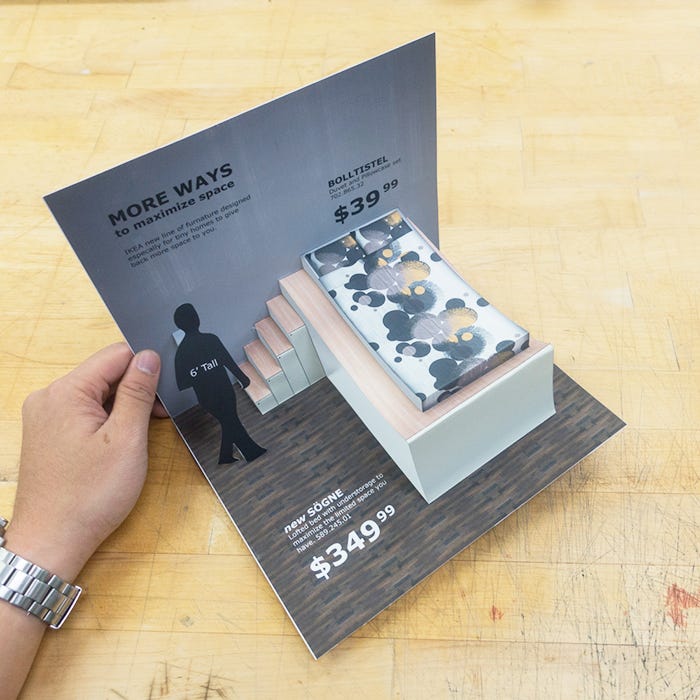

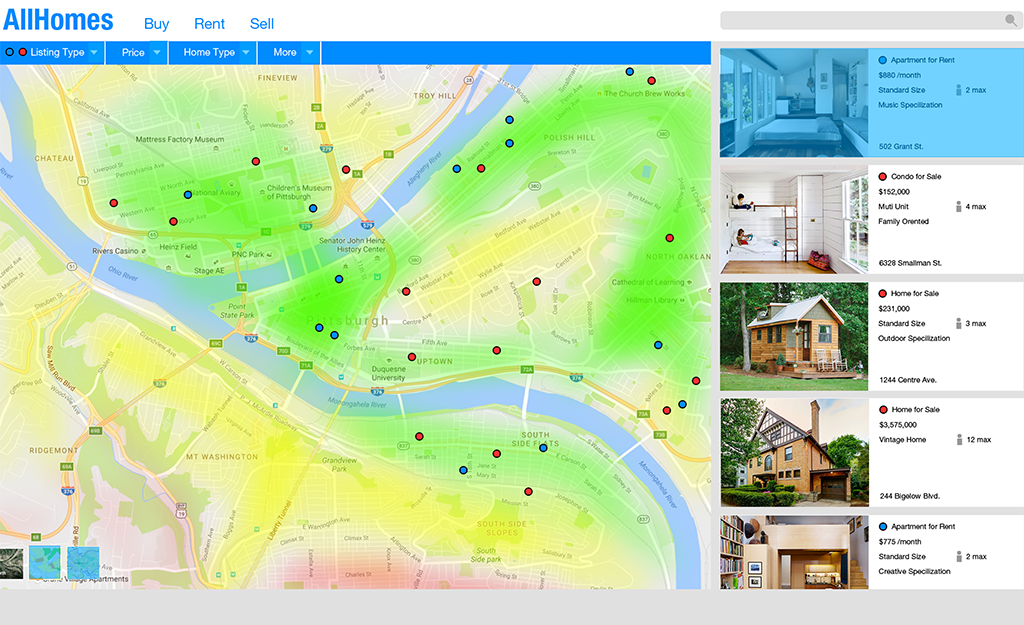

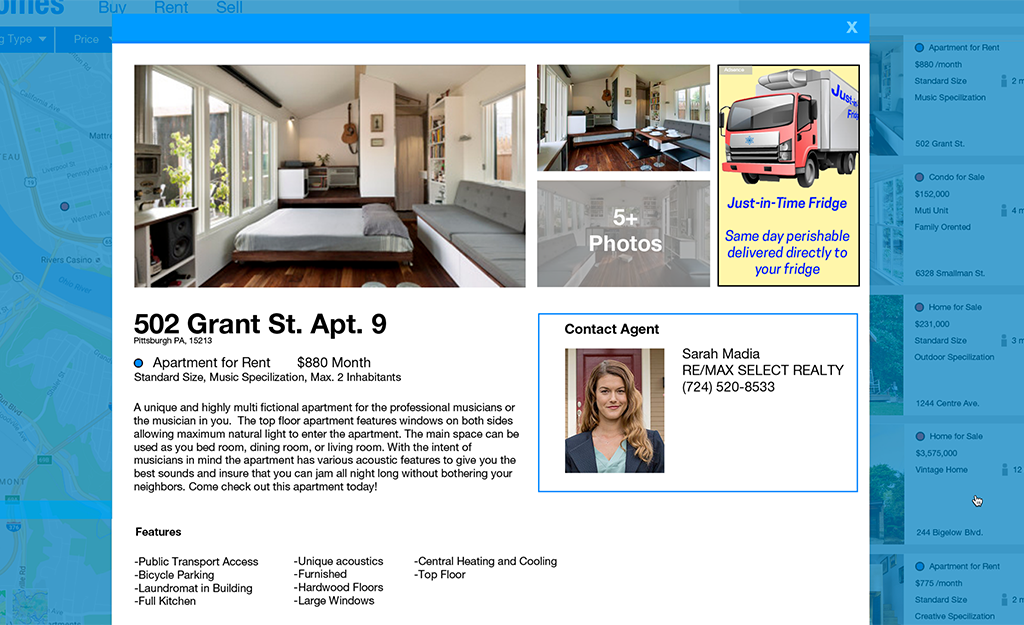

Brian Yang’s Big City X Tiny Home imagines a future where tiny homes become increasingly the default for city living as population rises. Through a property website and a clever fold-out IKEA advertising flyer, Brian explores how renters might find the homes, and what might be important to them (how to choose furniture, which amenities are shared, and so on).

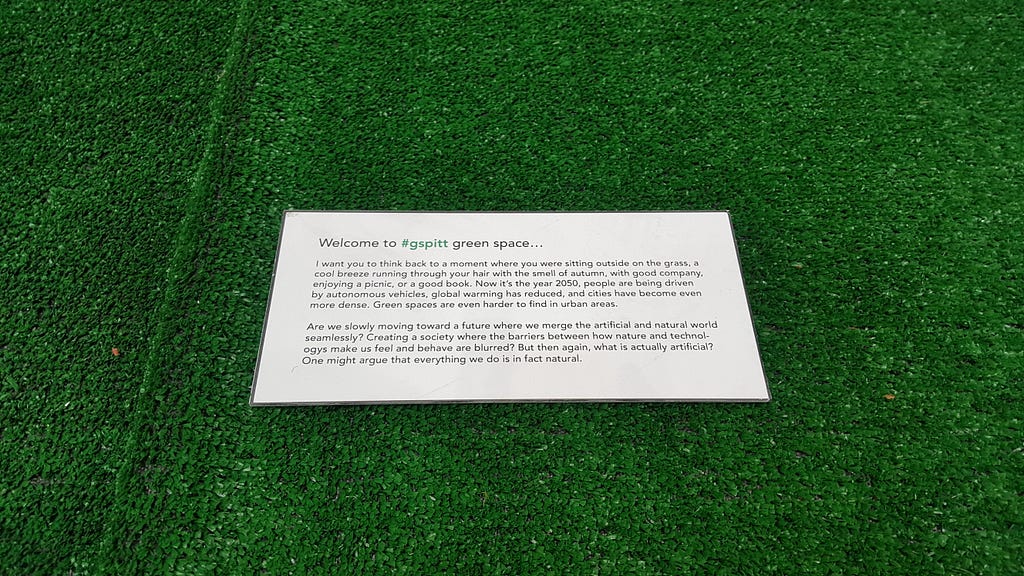

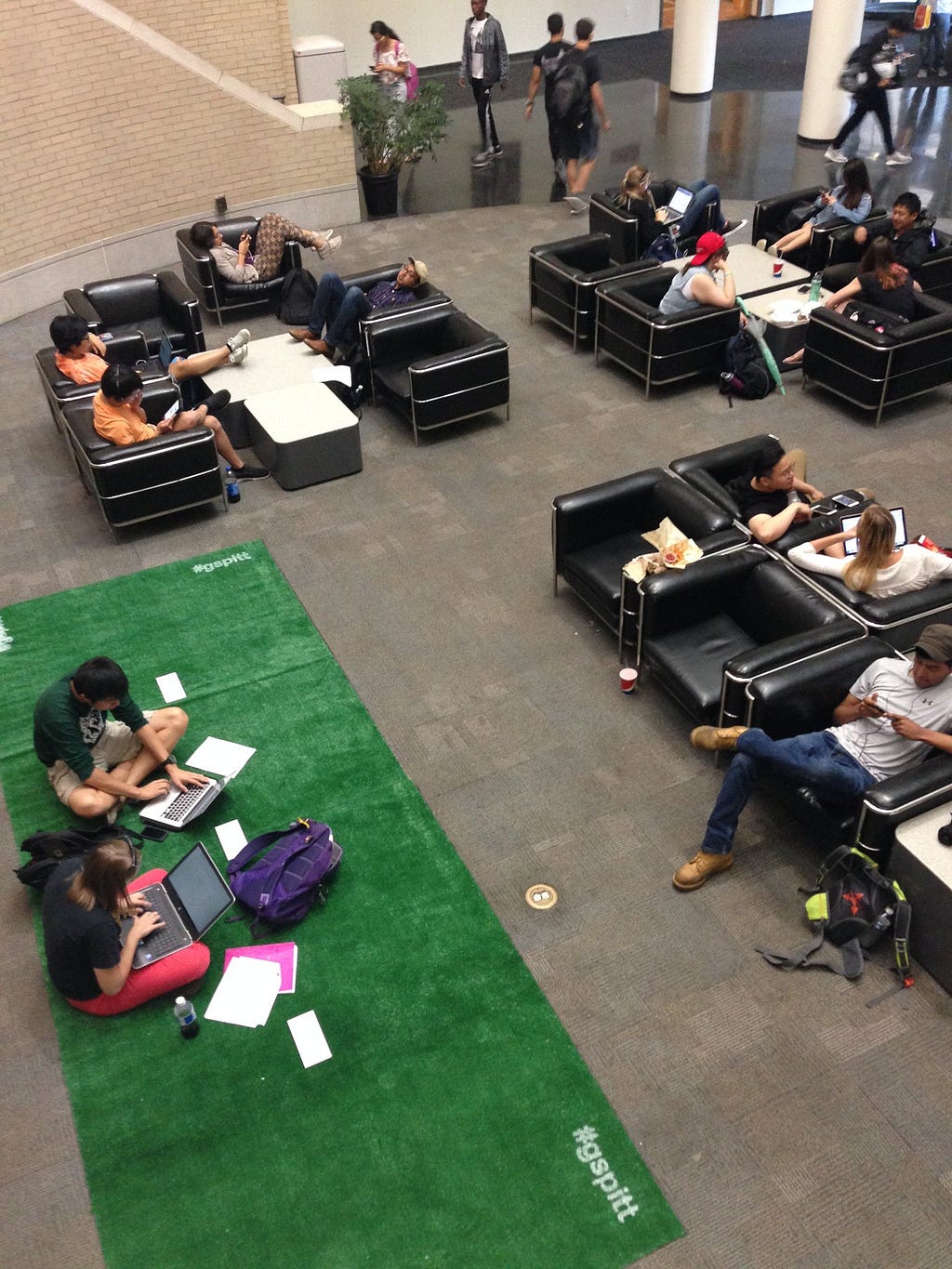

Albert Topdjian’s Green Space Initiative (e.g. 1, 2, 3) is an intriguing experiment in actually making the imagined future experiential in the present. The project envisioned a situation “where the density of city populations increases, and the available green spaces diminish, citizens can retreat into their personal/public indoor green rooms. There, one can relax, reflect, and socialize like it was in the good ol’ days of public parks, and green lawns.” Albert brought this to life by installing a patch of artificial grass in Carnegie Mellon’s University Center, branded #gspitt, and seeing how students used it. In documenting this via a Tumblr, he also fused this ‘feed from the future’ with contemporary tweets about green space from others.

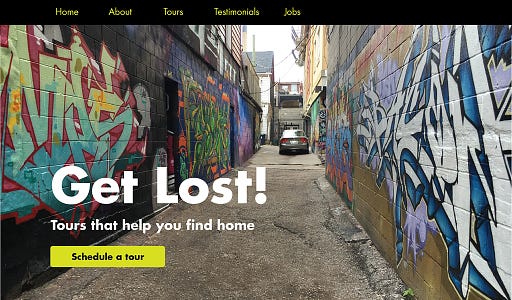

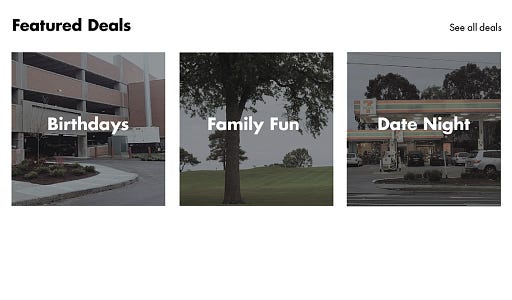

Kate Apostolou’s Get Lost! imagines a consequence of increasing detachment from place, “where people have lost their intuitive understanding of the world around them because of technology dependence”. Get Lost! is essentially dérive-as-a-service, “a speculative tourism service that reconnects people with their home environments”. Kate’s reflection on the project explores the ideas further.

Filtered realities

The mainstreaming of forms of augmented reality in 2016 was reflected in two projects looking at how its evolution might affect our everyday interactions with the world and each other, particularly the notion of its enabling of / convergence with filter bubble-type phenomena.

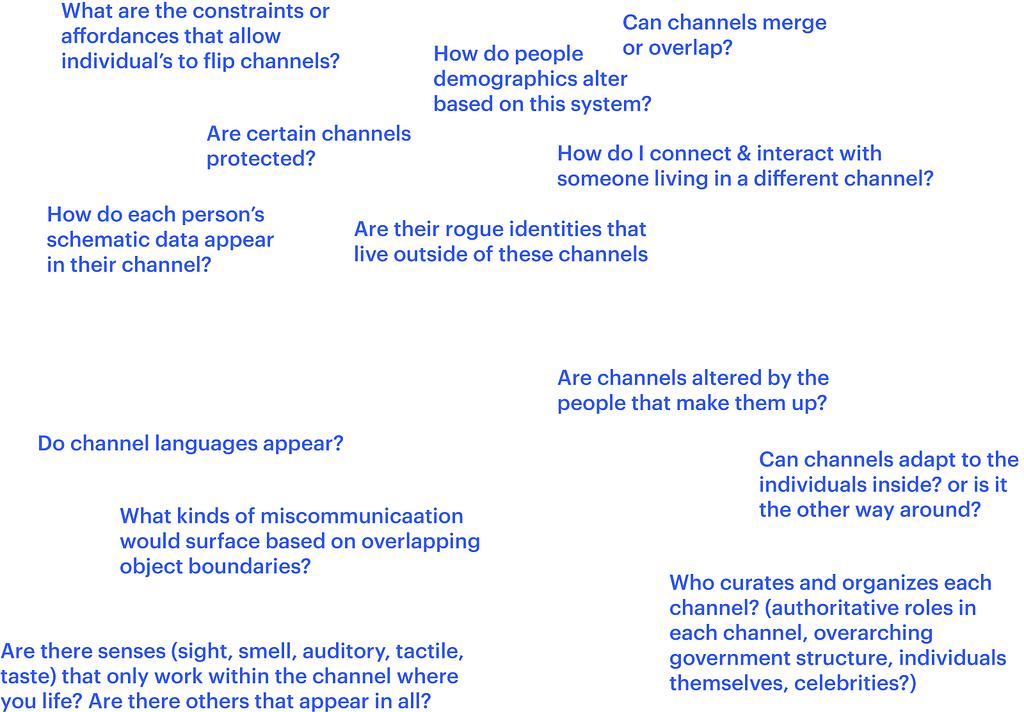

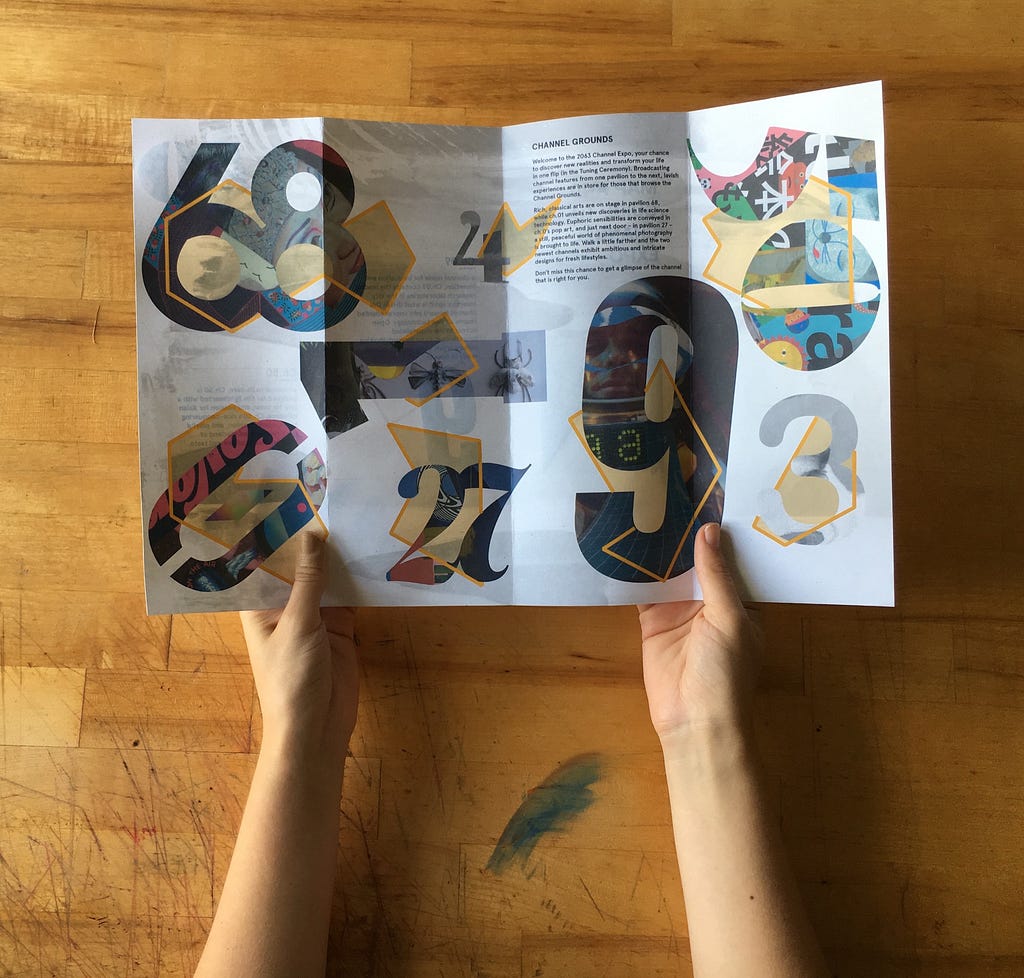

Rae Headrick imagines the 2063 Channel Expo, an event unveiling hundreds of channels of augmented reality which people can choose to tune into for the next three years—“your chance to discover new realities and transform your life in one flip (in the Tuning Ceremony).”

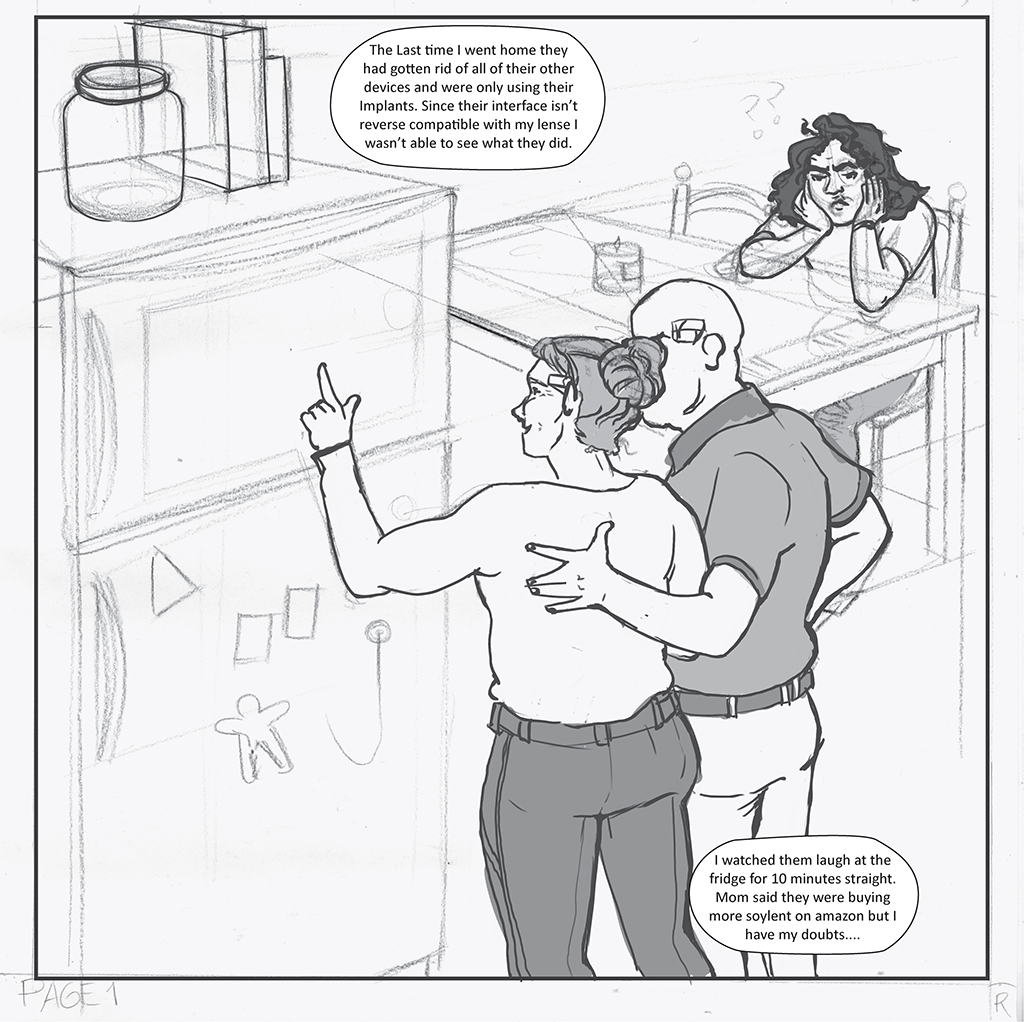

Perhaps representing a closer future, Linna Griffin’s Update is a comic exploring the issues around a teenager making the decision to have the surgery needed for an AR implant—the peer pressure, the societal norms, differences in access between wealthier and poorer families, and the history of AR evolution as taught in schools. Linna reflects on these ideas here. With other students playing different roles, Linna’s live-reading of the comic in the final Play Lab presentations was a dramatic and effective way to bring the ideas and issues to life.

Ourselves

The future of the self

How will we present ourselves to others in the future? How will we curate and re-create the ways in which others see us? Three projects examined this from different perspectives.

Zai Aliyu’s Identity Curation explores two alternatives with opposite extremes of people’s investment in curation of their identity online at levels from the individual to the communal: “In one future, identity curation is made harder through ephemerality. What if all forms of media or posted content are temporal and they have an expiry date? In the other future, identity curation is made easier through impression management. What if we can cure this sense of disconnection that results from identity curation?”. In contrast, Leah Anton’s Transpersona imagined a service which enables people to adopt ‘personas’, to “break down cultural barriers by giving users the ability to behave as if they are from another background”, particularly “to perform appropriately in professional situations such as interviews and presentations”.

Alisa Le’s Beyond the Binary looked at the future of gender expression—“how different the world would be if from the beginning humans were not raised based on these stereotypes and “norms””, via “an imaginary gift set a new parent might receive during a baby shower or a similar celebration”. Alisa also explored more questions around design’s role in perceptions and reinforcement of gender norms in society.

Dealing with death

Evolution in the way we deal with death is the focus of projects by Vivian Qiu and Rachel Chang.

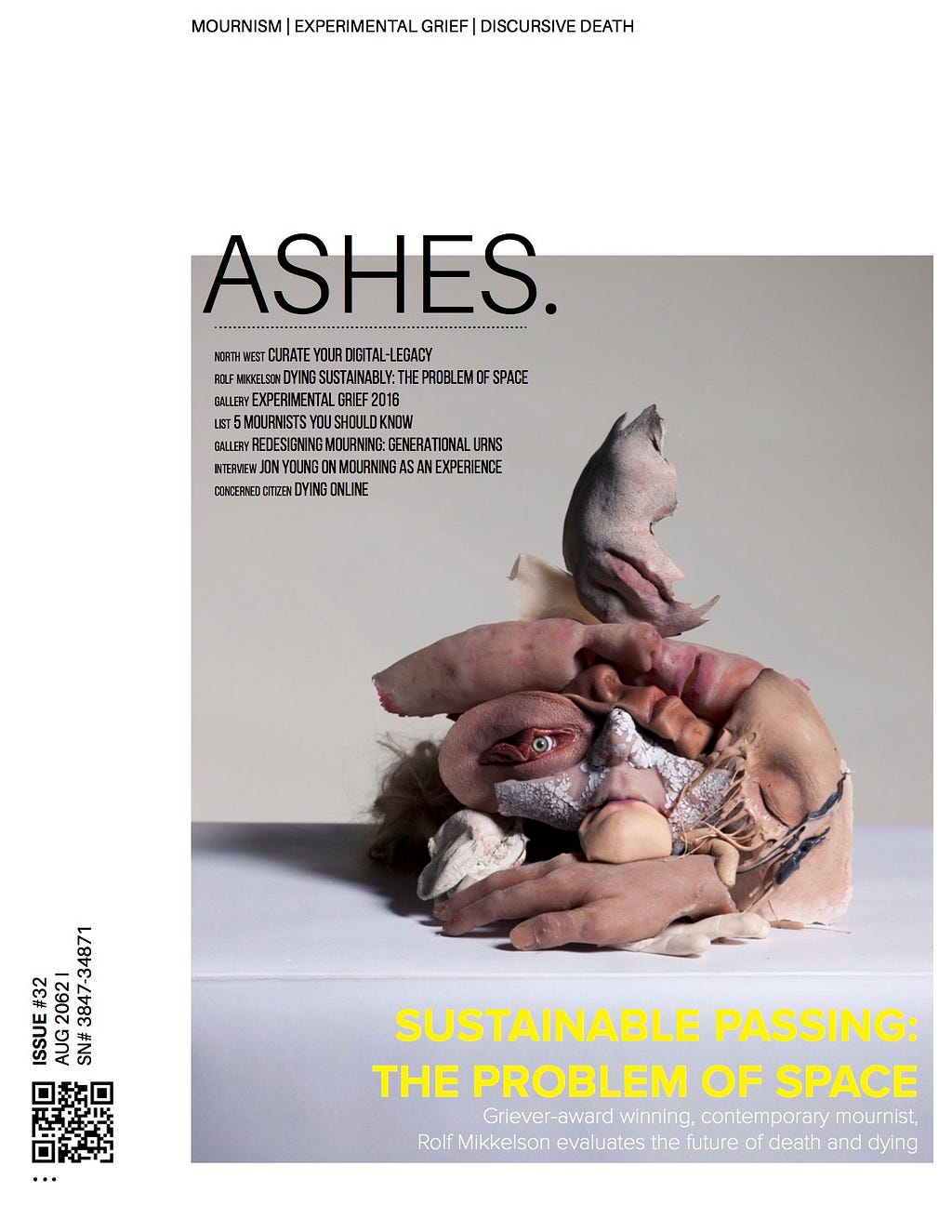

Vivian’s ASHES. is a “high brow magazine for the future elite to plan their own funeral”, imagining a world where “dying becomes a claim to individuality or a exposition of values” through articles such as ‘Curate Your Digital Legacy’ with North West, and ‘5 Mournists You Should Know’ covering ‘notable designers in the field’. Rachel’s Orpheus explores how “as a way of memorializing dead loved ones, bots built from the immense digital trail individuals leave behind become common. Preparing the bot is just another step of estate planning.” The Orpheus prototype concentrates on the touchpoints of the service, while Rachel’s reflection examines some deeper questions around artificial intelligence, design, and death.

The body as site

The relationship between our bodies and technological advances was a theme running through a number of projects, but three in particular explored this in more depth.

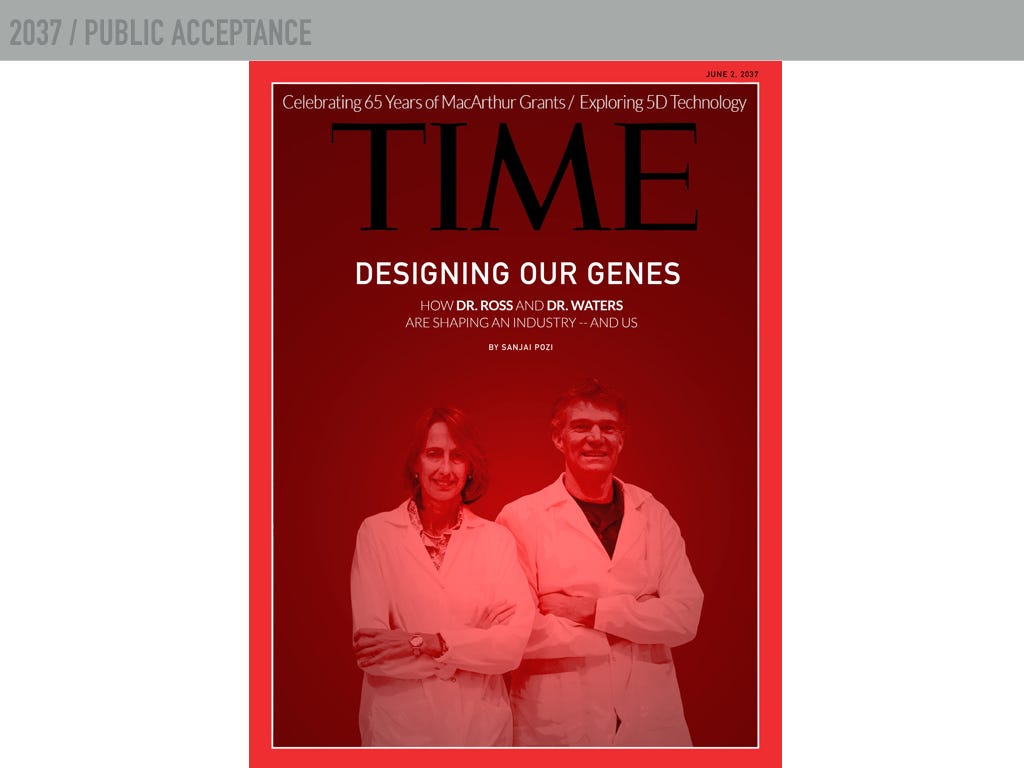

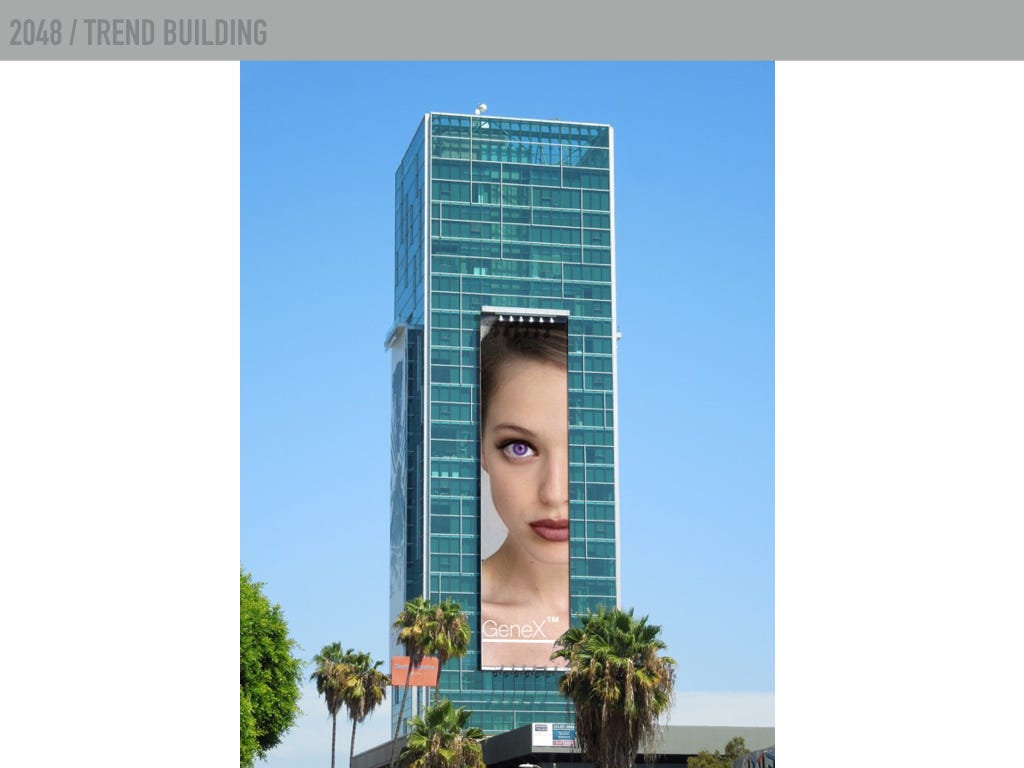

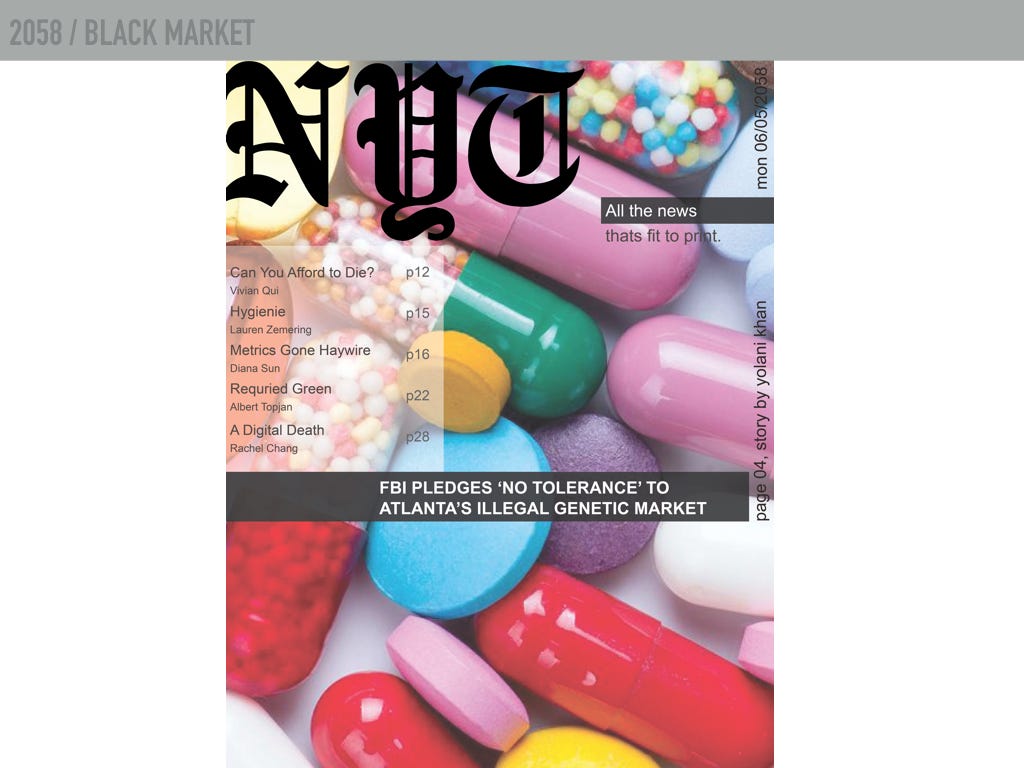

Courtney Pozzi’s Cosmetic Genetics examines the development and mainstreaming of gene therapy and genetic engineering via a projected timeline and scenes from that timeline, with newspaper and magazine headlines and covers. Building on the pattern seen in reconstructive surgery and popularized drugs, the project explores the “idea of a tipping point, or the when, what, and whys behind how an idea detrimentally splits between its utopia and dystopia, and how both of these worlds may coexist within a singular future.” Courtney explores these questions further in her reflection in relation to speculative design and ambiguity.

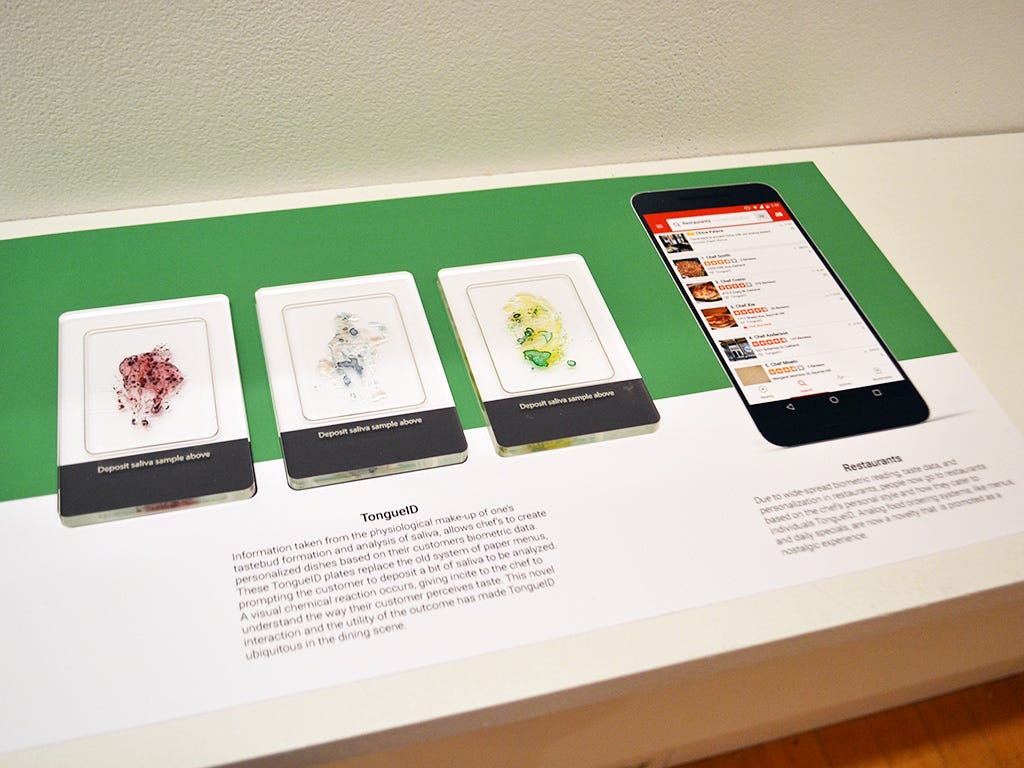

Jeffrey Houng’s A Biometric Future asks “What happens when using biometric data for hyper-personalization becomes ubiquitous?” Through a vlog, TongueID plates replacing restaurant menus and new kinds of restaurant listings, the project explores how hyper-personalization could lead to experiential echo-chambers, and some wider consequences of the use of biometrics in everyday life.

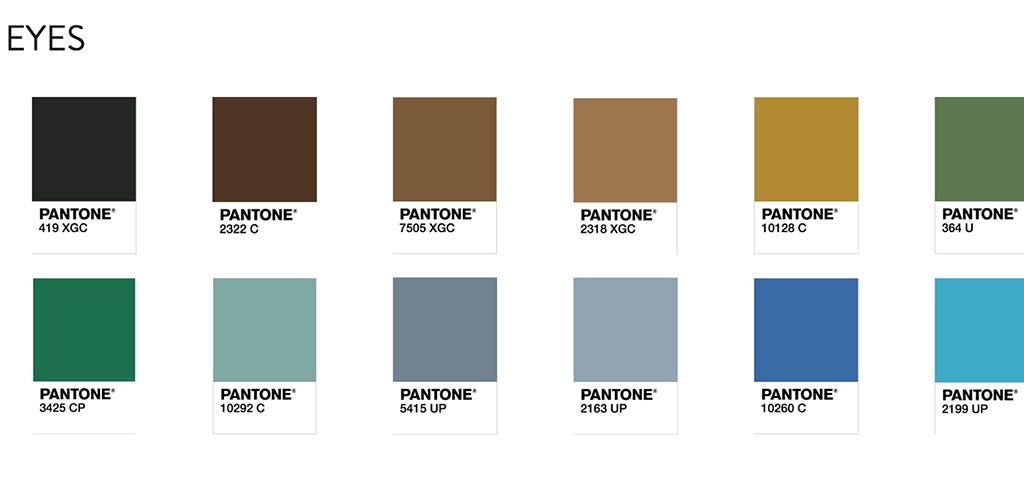

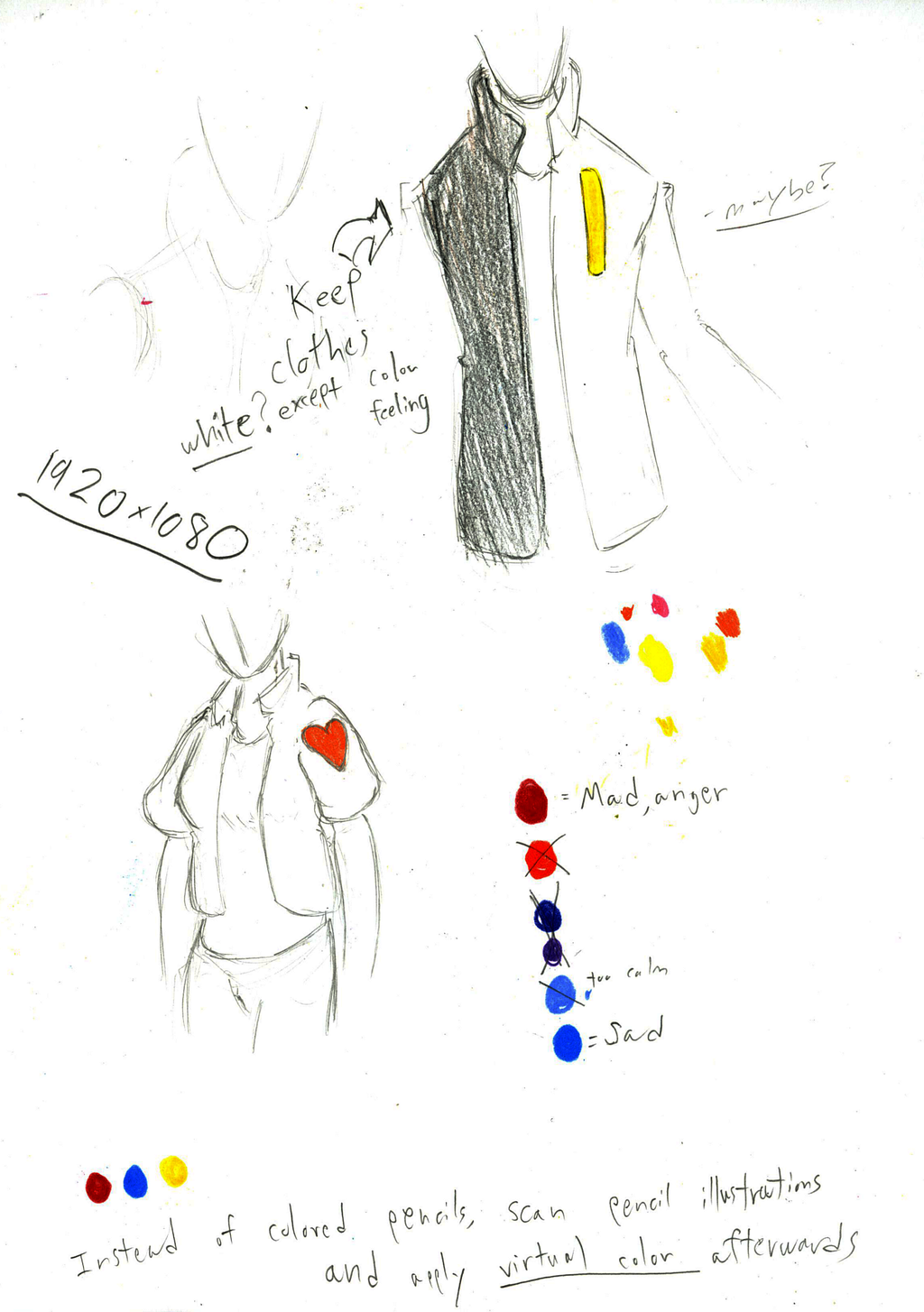

Brandon Kirkley created a story taking place in a future where “FashionTech—fashion with wearable technology that showcases one’s emotions—becomes popular”. Dealing with social interactions emerging from the visible display of emotions, and the consequences, the video “explores an everyday situation in which someone denies how they are feeling—despite what their clothes say.” Brandon also reflects on the role of the designer in relation to emotion, and the idea of such an approach making communications between humans easier.

Our communication

Voices in the head

The idea of voice interfaces, and more specifically, invisible voice technology audible only to the user, is explored, in different ways, in two projects. Ruby He’s Visual Aids in an Audio World imagines the (AR) iconography needed to accompany conversations with each other in a world “when information and interactions are almost entirely in our ears, it will be much easier for people engage in audio realms different from their immediate surroundings by playing music, listening to podcasts, etc without others even knowing.”

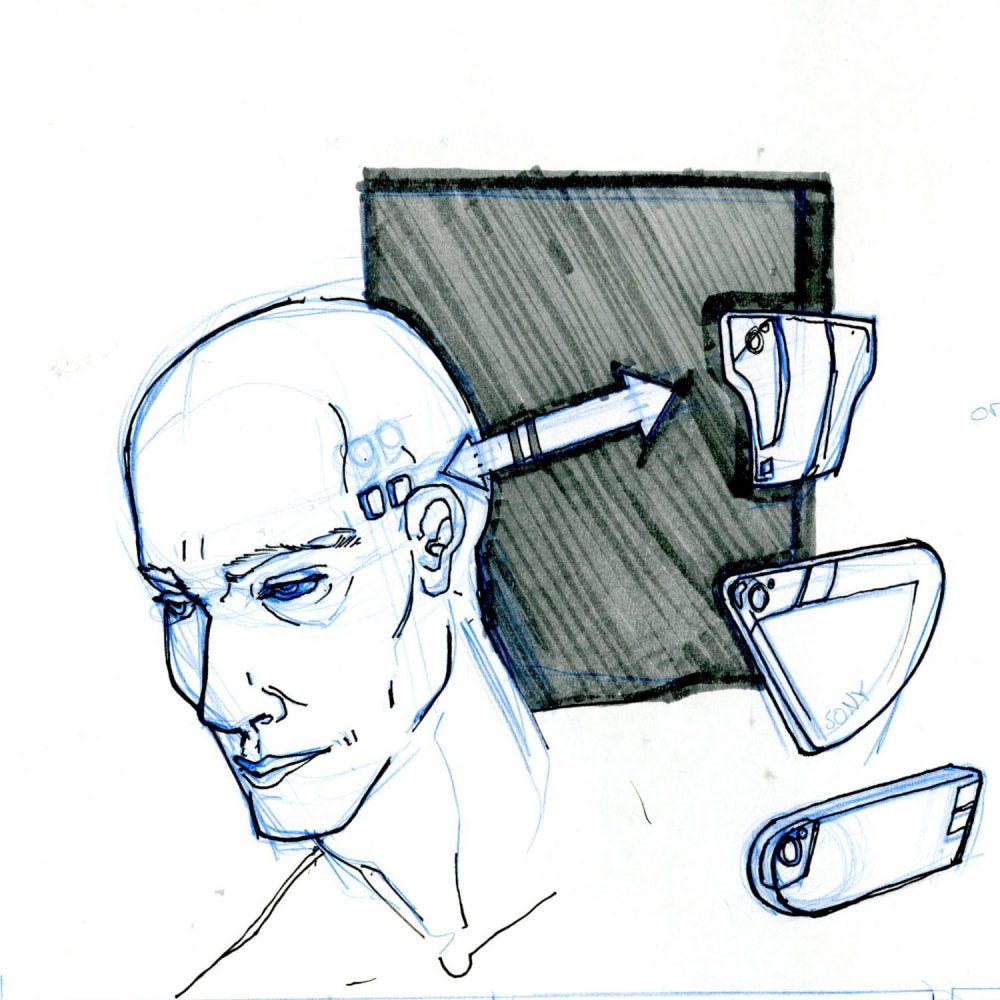

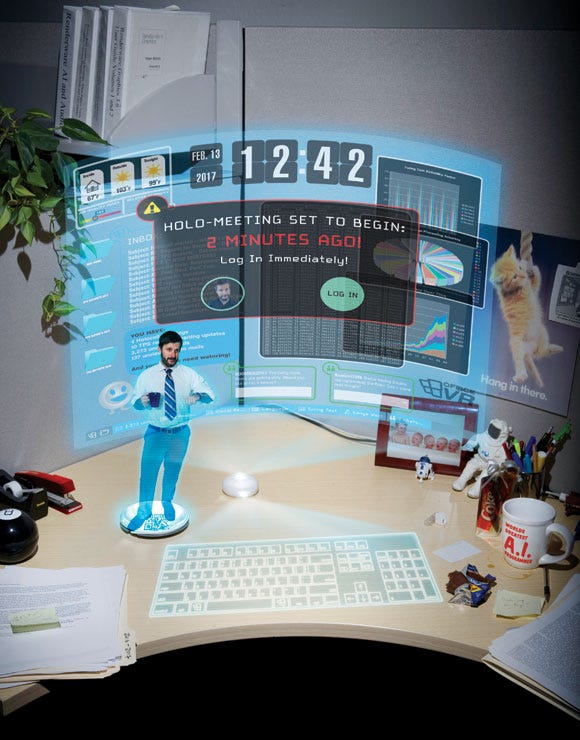

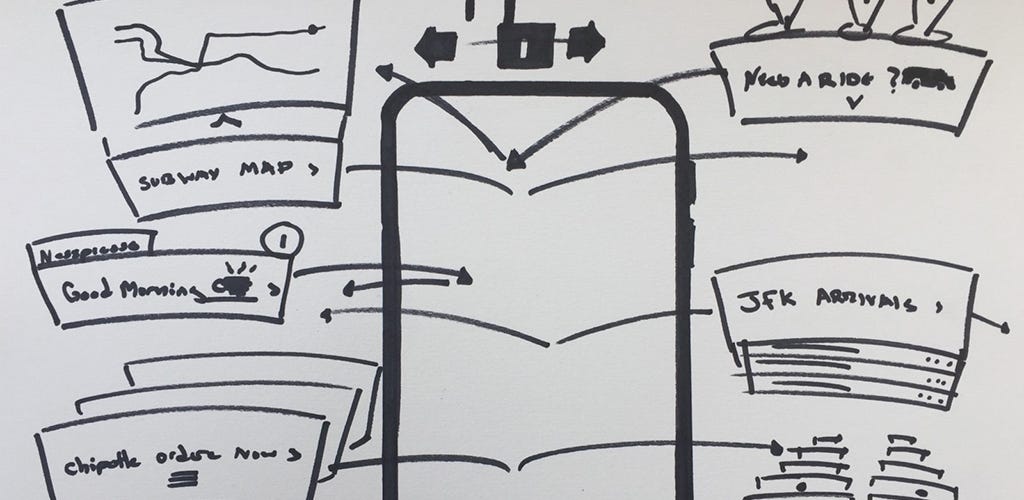

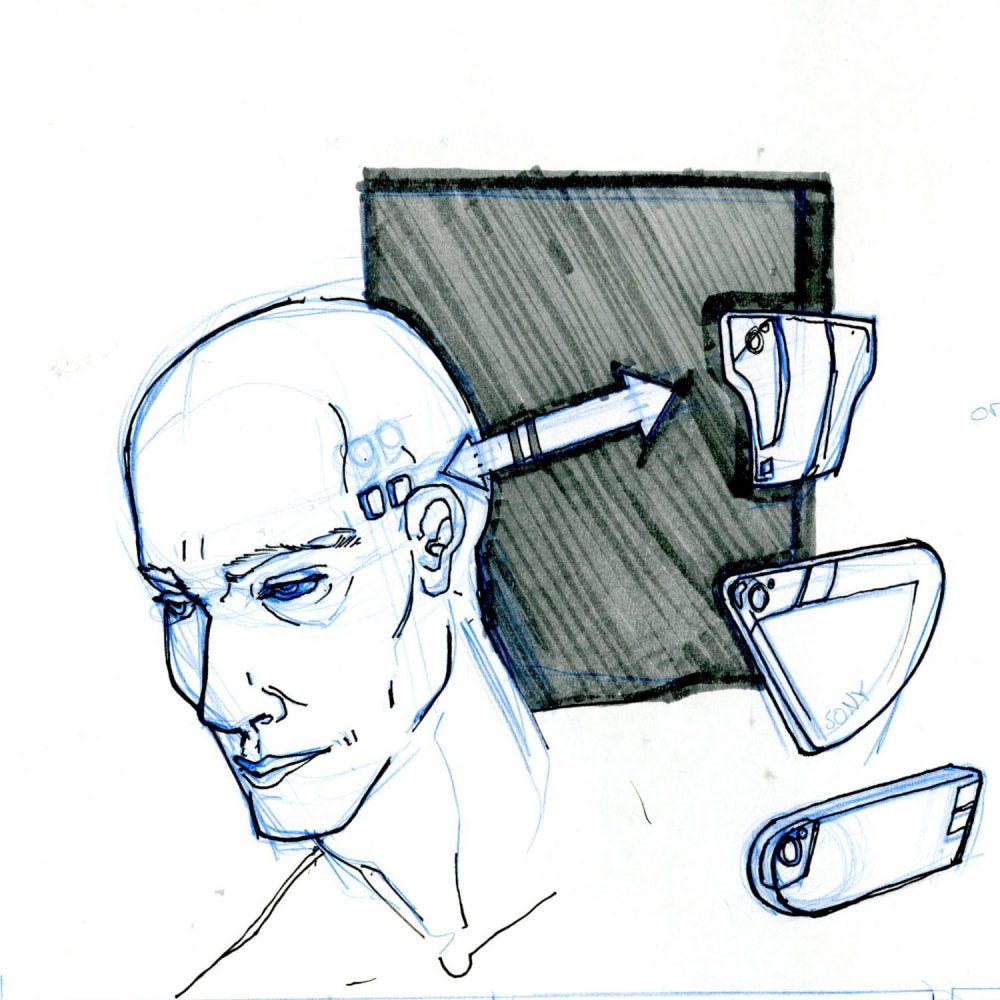

Going perhaps one step further, Zac Mau’s Future of iOS brings to life the idea that “within 50 years we will stop using phones to natively access the Cloud and digital service platforms including Facebook, Maps and Uber, and instead stream all of our digital content directly through our brains. This would result in a thought-based interface that we mentally interacted with, rather than physically”. Zac illustrates this very effectively through “a day-in-the-life kind of video, that briefly takes the audience through this future where speaking to an OS in your head is already the norm”.

Changing relationships with language

How will changes in technology affect how we talk to each other? Two projects took this question in different directions. Kaleb Crawford’s Marko V examines ‘contextual computation co-authorship’ via “a speculative fiction that explores future social media interactions at the intersection of conversational interfaces, automated text generation, and post-context-collapse. Told through four audio-vignettes, the story explores how Adrian’s use of a conversational writing assistant, Marko, amplify tensions in his social relationships with a loved one, his ego, and his friends.”

Jiyoung Ahn’s Trilingo, in contrast, imagines the evolution of a new language, CCE, which fuses vocabulary elements of Chinese and English with the formal structures of computer programming languages, to enable easier human-machine communication. The idea is that children are learning this at school, and the need exists for older generations, particularly grandparents, to learn CCE as a second language. Trilingo is an educational language learning platform aiming to bridge this gap.

Our data

Memory and privacy

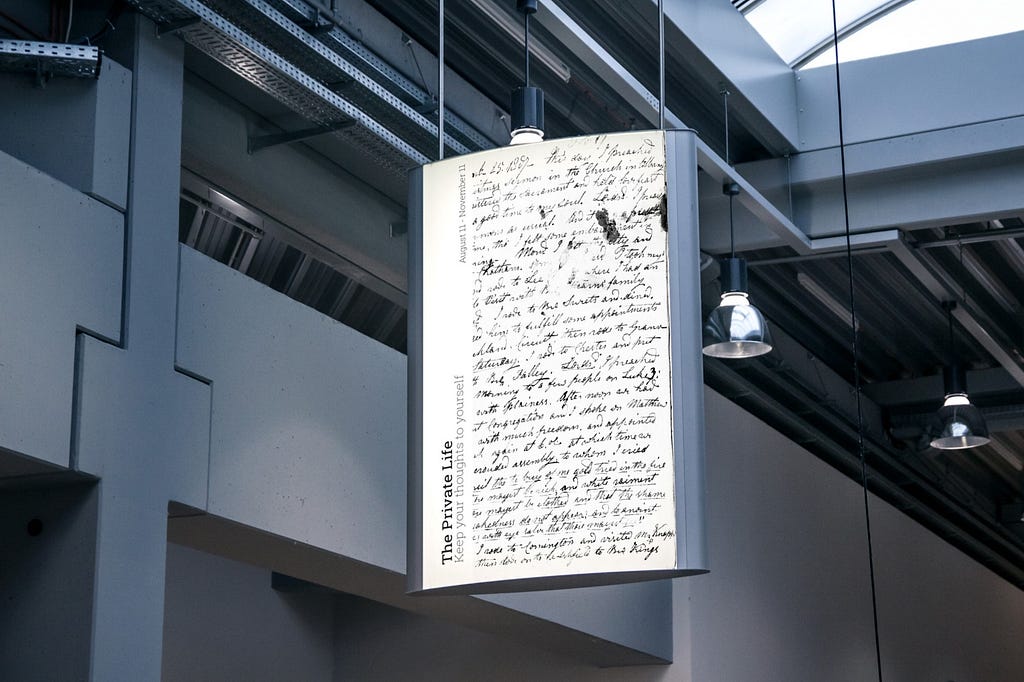

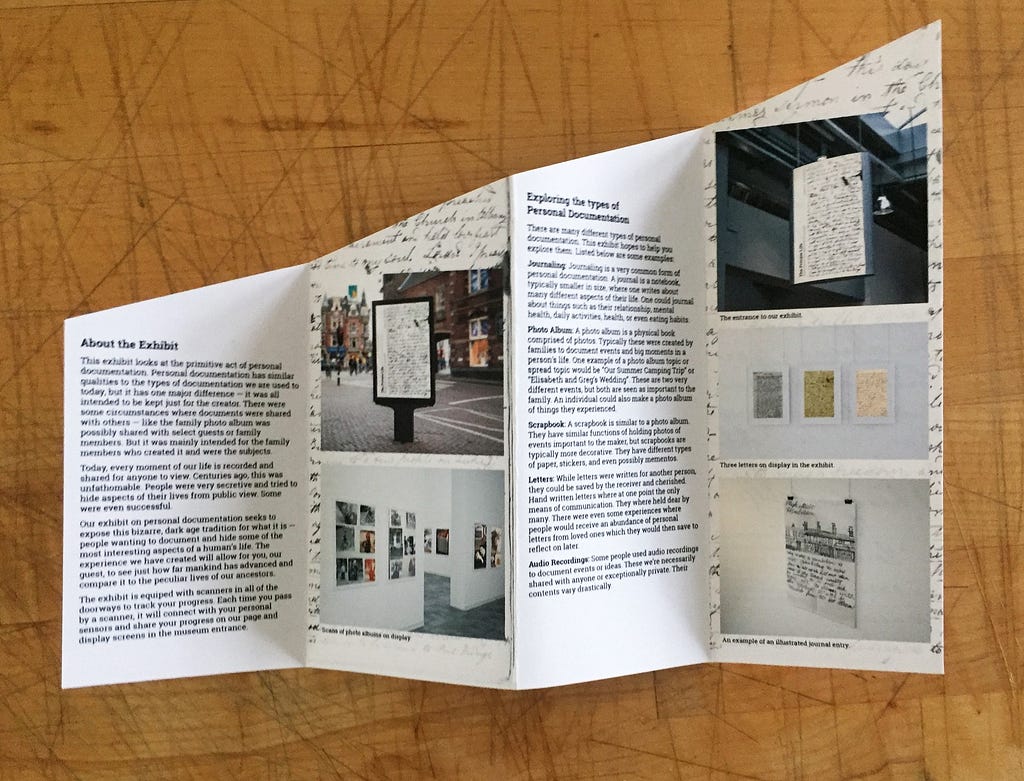

Questions around the use of data, and questions of memory and privacy, ran through three quite different projects. Kaitlin Wilkinson’s The Private Life considers a future world where privacy has been effectively abandoned—“People have become accustomed to having personal data tracked and shared at all times. This data ranges from things about health, fitness, eating habits, social habits, experiences, etc. The idea of personal information is not understood.” Kaitlin envisions a museum exhibit on personal documentation such as letters and private photos, things which “no longer play a role in the life of the average person”, complete with almost incredulous copy explaining to the public the “primitive act of personal documentation” and the “unfathomable” ways in which people “tried to hide aspects of their lives from public view”.

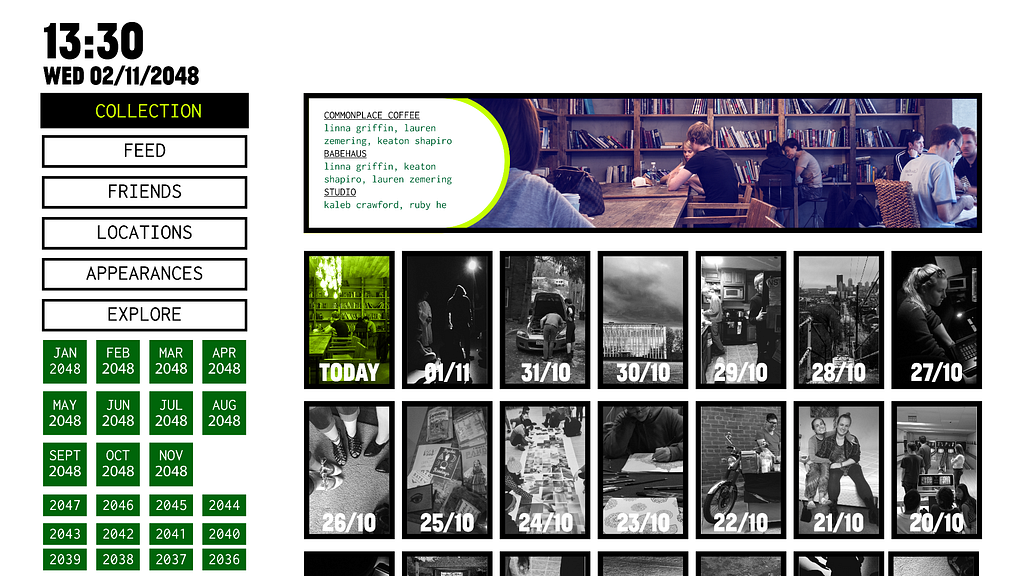

Jillian Nelson’s Lifeed extrapolates from ideas of lifelogging and sousveillance to imagine a service which “creates a catalogue of everything you see and experience in order to use it as a way to document your life story for yourself, your descendants, and for those seeking to learn about the past in the far future.” Lifeed would enable reflection and change our relationship with memory, and primarily be for people themselves rather than for sharing on social media; Jillian discusses the ideas here, including the possibility of creating ‘life documentaries’ in the present.

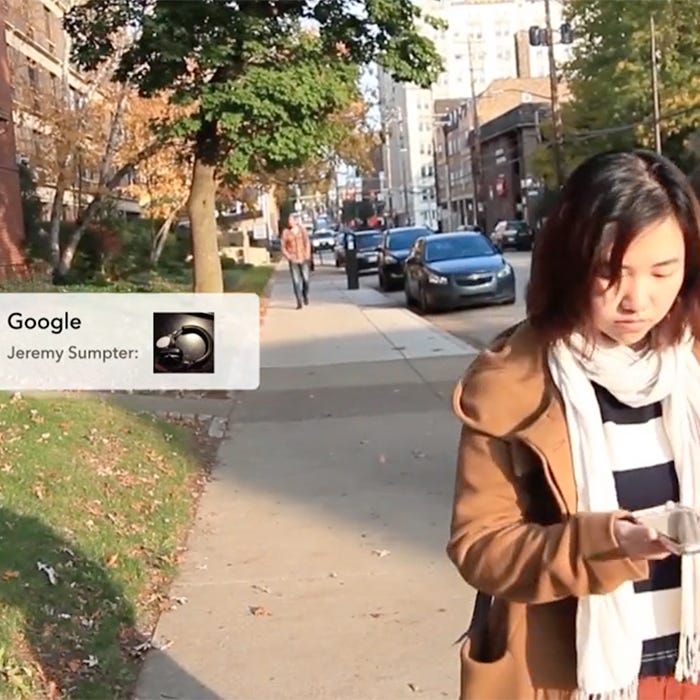

Jackie Kang envisions something closer to the present: The Future Mundane (with Google), a social evolution of Google’s search engine such that users see what others are searching for, and can follow others’ searches—friends’Â , but also celebrities’—in a form of outsourcing memory to Google and the memory of the crowd. Jackie also reflects on these ideas and the role of the designer.

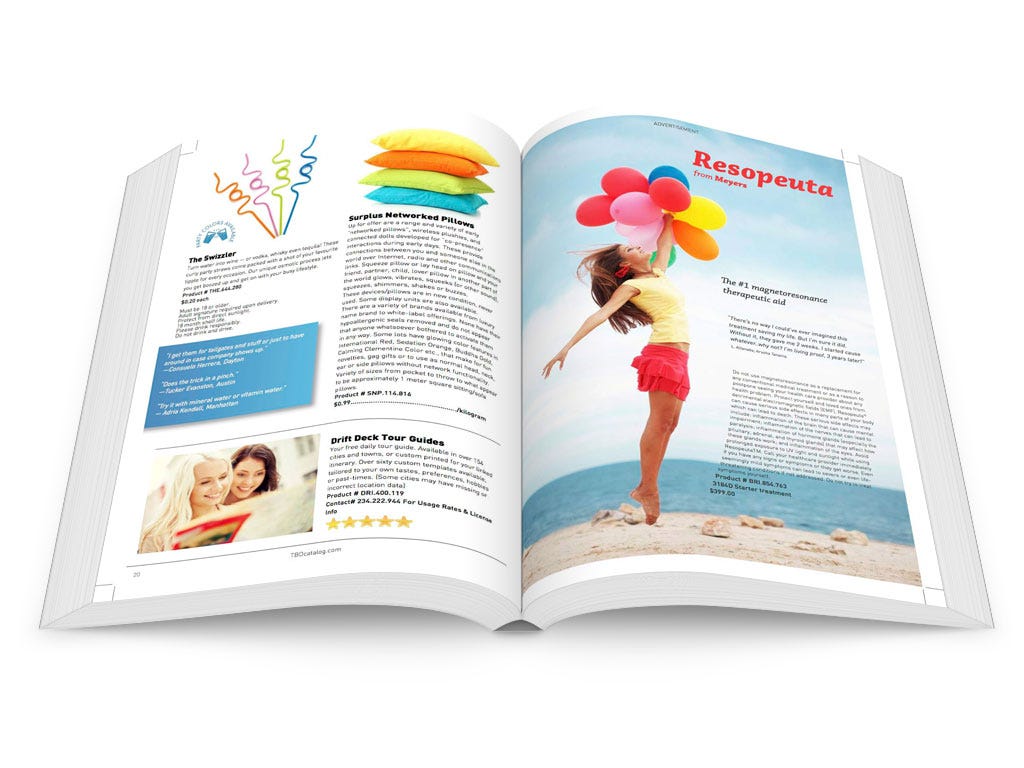

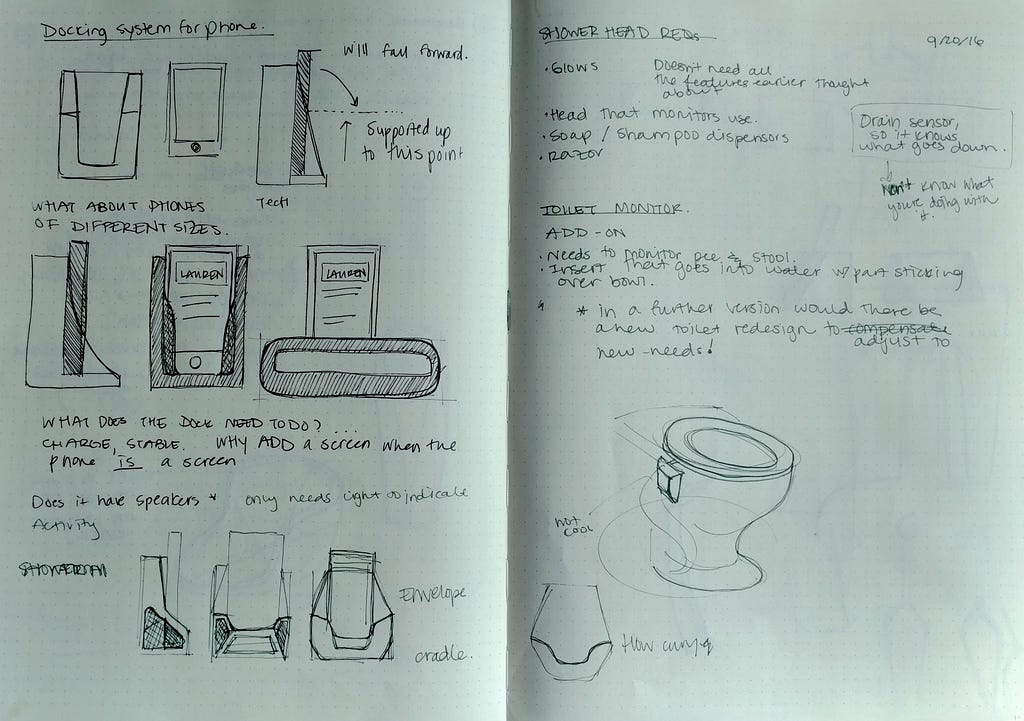

Smart everything

We saw projects earlier dealing with wider contexts of ‘smart’ homes, but two projects focused on specific product-service systems within the field. Lauren Zemering’s Hygienie is a “line of bathroom devices [that] allow users to monitor and track their shower, teeth brushing, and toilet habits. The devices not only monitor and track them, but are also able to provide feedback that can help improve a person’s health and hygiene. AND they can be awarded points and compete with their peers!” The site presents the system from the manufacturer’s point of view (including a revealing FAQ), but also shows some of the wider side-effects of the data’s use via a Google search page. Lauren reflects on these ideas here.

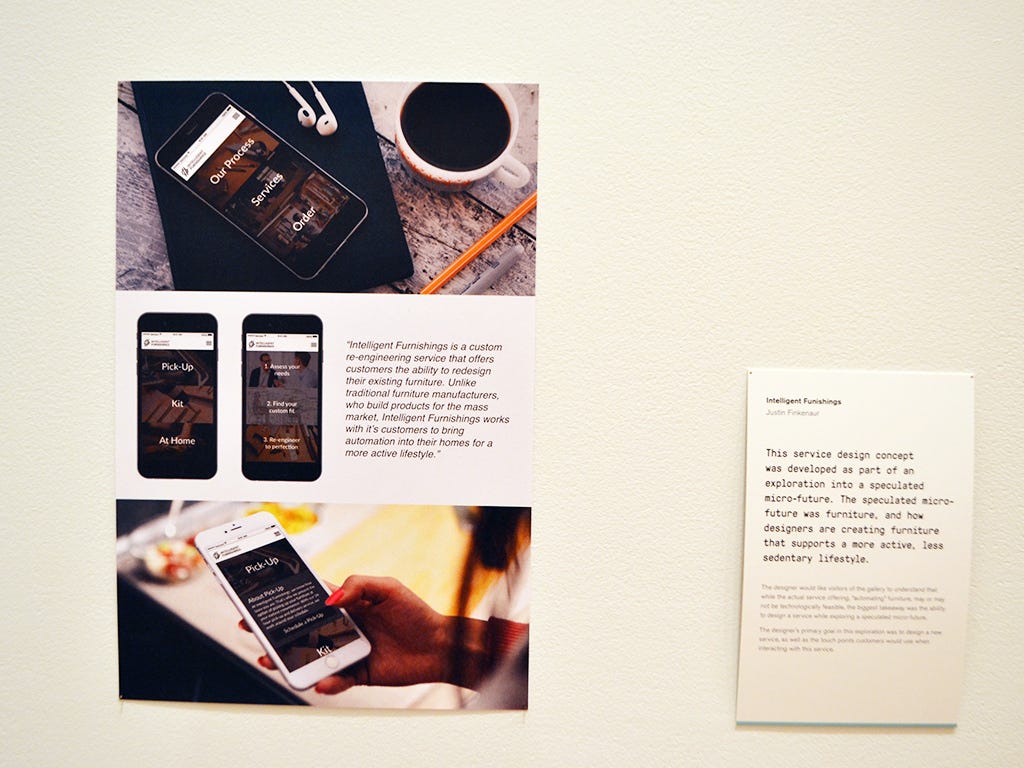

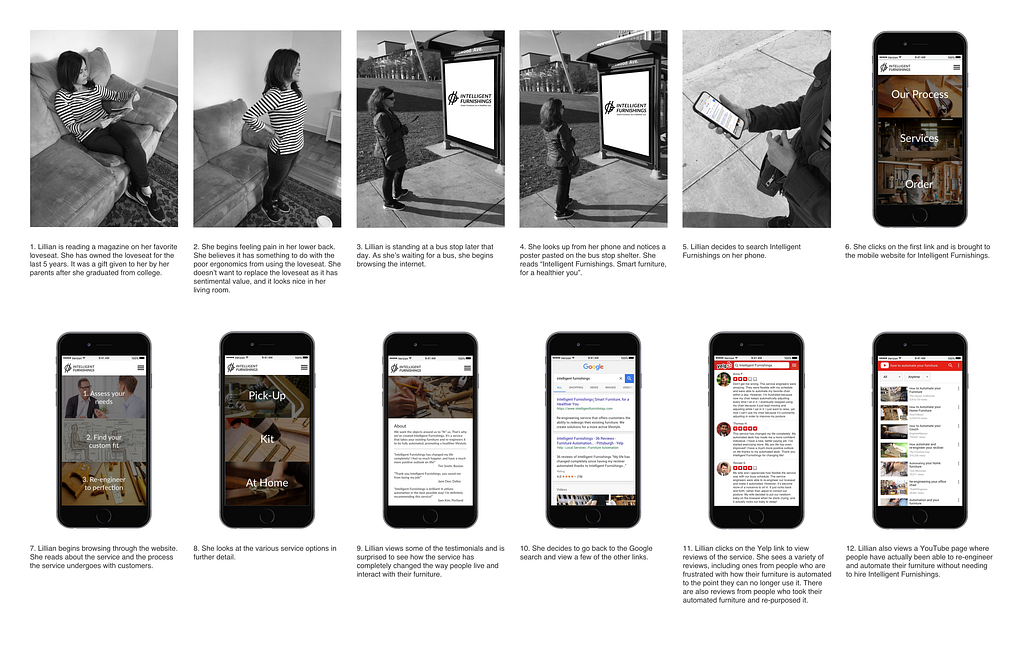

Justin Finkenaur’s Intelligent Furnishings explored the development of ‘smart’ furniture which, in response to sedentary lifestyles, involves ‘automating’ furniture so it adjusts itself to the ergonomic needs of individual people. The proposed service was explored through service blueprints, experience maps and a storyboard.

Our societies

When the millennials age

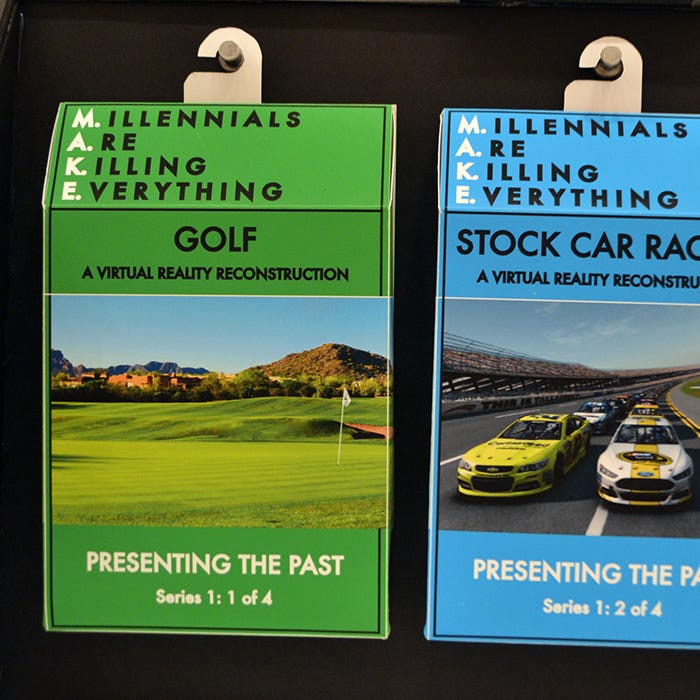

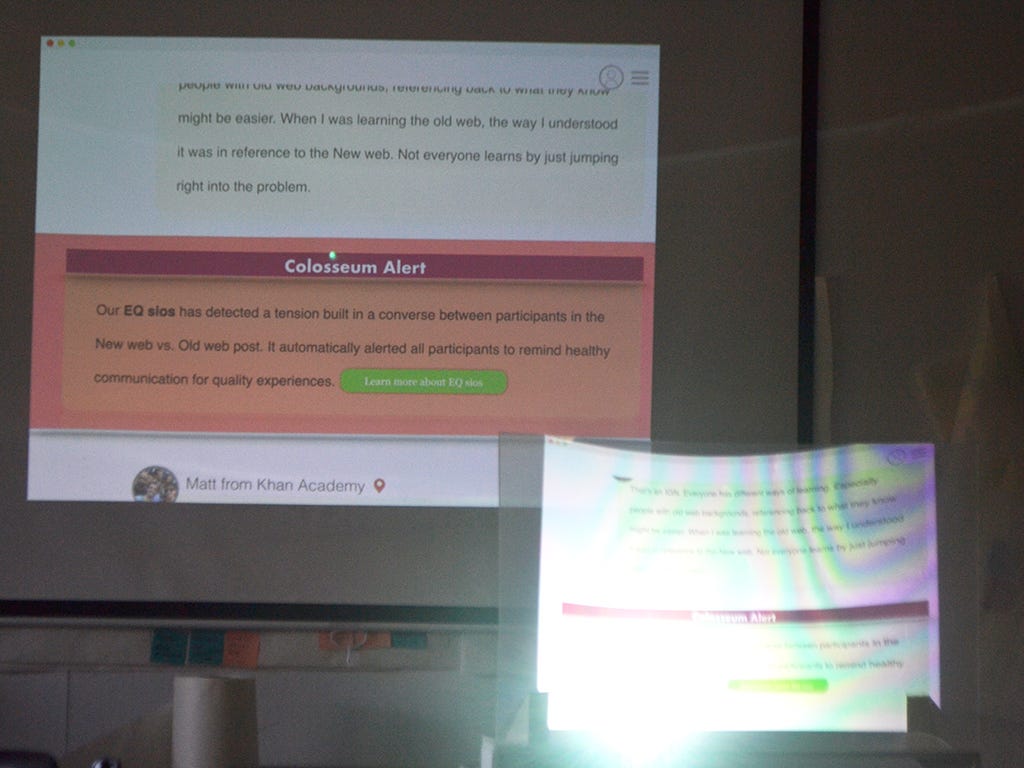

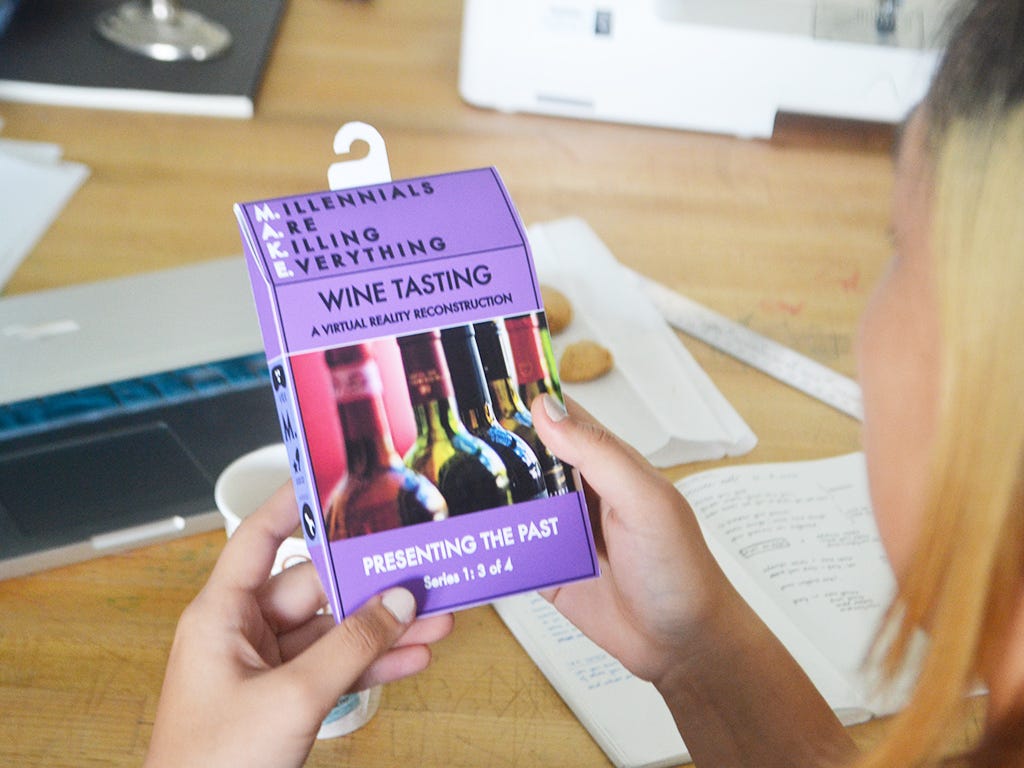

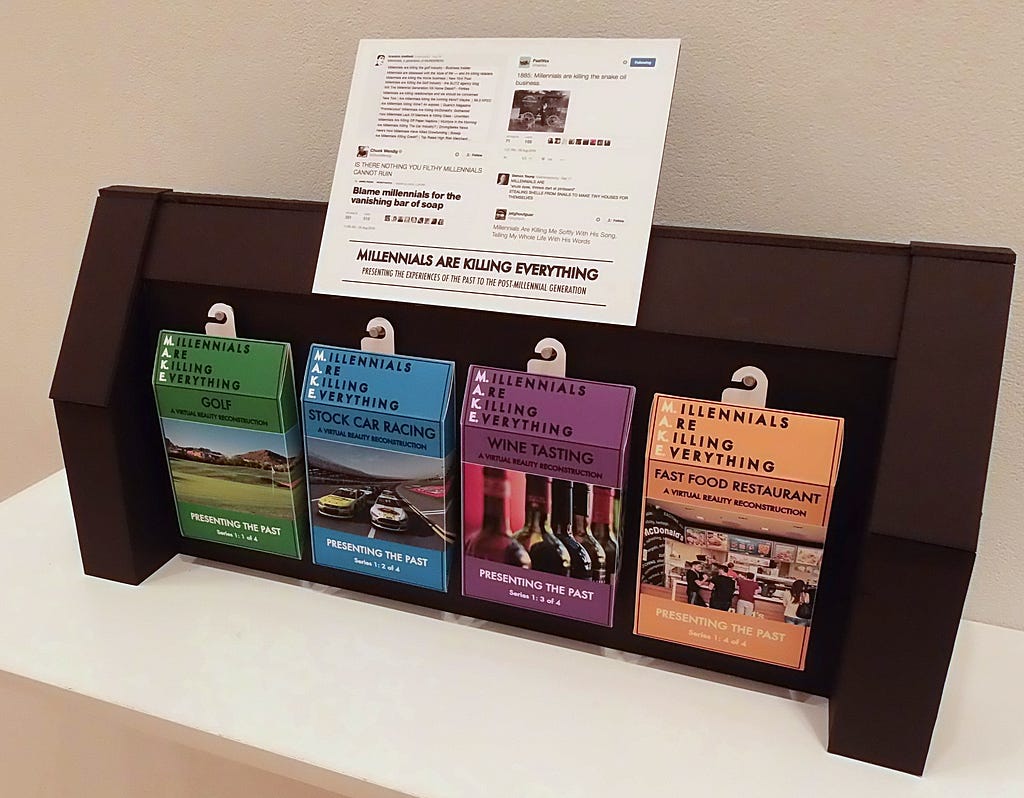

Two projects, from Vicky Hwang and Daniel Kison, deal with questions of what happens as the millennial generation ages. Vicky (forum text and a discussion of the video) imagines a disorienting experience via a forum where the ageing millennials ask for help with the ‘New Web’. Daniel takes as his starting point the current notion that “Millennials are killing everything” and imagines what vanished activities the post-millennial generations might want to ‘live’ for the first time,through a store display of virtual experiences.

Celebrity

Our relationship with celebrity, and how it might change, was the subject of projects by Praewa Suntiasvaraporn and Hannah Salinas. Hannah’s Watch The World Go By tells the story of Alexa, a vlogger, and Vicky, a ‘watcher’, who spends her day watching Alexa via screens everywhere at home and at work. The video explores the effects this has on the lives of Vicky and her friends. Hannah’s blog post shows the significant amount of work required to produce the video.

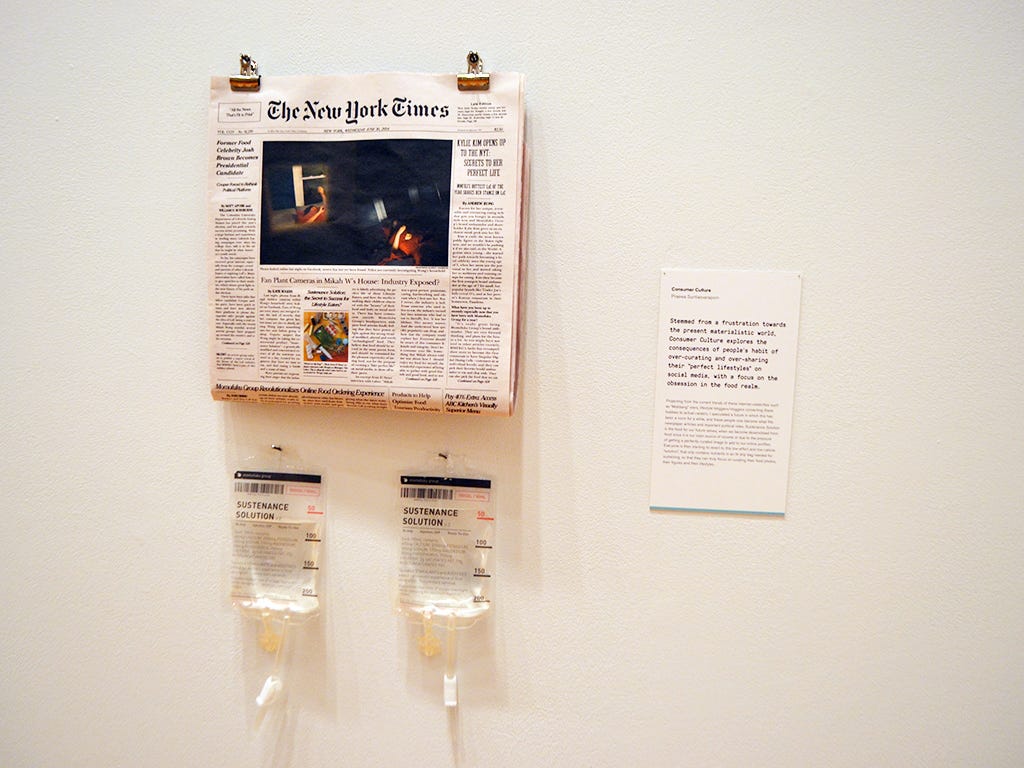

Consumer Culture, by Praewa Suntiasvaraporn, explores food celebrity, an evolution of current trends such as mok-bang and the food porn of Instagram. Praewa created a world around this, including personal artefacts from the life of food celebrity Mikah Wong, exposed through hidden cameras placed by an infatuated fan. The project examines how lifestyle eating, food presentation and photography become so significant that they dominate popular culture.

The medicalization of everything

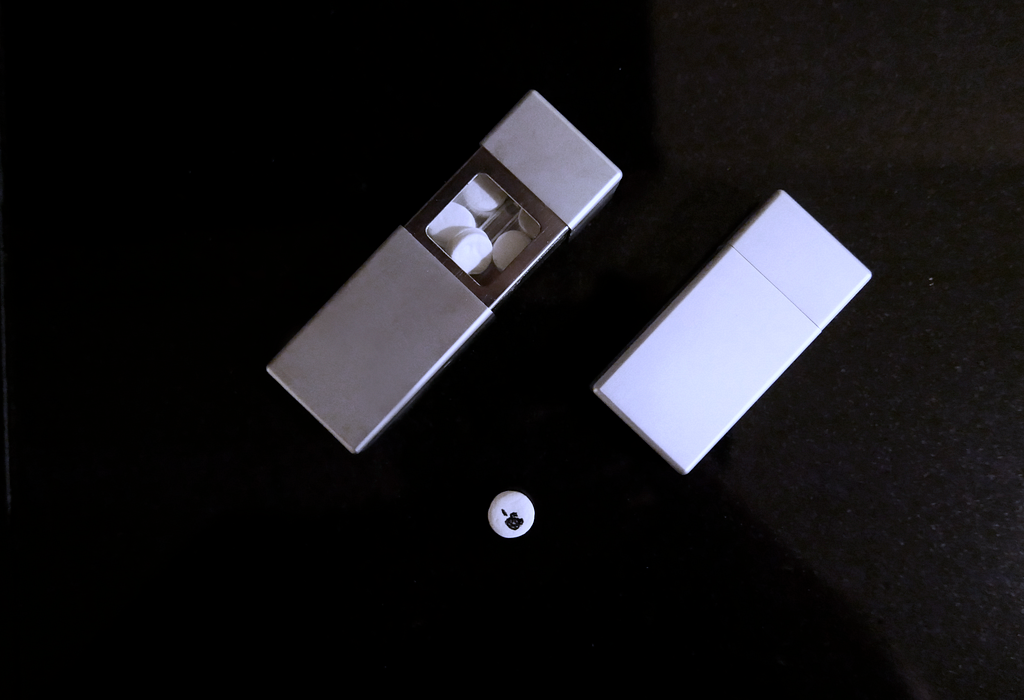

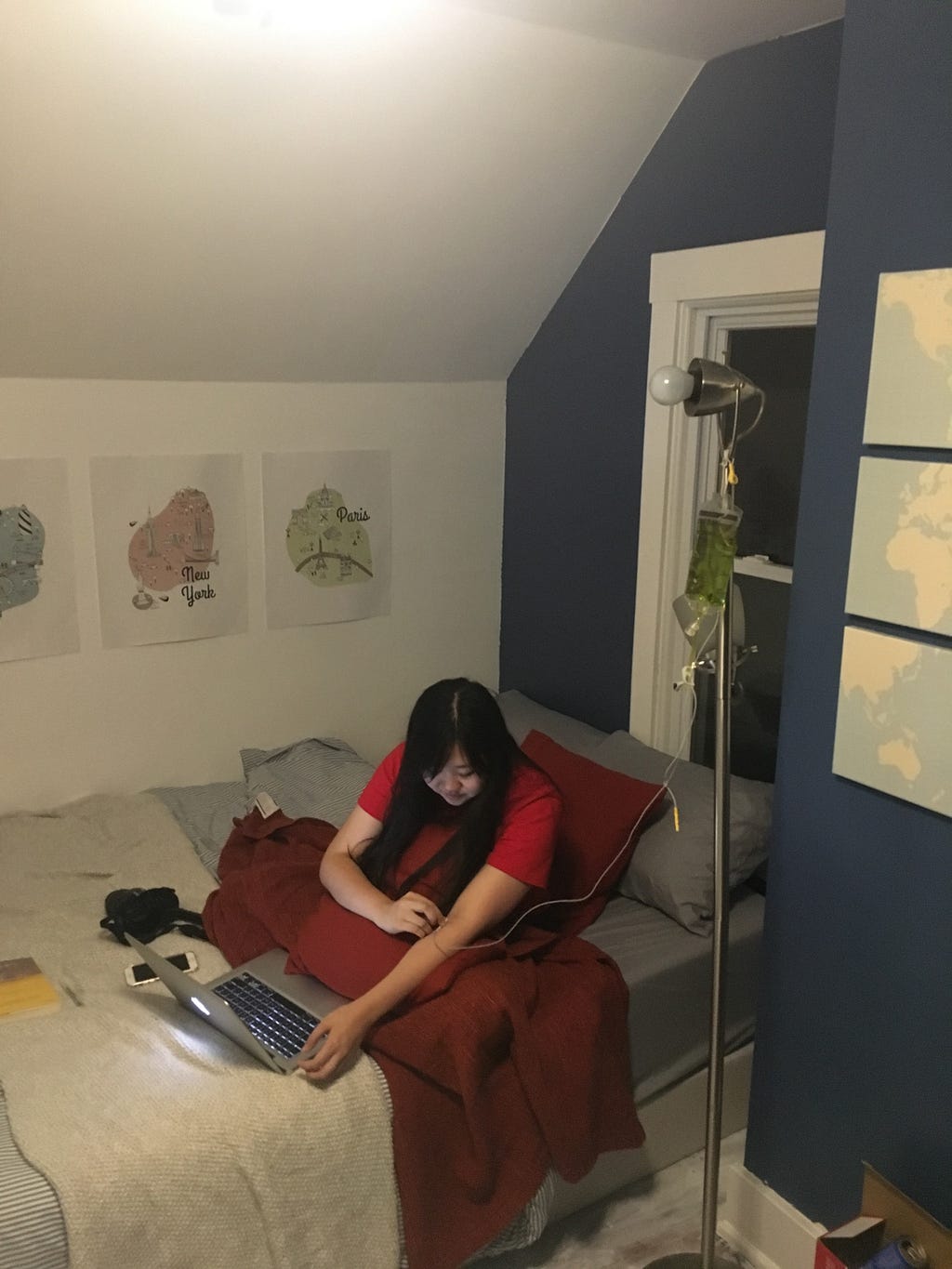

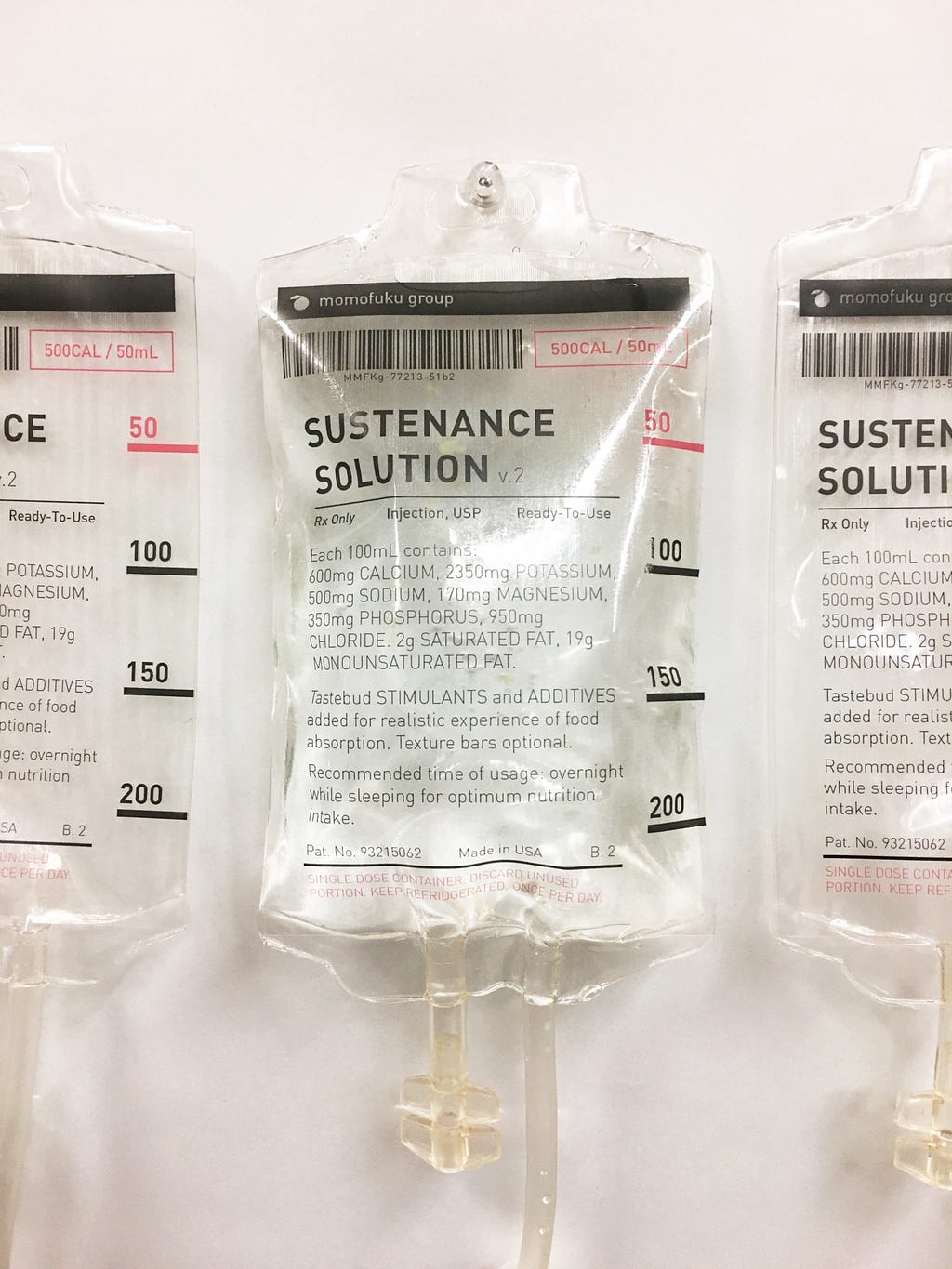

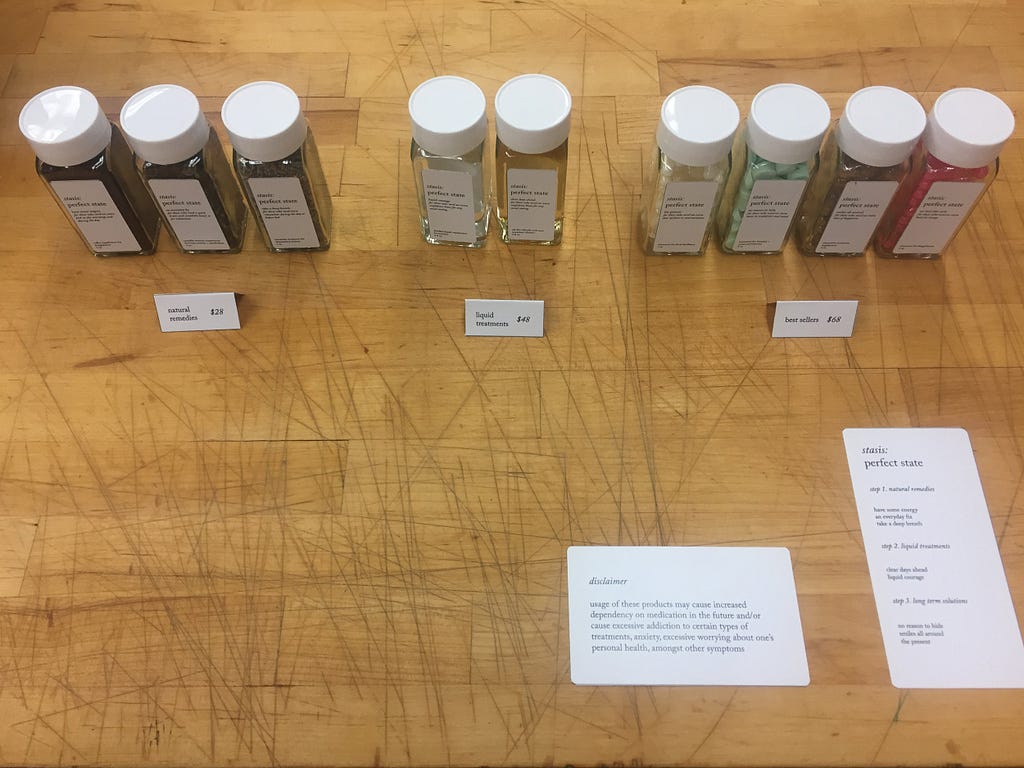

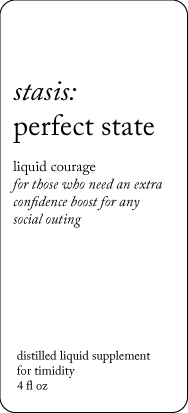

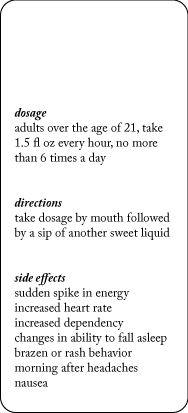

Three projects examined, in very different ways, the potential evolution of the current trend towards the ‘medicalization’ of human conditions and problems, perhaps a form of solutionism. Catherine Zheng’s Prescriptive Lifestyles is a range of medications, branded stasis: perfect state, which each target common emotions and situations such as ‘timidity’, ‘focal deficiency’ and ‘sluggishness’. In Catherine’s reflection, she notes how “No longer are people able to simply be themselves, as there is always a way to “become better”, whether that means acting, looking, thinking, or feeling the “acceptable” way.”

Jonathan Kim’s NowFood.Inc envisioned a range of ‘medicalized’ food products and consumption-related drugs such as Muse, a treatment which reduces the immediate side-effects of smoking.

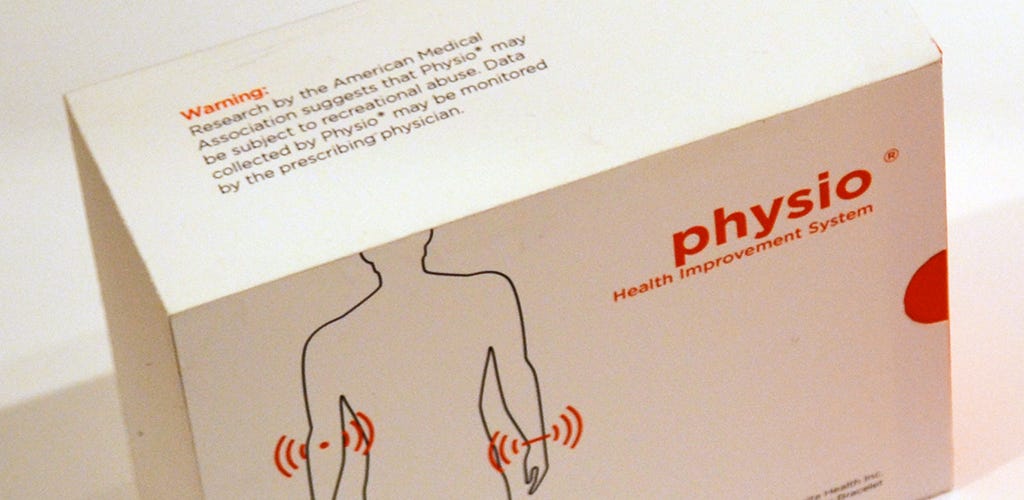

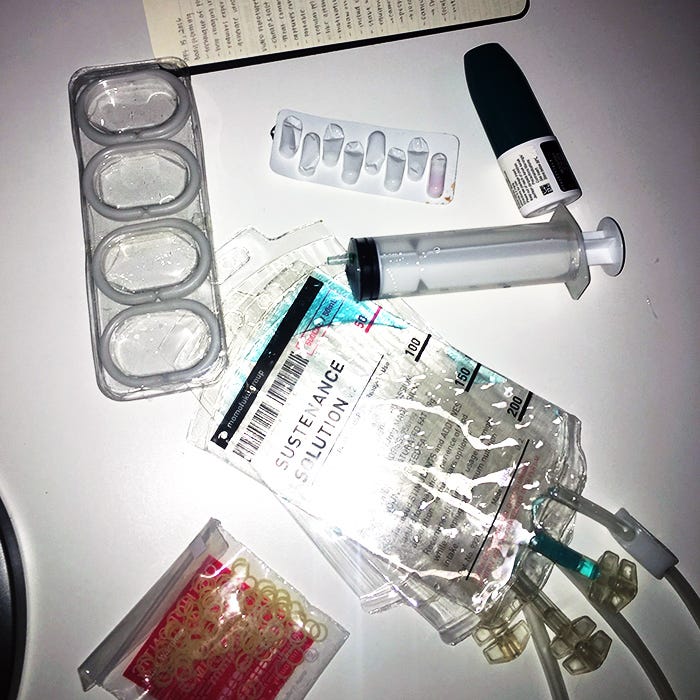

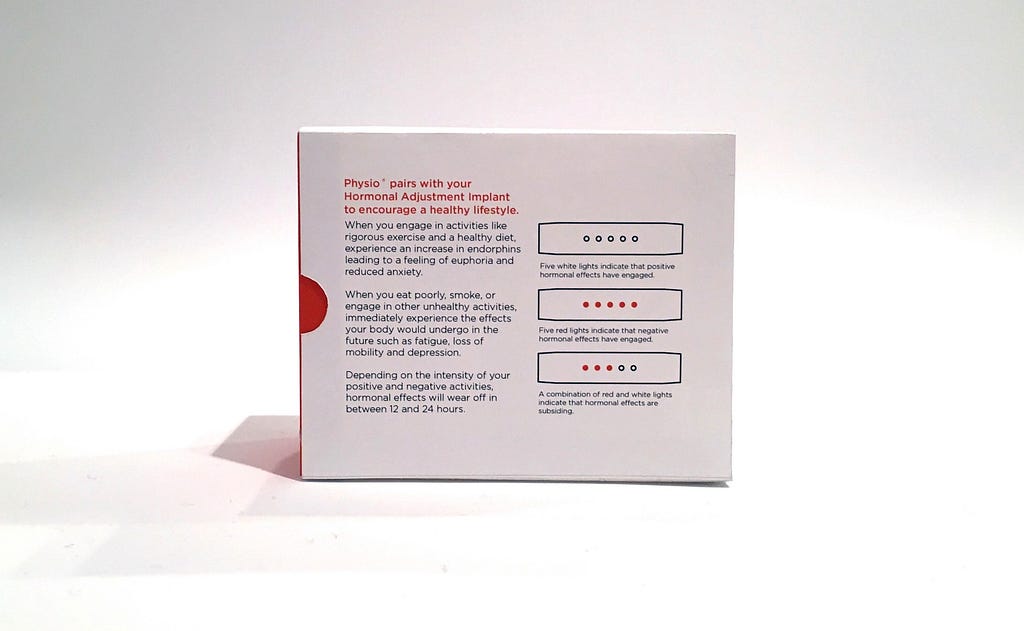

Finally, Lea Cody’s Physio is an exploration of the evolution of the fitness tracker, going beyond quantified self into the realm of actually changing behavior through operant conditioning—a “health improvement system”: “After receiving a Hormonal Adjustment Implant, the user will obtain a prescription for Physio, the external tracker. Physio will reward ‘good’ behavior like exercise with accelerated effects of increased agility, decreased anxiety, and euphoria. It will punish ‘bad’ behavior like poor diet, smoking, and lethargy with decreased agility, irritability, and depression.” Lea’s project provides an interesting example for the possibility space in design for behavior change around health, and I think could serve as a useful touchstone for this particular approach.

In her reflection, Lea suggests something which perhaps offers a succinct summary of the feelings many (not all) of the Play Lab students had about the ideas they explored:

“I believe that the role of the designer in this scenario, as in it seems all current scenarios, is to rein in the possibilities of technology to ensure a human-centered, benevolent focus.”

Final thoughts

This is the first class I have taught at Carnegie Mellon, and I was not sure what to expect. But the students have, very pleasantly, allayed any trepidation I had: they have been enthusiastic, insightful, critical and creative, and have worked very hard in short periods of time to produce the work you’ve seen on this page. I am proud of them for what they have achieved, given some very vague briefs.

What is the value of this class? I feel that being able to explore, and make ‘real’, different visions of possible futures is an important part of ‘designing agency’ and indeed Transition Design, but most importantly, to be able to think through, manage and cope with uncertainties, ambiguities and potential side-effects in a design process. If, as outlined in the introduction, Play Lab can help undergraduate design students “develop a shift in perspective on their own abilities and identities as designers”, “give them confidence to tackle new kinds of problems and challenges in a reflective way”, and help them “developing… a thought process which is not just about problem-solving, but comfortable with ambiguity, problem-finding, and problem-worrying”, then it will have succeeded. Maybe I am just teaching the class I wish I had had as an undergraduate design student, and am lucky enough to be working somewhere that gives me the freedom to do that.

The ‘critical’ in the Play Lab projects is, largely, not too critical, but it is certainly demonstrative of a curious and enquiring mindset, and, with at least a few of these projects, I think there are hints of comfort with ambiguity and contrast and the good and bad all at once, the “complicated pleasures” that Dunne and Raby speak of. Dave Wolfenden, a DDes candidate at Carnegie Mellon, is researching the notion of negative capability, a term coined by the poet John Keats to describe the state of someone “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”, and after hearing Dave speak about his research, I realize that perhaps this is what Play Lab aimed for.

The future will be at least as complex as the present, and the projects resulting from Play Lab show a recognition of that. The design fictions the students have created are, no doubt, very much rooted in the concerns they have about the world they are growing up in, and the world into which they are about to head out once they graduate (yes, in the eyes of many of the critics of speculative and critical design, most of these projects would probably, rightly, be categorized as arising from a privileged group of students with a particular mindset, and dealing primarily with people like them, but going beyond that was not the point of the class).

As Christopher Beanland phrases it (in an article on an abandoned British maglev train project, a kind of Brummie Aramis): “When you get to a certain age you realise how much more visions of the future say about the present they’re concocted in than the actual future they purport to show us hurtling towards”. Maybe what the Play Lab students have created, to draw on StanisÅ‚aw Lem, is not a collection of futures, but a set of mirrors for the present.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the students, first of all, for their enthusiasm and for giving me a wonderful welcome to CMU: Jiyoung Ahn, Rachel Chang, Rae Headrick, Jonathan Kim, Brandon Kirkley, Courtney Pozzi, Vivian Qiu, Diana Sun, Albert Topdjian, Kaitlin Wilkinson, Lauren Zemering, Leah Anton, Justin Finkenaur, Vicky Hwang, Jackie Kang, Daniel Kison, Zac Mau, Jillian Nelson, Hannah Salinas, Praewa Suntiasvaraporn, Brian Yang, Catherine Zheng, Zai Aliyu, Kate Apostolou, Lea Cody, Kaleb Crawford, Linna Griffin, Ruby He, Jeffrey Houng, Alisa Le, Gabriel Mitchell, Temple Rea, and Julia Wong; thanks too to my fellow senior design labs leaders Mark Baskinger and Michael Arnold Mages for co-ordinating and helping me get started; to Peter Scupelli for the very useful insights into previous senior design labs; to Bruce Hanington for the guest lecture for group 2; to Harriet Riley for making shah biscuits and bringing Marks & Spencer tea back from Britain for the class; to Veronica Ranner and Ahmed Ansari for lots of chats about ideas; and to Molly Wright Steenson, Stella Boess, Deepa Butoliya, Dimeji Onafuwa, Theora Kvitka, Terry Irwin, Dan Boyarski, Shruti Aditya Chowdhury, Tammar Zea-Wolfson, Robert Managad and Matthew McGehee and anyone else I have missed, who came to visit the groups’ presentations and asked some very good questions.