Last week, I put a quick survey online asking how actual designers make use of academic literature.

It provoked some interesting discussion on Twitter as well as two great blog posts from Dr Nicola Combe and Clearleft’s Andy Budd exploring different aspects of the question: ways to get access to academic research, and the frustrations of the relationship between design practice and academia. Comments on Andy’s article from Vicky Teinaki and Sebastian Deterding helped draw out some of the issues in more detail (and highlighted some of the differences between fields). Kevin Couling has also blogged from the perspective of an engineer, drawing on Nicola’s post. Steven Shorrock pointed to his work with Amy Chung and Ann Williamson addressing similar issues, much more rigorously, within human factors and ergonomics [PDF]. Someone also reminded me that I’d already blogged about related issues back in 2007.

As of now, about 50 people have filled in the survey, a mixture of digital, physical and service design practitioners: thank you everyone, and thanks too to people who emailed comments in addition.

Here’s the full spreadsheet of survey responses (Google Docs) so far. I’ve had some good suggestions for other places to publicise it, so I’ll do this in due course to get a wider scope of practitioners’ opinions.

So, what did people say?

With such a small, informal survey, I wasn’t looking for numbers, really, but rather insights and anecdotes from people’s experiences. For example, while three-quarters of respondents said they had made use of academic literature as part of their job, I suspect that is much, much higher than the rate among the designer population generally. The numbers are not going to mean that much in this context: it’s the comments which are most interesting.

The automatically generated Google Docs results hide the text comments, so I’ve extracted them (minus any personally identifiable information) at the end of this post. But in summary, the issues that emerged centred on:

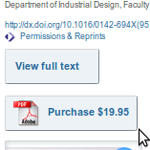

Barriers due to cost / paywall / subscription requirements

This is the most high-profile barrier, as amply covered elsewhere. One-off costs for individual articles are “usually high enough that I don’t want to pay out of pocket and it’s a pain to expense it or get clients to buy it”, and journal subscription models seem “geared toward academic institutions”. One respondent notes that “small businesses need access too and are willing to pay for it. We just need a subscription model that fits our needs.”

This is the most high-profile barrier, as amply covered elsewhere. One-off costs for individual articles are “usually high enough that I don’t want to pay out of pocket and it’s a pain to expense it or get clients to buy it”, and journal subscription models seem “geared toward academic institutions”. One respondent notes that “small businesses need access too and are willing to pay for it. We just need a subscription model that fits our needs.”

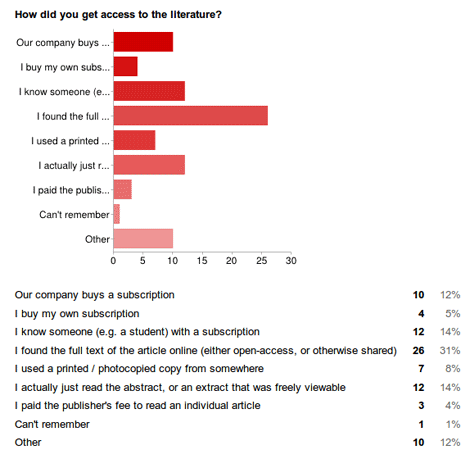

Numerically (see graph below), while a sizeable minority of respondents gained access through paying directly or via a company subscription, a lot of people also rely on ‘unofficial’ channels such as using someone else’s login or simply finding open versions of papers online (some of which may be in open access journals of course, but much of which will be self-archived ‘green’ open access versions or simply copies put online otherwise (usually against publishers’ terms and conditions). The use of abstracts (freely available) rather than reading full articles is also an interesting phenomenon. The ‘Other’ category included ‘piracy’, and getting access through university libraries as a part-time student or academic (which will often — strictly — have limits on access for commercial purposes).

Barriers due to poor search provision / overwhelmingness / not knowing where to start

Some respondents’ comments suggested a frustration with finding relevant academic research: the search tools available are not seen as being as effective as they could be; the time taken to find relevant research or the answers to questions was seen as too long; the mass of material seemed daunting; and with the addtional paywall barrier for most results, research papers cannot easily be browsed in the same way as open webpages. Automatic topic alerts were suggested as a possible answer. Much of the ‘not knowing where to start’ problem may be related to the next barrier:

Some respondents’ comments suggested a frustration with finding relevant academic research: the search tools available are not seen as being as effective as they could be; the time taken to find relevant research or the answers to questions was seen as too long; the mass of material seemed daunting; and with the addtional paywall barrier for most results, research papers cannot easily be browsed in the same way as open webpages. Automatic topic alerts were suggested as a possible answer. Much of the ‘not knowing where to start’ problem may be related to the next barrier:

Barriers due to inacessible language / jargon / presentation

Lots of respondents mentioned this, in different ways. Abstracts (often what people without access to papers have to go on) are not seen as always being written in the clearest way; papers themselves, even when people do have access, are “wordy, written in complex or academic jargon-y language” which has to be translated before they can be used. Improvements here might be about “bridging the semantic gap”, as Mia Ridge put it: “It seems absurd to say “if you’re interested in that, the secret code to unlock articles is ‘ludic’ or ‘CSCW'”.” Visuals were also mentioned: something considered particularly valuable in the design field, but which is often poorly served in academic publishing, either because journals don’t adapt their standard format to a discipline with a greater reliance on images, or because academic researchers don’t produce graphics which are up to being used directly in design processes.

Lots of respondents mentioned this, in different ways. Abstracts (often what people without access to papers have to go on) are not seen as always being written in the clearest way; papers themselves, even when people do have access, are “wordy, written in complex or academic jargon-y language” which has to be translated before they can be used. Improvements here might be about “bridging the semantic gap”, as Mia Ridge put it: “It seems absurd to say “if you’re interested in that, the secret code to unlock articles is ‘ludic’ or ‘CSCW'”.” Visuals were also mentioned: something considered particularly valuable in the design field, but which is often poorly served in academic publishing, either because journals don’t adapt their standard format to a discipline with a greater reliance on images, or because academic researchers don’t produce graphics which are up to being used directly in design processes.

Barriers due to lack of practical relevance

Some respondents commented that perceived lack of applicability to practice was a barrier to using academic research, sometimes from experience. It was noted that lab-based studies (e.g. in human-computer interaction) often lack ecological validity: they simply do not describe real-life interaction situations, and so their practical relevance has to be interpreted and considered in view of this. Some comments suggested that academic design research was not grounded in what industry needs: “It’s not tailored to a design-making audience, it seems like” — often because it is (perceived as being) slow, or even out of date before being published, covering areas which industry is already addressing. (Though one could, I’m sure, make the opposite point: that lots of academic research is covering technologies too far ahead of consumer use.) Andy’s point about design academics blogging more about their work could go some way to bridging this. The debate about whether academic research should have practical applications, or whether it should be about ‘pure’ knowledge, was touched upon on Twitter. I can see both points of view, but with design research in particular, as I’ve argued, the majority of it has some kind of practical focus driving it in one way or another.

Some respondents commented that perceived lack of applicability to practice was a barrier to using academic research, sometimes from experience. It was noted that lab-based studies (e.g. in human-computer interaction) often lack ecological validity: they simply do not describe real-life interaction situations, and so their practical relevance has to be interpreted and considered in view of this. Some comments suggested that academic design research was not grounded in what industry needs: “It’s not tailored to a design-making audience, it seems like” — often because it is (perceived as being) slow, or even out of date before being published, covering areas which industry is already addressing. (Though one could, I’m sure, make the opposite point: that lots of academic research is covering technologies too far ahead of consumer use.) Andy’s point about design academics blogging more about their work could go some way to bridging this. The debate about whether academic research should have practical applications, or whether it should be about ‘pure’ knowledge, was touched upon on Twitter. I can see both points of view, but with design research in particular, as I’ve argued, the majority of it has some kind of practical focus driving it in one way or another.

Other aspects

Now, some of these are problems and barriers perhaps specific to design (as an industry and an academic field), but others are more generally applicable across disciplines. It’s also important to recognise that these are perceived barriers: it’s easy to argue that (for example) academic research shouldn’t have to produce visuals suitable for presentation to a commercial client, but if this is a barrier perceived by a potential user of the research, it’s effectively a real barrier for that person’s company.

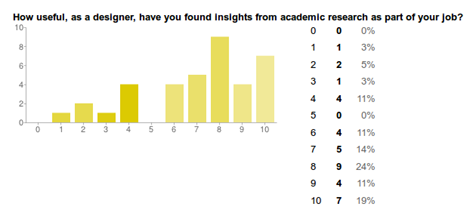

Of course, even with all these barriers highlighted, for designers who have made use of academic research, many have found it useful; the barriers in many cases seem to reflect designers’ frustration with making better use of research which they believe would be good to use. The lack of ‘5’ ratings is interesting; no fence-sitting here:

So what can be done? Introducing Concretes

I’d like to think that the tide is turning irrevocably towards open access for the outputs of academic research, but it will be some years before there’s a consistent approach which actually overcomes the barriers, perceived or otherwise, outlined above. The research might be free to access, but if practitioners find it difficult to search, and difficult to understand or apply, then the battle still isn’t won. Some design and design-related academic publications are open access already: for example the International Journal of Design — which explicitly asks authors to highlight the “Relevance to Design Practice” of articles — and Ergonomics Australia Journal (thanks to Steven Shorrock for letting me know about this).

I also suspect that as the open access movement accelerates, tools such as Google Scholar (or any number of new services) will be able to incorporate better systems for extracting relevant content from papers, aggregating relevant insights, establishing links between them, and enabling better personalised search and automatic suggestion systems.

In the meantime, what I suggest, based on insights from the survey, is that academics working in design should:

• Ensure that as many of your papers as possible are available in an open-access format, either in an institutional repository, or on your own website, and make sure that links are published enabling Google Scholar and similar services to associate the PDF / HTML version with the record it has for the publication.

• In future, when deciding on venues for publication, give more thought to publishers’ access policies, in terms of choosing open-access journals and conference proceedings wherever possible. Your department may care directly about impact factors, but having something with the potential to be more widely read will demonstrate commitment to actual real-world impact.

• Write a summary, maybe half a page, including (clear) images where appropriate, outlining the potential practical implications of every paper you produce. How would you explain it to a designer? What could a designer do with your insights? Or maybe make a video. Either way, put it in practical language. Don’t assume that everyone reading is familiar with everything you are. This is not a conventional abstract, but something designed to be useful to a practitioner. Let’s call them Concretes. See them as an integral part of writing a paper in the same way as writing the abstract. If you think your work doesn’t have practical implications, think harder. How could your theory be useful to someone actually working in design?

• Publish the Concretes, in an easy access format with automatic feed generation, every time you get a paper accepted (not when it’s actually published: do it as soon as you can, before it becomes out of date). And put a citation that people can copy and paste, at the end of the Concrete.

• Let people know about what you’re doing. You might not want to have an actual blog, use Twitter, etc, but even a blog which solely consists of the Concretes, automatically tweeted, enables so many things to be built on it. Your department could produce one which aggregates everyone’s Concretes. Go to industry conferences. Speak at them. You’ll have practice in summarising the implications of your work from producing the Concretes.

This won’t solve all of the problems, of course. And it does all depend on design academics believing that engagement with actual designers is valuable, useful, and something to aim for. It assumes that academics want people to be able to do things with their research, and place enough of a priority on that actually to take some action to make it easier. It might not be part of the metrics used by universities to assess research ‘quality’, currently, but — particularly in a subject such as design — practical impact in the real world really ought to be a goal at some level.

I’ll eat my own dog food with this, and produce a set of Concretes for my own publications — and maybe start some kind of collaborative template to enable making it easier? — over the next few weeks. It’ll be a process of matching practitioners’ needs with academics’ ability to summarise, to create a kind of loose specification for the format.

Your thoughts / suggestions / insights, readers, are very welcome.

Milton Keynes’ Concrete Cows photo (above) by Diamond Geezer on Flickr, used under a Creative Commons licence. Lab photo by brotherM on Flickr, used under a Creative Commons licence. Trinity College Dublin Library photo by A Little Coffee with my Cream and Sugar on Flickr, used under a Creative Commons licence.

Comments from the survey, in full

Designers who have made use of academic literature

• Would love to access other journals but the cost is prohibitive for a small design company. I have to get my friends who are academics to get me copies (shhhh!)

• I work in research and often look for resources around HCI topics. There are far too many search results and papers are often very close to the same topic, even citing each other. I wish there were some type of aggregator that would make it easier to get to the meat of the issue or the most relevant topic.

• I work with a ton of researchers with academic backgrounds. They are super helpful when I’m looking for literature related to my current project.

• Discussion guides or 1-page summaries (more detailed than abstracts but less intimidating than 12 pages and in more accessible language) might be helpful.

• I always want to use academic research because I feel we should be working together… but then the reality is that I usually don’t know where to go and how to find the info I need quickly. On top of that, when I do find it, it frequently doesn’t feel very relevant… Sigh! There needs to be a partnership of some kind I think to find the right balance.

• The most challenging barrier is not having access to the academic databases where academics are publishing. I have no idea how expensive subscriptions would be, but the per article price is usually high enough that I don’t want to pay out of pocket and it’s a pain to expense it or get clients to buy it.

Another barrier is the fact that I have to translate the article or paper into something my client can understand. They are wordy, written in complex or academic jargon-y language, and don’t usually have a lot of visuals. I can handle all that just fine but my clients can’t. Especially the lack of visuals.

Finally, I am someone who is interested in what the academic literature has to say, but I think there is a big contingent in design who is dismissive of anything academic. I think this is a symptom of art schools, to be honest, which sometimes leads people to adopt the old graphic artist philosophy that “if you can’t do, you teach” and other such nonsense. I am actually leaving industry to go into academia, and I’m interested in this issue. I intend to go back to industry some way and be a person who can navigate both worlds… I think that there is a real need for those types of people, people who are willing to publish in academic journals and also on industry sites, for example.• Experimental psychology is not at all practice-oriented and is hard to apply in research. Hardly anything from more ‘applied’ literature has proper psychological foundations… There’s a large gap to be bridged and I don’t know if academics are the ones to do this.

• We only have access to one database at work – which is very limiting. I do find copies of PDFs via google scholar posted in institutional repositories and by authors. It’s getting much easier to access them… But I imagine only a fraction is available in this way. You should post this survey on the ux stack exchange boards. I’m quite interested in your findings.

• Paywalls and bad writing. Very little relevance to my daily work.

• Only ever found a fully available paper freely available once. The rest of the time, you have to go on abstracts, which more often than not are not enough.

• At university and my current employer I had a subscription. Many times papers are only available under subscription; some academics tend to keep copies of their papers elsewhere, which makes Google Scholar more useful.

• In my experience academic research helps illustrate, or provide background for a design rationale, stance or methodology. However it rarely drives or dictates design outcomes. In HCI, lab research is too decontextualised for insights to be of direct applicability to practice. In academic speak its ecological validity is somewhat dubious.

• The main barrier is the pace. Often research results are flying in to late, to be relevant. The internet world has moved in between. Additionally it would help to have better summaries. As a practitioner, I’m interested in the results first, then, if I doubt them, I want to understand the motivation of the researcher and/or the methodology. But even there, a summary is enough. Keep the details stored away – give me the core.

• I really should not be costing the draconian figures it is currently costing for journal subscriptions since the publishers don’t have high costs at all, and they aren’t exactly adding highly innovative value to the work of academics. Perhaps individual universities should come together and start hosting the works of their researchers instead, instead of paying those oh so hefty fees.

• They [ACM Interactions] recently made the site easier to use and also to find articles

• For two years i teached design (service design MA course at AHO oslo) 50% and freelanced 50%. Through this combination my work gained significant input from the academic material i teaches/researched. Now that i am full time hired in a design consultancy, i miss this connection and the impact i felt it had on my work.

• Easier access to free articles. Maybe also easier to find and share with peers.

• Most relevant papers are not free and carry a substantial amount of fee. So, I ended up just reading abstracts to gauge what the paper might have said. It feels like not only judging, but also reading a book by its cover!

• depends on the job.

• I would love better alerts when new (relevant) research is available, I would like better search tools to find answers to pertinent questions we face, I would like greater (cheaper) access to these resources.

• The barriers I’ve experienced, which may be true for many, is that I am generally unfamiliar with scientific concepts expressed as mathematical equations (and those concepts that have direct relation to them). The service that I would like to create to resolve this issue (hopefully) would be aesthetic and coherent visualizations/sonifications of the data and concepts. I am working on designing a network model to give academics, artists, and anyone who may be interested open source access to these images,sounds and accompanying texts with control enabled to selected groups of users to manipulate and add to the works.

• Practical knowledge lacks at times.

• Some academic research is incredibly useful: it’s provided frameworks and insights that I’ve been able to build on in industry work. It doesn’t have to be practical, good theory is just as useful. Some, from an industry perspective, is stating the bleeding obvious. I’ve been to CHI twice and Ubicomp once. CHI has nuggets, Ubicomp was a terrible circle jerk of the usual suspects. No-one was remotely interested in talking to my colleague and I because we weren’t academics.

• Another thing is presentation. I’m comfortable reading academic HCI papers as I come from a social science background, but some are still terribly dry and poorly written. Many of my design-educated colleagues find this much more challenging (just as I find many things difficult which they do with ease). But academics need to reach this audience for their knowledge to be used. I’m not suggesting they dumb it down, but some of them really need to learn to write more clearly and many are terrible presenters. The standard academic presentation structure is a problem here as much as poor training and uncharismatic style and there’s clearly pressure to conform; I overheard lots of moaning at Ubicomp about one presenter who’d done more than just read out bullet points presentation ‘trying to be Steve Jobs’.

• Cost of access is a massive issue of course: I know where to look and still can’t afford anything that’s not on Google Scholar or ACM DLib. For many designers simply knowing where to look, and even thinking to look in the first place, are enormous barriers. If there was an expectation that they’d find something interesting and easily digestible, I’m sure more would look.

• In short, designers need to work a bit harder to look, but we need open access and more academics need to learn to do what you do, and make their research accessible to a broad audience.

• I chose very useful above but there’s scarce amount of articles available. I do find it strange that in my little team we’ll give a lot of weight to a blog post and not bother to unpick it or spend time verifying what it’s saying. I really think time and accessibility would be two key things – and by time I mean at least write the summary in plain English.

• I have no idea how to get access to further academic research. Open access would be fantastic.

• I usually consult someone in the field and ask for articles. I occasionally pay for this as well and get a list of articles to review usually in the applied anthropology space. Key wording would be helpful, it is still hard to find things even in the age of google.

• There needs to be more of a connect between academic research and design practice. Academic theories are not practical and should be made relevant to practice – written in plain english

• It’s extremely time-consuming to find relevant articles, and I just don’t have enough time on most of my projects. Access is also a huge issue. I don’t have a subscription at my current company (it’s a small place), and very few articles are published for free online. I would pay for some if I knew they would be worthwhile, but it’s often difficult to tell this strictly from their abstracts. I would love professionals to collate key academic articles somewhere so it’s easy to find the most relevant papers when starting a new project. Anything that could save me time would be incredibly helpful.

• Places like JStor just need better and clearer subscription models. They seemed to be geared toward academic institutions. Small businesses need access too and are willing to pay for it. We just need a subscription model that fits our needs.

Designers who haven’t made use of academic literature

• The industry regularly shares and publishes its findings for free in magazines, on blogs and at conferences. In contrast academics only publish in sanctioned journals read and accessable only to other academics purely because of the “academic credit” they receive rather than through a genuine desire to educate and share.

• Papers and similar are a waste of time. Academics should be blogging and getting interviewed in mainstream media / sites.

• I usually don’t even go down the route of looking at academic research because I assume it won’t be (a) as up to date as thinking I can find elsewhere and (b) it’s not a regular resource I can ask my company to look into accessing. It’s not tailored to a design-making audience, it seems like.

• Academicians and researchers do their studies to reflect a difference in the way we think, to radically look at the conditions. If the access gets easier, we would probably cut the chase, and test and implement ideas much more efficiently; in the benefit of the society.

• Industry doesn’t know about research and even if it did a great deal of it is not directly relevant or applicable at the coal face

Pingback: Från Abstracts till Concretes | Erik Stattin är här

Pingback: Designers, literature, abstracts and Concretes | Architectures | Dan Lockton | Entornos virtuales, creación de contenidos de autor y su evaluación | Scoop.it

Pingback: Outside the Matrix: Dan Lockton | :InDecision: